First thing you need to know (if you don't already): Kara Walker is a rock star.

Tickets to a recent talk between Walker and Selma director Ava DuVernay at Los Angeles' Broad Museum sold out in a matter of hours. Hundreds of people waited in long lines to see her massive (75 feet long!) mammy-sphinx sculpture, "A Subtlety: Or the Marvelous Sugar Baby," made entirely of white sugar and installed in the old Domino factory in New York, every day that the installation was open. Dozens of people also protested the work, insisting that the sphinx's full lips, flat nose and do-rag – not to mention the surrounding small black boys, made of unrefined brown sugar – were, in the words of SUNY-Old Westbury black literature professor Nicholas Powers, "re-creating the very racism this art is supposed to critique."

Tempers flare around Walker's work, and they have since she first burst onto the scene in 1994 with "Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart." (She has a penchant for incredibly long titles – there wasn't room for the entire title of "A Subtlety" above – but they are integral to understanding her aims.) For many years she focused on large cut-paper silhouettes, or works playing with the idea of silhouette – magic lantern projections, shadow puppets – but even in her recent public art installations, Walker continues to probe the wounds of slavery, racism and sexism. With furious intent, Walker uses the stereotypes of "Negritude" to attack the violence visited upon black bodies/female bodies/black female bodies, forcing viewers to confront the past. She couldn't be more imperative if she took your chin in her hand and dragged you physically to face the wall, and no doubt it's this imperious stance that has won her as many detractors as fans.

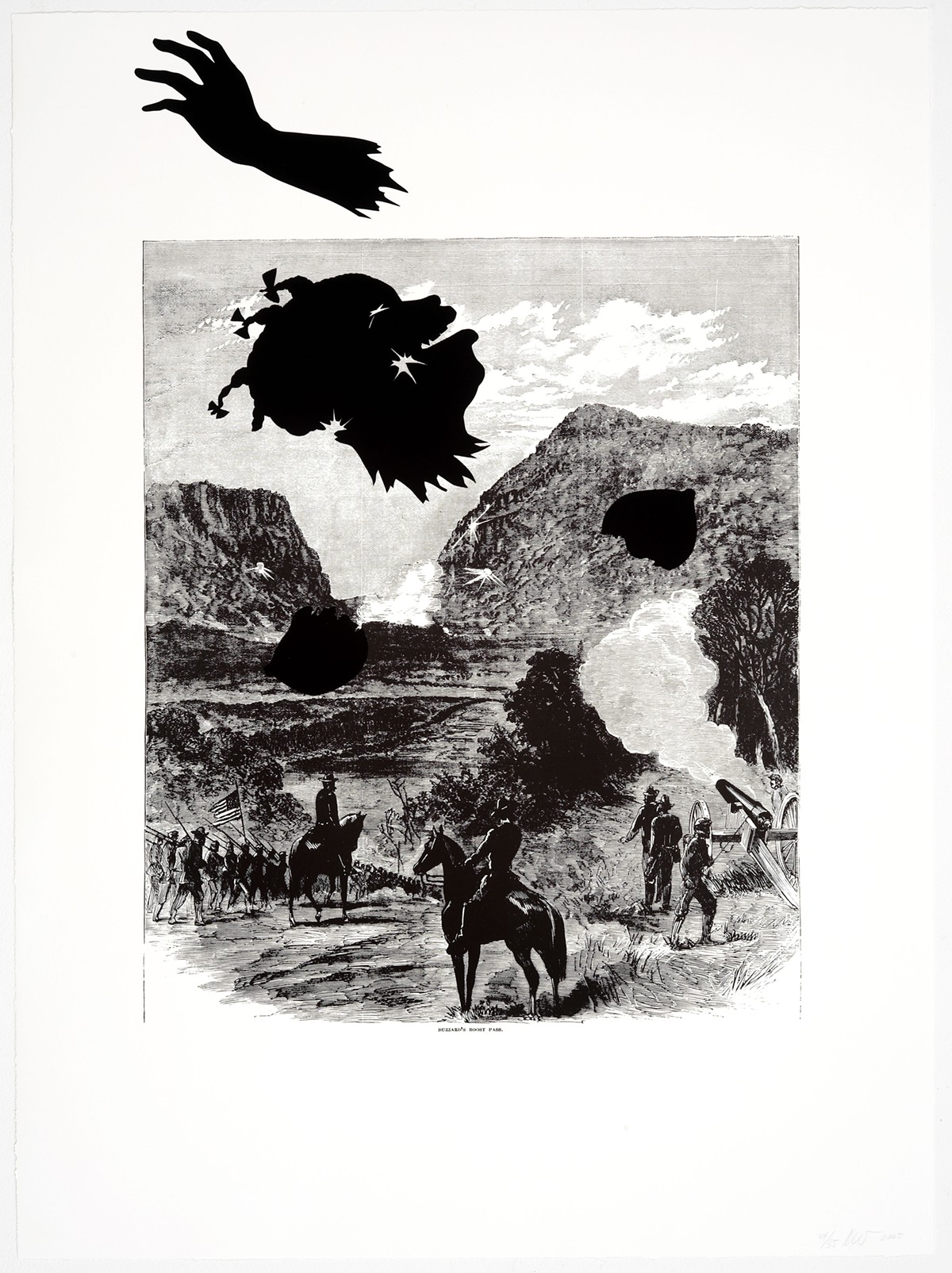

The same force simmers in the series of prints currently hanging at the Cornell, though it's somewhat easier to overlook – at first. Walker's "annotations" consist of her silhouettes overlaid upon a series of quaint woodcuts published by Harper's in 1866, purporting to tell the facts of the Civil War in pretty pictures. These obvious fairy tales are demolished by Walker's interventions.

To walk among these mammoth prints is to feel the weight of history pressing in on you. Walker's silhouettes, silkscreened over offset lithographs from the original plates, weave in and around the stock-heroic Union and Confederate soldiers, utterly negating their puffed-up self-importance with the brutal truth of shot-up faces and severed limbs. While mustachioed men in uniform wave their sabers, caricatured African figures toil in fields, flee through forests, die mutilated. Viewers may recoil from the viciousness of those caricatures, but their power is undeniable.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Walker compared her distortions to Zora Neale Hurston's use of Negro dialect. "There's always this question: 'Is she using language in a way that is demeaning to black people? Is it a throwback for her to be using colloquial Southern speech? Is it capitulating to the demand of white audiences who want to hear black people in a particular way? Or is it speaking her truth? And is that allowed as a black artist? Are we allowed to be individuals within this sea? Or do we have to be unified in this collective?'" Walker reclaims the power such stereotypes have to harm by exaggerating it and thrusting it in the viewer's face.

The portfolio of 15 prints was donated to the museum by Barbara and Ted Alfond, as part of the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art that has energized the Cornell in the past year, and the exhibit was curated by a class of Rollins students led by CFAM curator Amy Galpin. Sunday is your last chance to see these icons of intersectionality up close, and for anyone who grew up in a once-Confederate state, that's a highly recommended experience. No joke.