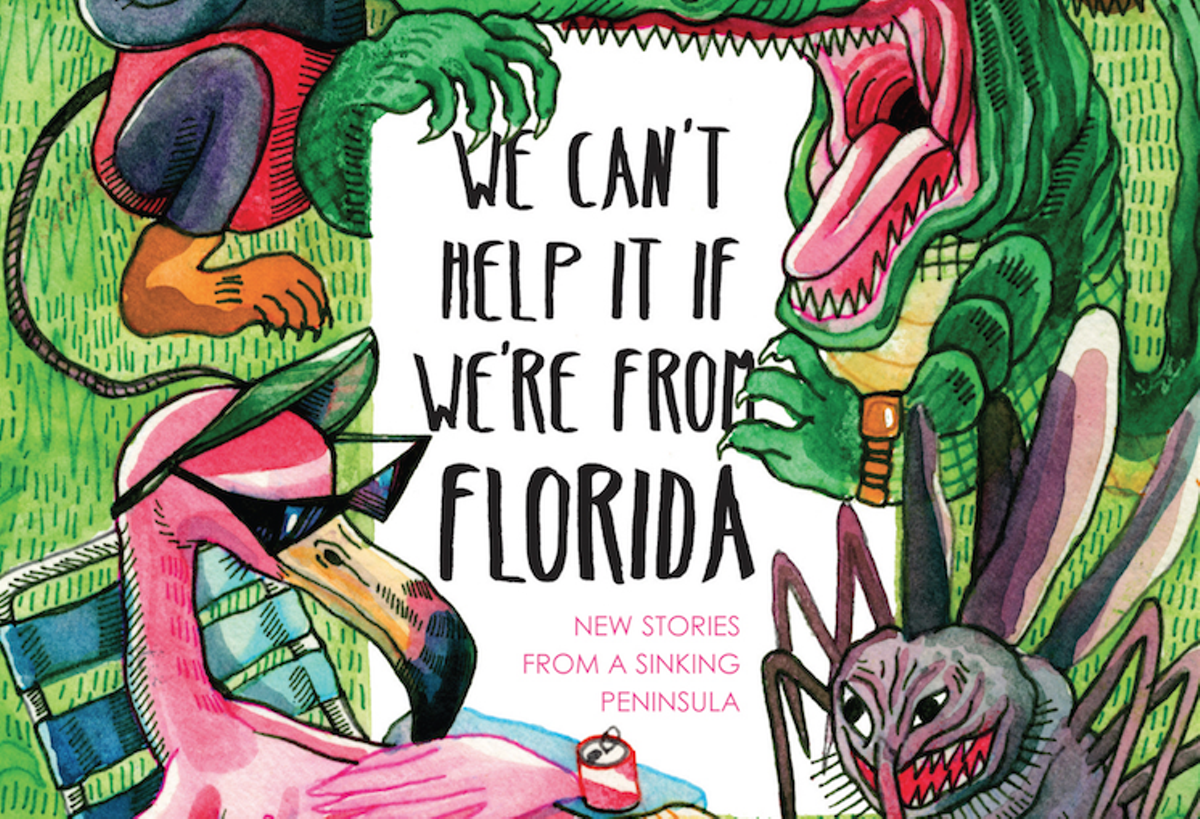

Burrow Press continues its hearty tradition of Floridian self-reflection with its latest anthology, We Can't Help It if We're From Florida: New Stories From a Sinking Peninsula. A variety pack of snack-sized tales, with a couple of poems sprinkled in for good measure, We Can't Help It nicely captures the prickly (heat) sensation of reserving the right to savage your own source, while defending it to others harder than a rabid possum. Below we've excerpted the foreword, written by anthology editor Shane Hinton; should you want to not only pick up a copy of the book but meet some of the writers (the readings commence at 8 p.m.), the release party on Wednesday promises to be the most Florida event you've been to, at least since the weather changed. Play shuffleboard, scarf Pub subs, suck down a brew or a boozy slurpee, scratch some Lotto tickets, even pet a baby gator (unless the animal rights folks nix his attendance). Flip-flops and shorts are suggested but not required. After all, it's only 70 degrees out there ... we wouldn't want anyone to catch pneumonia.

