Employers looking for techies are offering attractive packages

Each day Julie LeBlanc, a product planner with Lucent Technologies in Orlando, dons a pair of sandals and walks from her bedroom to her office. As one of the new employees working in today's virtual office, she loves the freedom of working from home.

The computer industry is in the midst of a serious labor shortage which has triggered bidding wars, creating just the kind of of leverage that workers such as LeBlanc needed to turn the past decade of corporate downsizing into a profitable employee marketplace. Companies are actively seeking software engineers, Internet/Intranet programmers, web masters, java programmers, quality assurance testers and database administrators. Workers with these skills can find themselves enjoying the freedom of flex-time work hours, sabbaticals, stock options, fewer hours and casual dress codes.

In 1969, LeBlanc, of Maitland, graduated from Purdue University in Indiana with a degree in sociology and psychology. Instead of working in her field, she was hired and trained to work as a COBOL programmer. But shortly before the computer craze put industry in a frenzy, she left to care for her children: She never expected, 10 years and one divorce later, to be back in a job market that had changed so much.

"It was an extremely difficult period," she explained, "I had three kids, my youngest was two, my oldest only eight. I knew if I wanted to work I had to be competitive. That was the driving force for going back to school for my master's in computer engineering. I just told myself I had to get through it"

Although it took her four years to finish, twice as long other students, she now has a successful career as an analyst studying the Year 2000 (Y2K) problem.

The Y2K project redesigns older computer chips to recognize the new turn of the century digits 2000. Without this change, she predicts widespread hardware mayhem for the world's utilities, airlines, railroads, telecommunications and financial industries as computers systems read the "00" as if it were 1900.

LeBlanc knows her job is important and being able to work from home is a bonus. Flex time, the chance to set her own schedule, and taking time off without being questioned are the virtual office qualities she loves.

"I attend all my company meetings through conference calls," she says. When asked about what she'll do when videoconferencing replaces the traditional telephone? "Oh no," she sighs, "I guess I'll have to get dressed and start wearing makeup."

To capitalize on the market demand, novice programmers need to know their worth and be thorough in preparing for job interviews, LeBlanc says.

"Maybe Smart Money magazine said it best," she adds, "This is an employee market, people can ask for things they wouldn't have dreamed of years ago and they get it."

For some computer workers, the answer rests in the volatile world of contract employment. Contractors become hired guns, assisting overworked project teams in meeting deadlines they'd otherwise miss due to staff shortages.

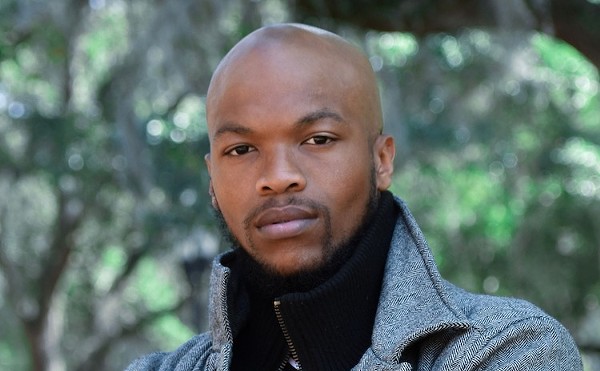

While specially trained as programmers, these workers may lack the guile to a suitable job in this volatile market. To fill this need, a number of job-placement firms in Orlando cater specifically to computer workers: identifying and studying local companies looking for help, working the phones, preparing applicants for interviews and negotiating terms with companies on the market for information technology experts. Maurice Dixon is a programmer on assignment with Fiserv, an Orlando company. Dixon says contract programmers in Central Florida average about $40 each hour, whereas full-time employees make $52,000-$53,000.

"In the private sector," he explains, "the money's not great for what I do. At my level - a programmer with 16 years' experience - I could easily ask for $105 or a $110 an hour."

According to Computerworld magazine's 1997 annual salary survey, Florida programmer analysts such as Dixon start at $41,000. Beginners can expect a salary of $36,000, data-processing managers about $51,000, information service directors $65,000 and top managers as much as $94,000.

To improve retention rates, computer firms moving to Orlando develop profiles of if profile certain candidates, striving to hire employees with a home or family or friends in the area.

Though Dixon admits he'd rather not move, he plans to stay a contractor. Not looking to one company for his income, Dixon says, gives him independence and confidence.

"When you're dependent on regular paycheck you're afraid to make a move, so people stay even though they don't like it. Now I have the flexibility I want."

While company employees typically are expected to work specified hours, contractors set their schedules. Of course, they must continue to get their work done. But they can attempt to wrap their personal lives around their work.

"I definitely have more freedom," he says. "If I don't feel like going to work until 10, nobody says anything as long as the work gets done. I still do my 40 hours but I decide what time I come in and when I leave. In the private sector you can't do that."

Dixon's advice to new programmers is to be patient and forget about being an overnight success. "Try to learn as much as you can and definitely focus in a certain area," he says. "The more you learn, the more choices you have."

The labor shortage in America's software market has schools like the University of Central Florida working overtime to keep up.

Dr. Chris Bauer, professor at the University of Central Florida's College of Engineering, has 600 undergraduates in his program and 100-150 grads each year, the bulk of which are nontraditional students in their late 20s and mid 30s. Bauer attributes this trend to the pressures of the marketplace.

"There's an incredible demand for software developers. I get 10 calls a week from industry looking for people," Bauer says.

The UCF program is filled with students switching jobs in mid-career and workers dissatisfied enough with their careers to return to schools to learn programming or other computer skills.

"This is a great career," Bauer says, "there's a computer in everything now, cars, stereos, kids' games. The modern cellular telephone has three and four chips, someone has to program these and we don't see any end to it."

Even though engineers are paid staggering salaries, Bauer warns not make a career choice based on money. "If you just get into it for the