"What Is Florida Literature?"

By Shane Hinton

Somewhere in Florida there is a puddle of rainwater. It's out of the way – you wouldn't see it unless you went looking for it in drainage ditches and retention ponds, under oak trees and palmetto bushes. It is tepid and almost entirely undisturbed, refreshed every afternoon by summer thunderstorms so regular you can nearly tell the time of day by the cloud cover. The puddle is light green. In the still water, tadpoles swim in tight circles. Their tails flutter behind them. They collide with wiggling mosquito larvae. In just a few days one will eat the other, but for now they share the same space, birthed by the same water.

Down the street there is a young mother, pregnant with her second child, swatting at a mosquito on the back of her neck. Tomorrow the bite will be red and inflamed. She will wake up in the night to scratch it. A virus slips in her bloodstream between heartbeats. It spreads to her brain, to her unborn child. Her fever will be so low that she will not even go to the doctor. She will think herself cured before the week is out. A truck drives by trailing a chemical mist from sprayers installed in its bed, distributing poison that will kill the larval mosquitoes before they can break free of the water, but it is already too late.

A rattlesnake is coiled beneath the young mother's front porch, in the cold dirt, out of the sun. She steps over it on the way to pick up her daughter from daycare, a few weathered two-by-fours all that separates them. Later that afternoon, her daughter will walk up the same stairs. The snake will watch silently, knowing it can strike for more than half of its body length. The daughter has not yet learned this fact of Florida life. Her class is working on colors. Before he died, her grandfather taught her how to identify coral snakes. Red on yellow, kill a fellow, she remembers him saying, although the words have little meaning. She has never seen a coral snake.

The girl plays in the front room as the afternoon thunderstorm rolls in. Out the window she watches the branches of tall water oaks sway back and forth. They live more than an hour from the beach, but on hot days the air still smells like salt water. The windows fog over with condensation. The girl turns to the TV, where the news plays a slow crawl of events that feel distant. She can understand the people but they don't look like anyone she knows. Their skin and teeth are too light. Their hair is held perfectly in place. They speak in a measured non-regional dialect.

The rainwater runs off the roof of the small house and down through gutters clogged with dead leaves and acorns, into the ground. In the yard, in a small depression over the septic tank, another puddle starts to form. Fire ants, lifted from their hill, float on top of the water, scrambling over each other, using their drowned comrades as life rafts. The rain is so heavy it bounces off the ground like a solid thing. It filters through the sand and clay and limestone, leaving behind its impurities, ending up in a system of underground caves that stretches beneath the house and for miles north and south and east. Caves that kill curious divers by the dozens, the corpses of young men and women lost forever in the waters of the Florida aquifer, crystal clear and cold, bubbling up from the ground at natural springs, swimming holes in the middle of the woods, pumped out through giant pipes for drinking water, bottled, shipped away to the corners of the country on tractor-trailers.

And sometimes, without warning, the limestone crumbles in on itself, a sinkhole opens in the middle of a street, or a living room, or a pond. If you were standing near the edge of one of these, you would hear the clumps of dirt falling, falling, splashing into a reservoir deep below the surface of the earth, the sunlight suddenly illuminating fossils that haven't seen the sky in hundreds of thousands of years, the ground beneath your feet suddenly feeling less stable; that could be you down there, you think, with the fossils and the chunks of sidewalk and the living room furniture and the small, surprised fish, finding yourself relocated to an unrecognizable ecosystem, sinking deeper into that clear water as the sunlight gets farther and farther away, nothing to hold on to, soon to be fossilized yourself, preserved forever, in a place too easy to forget.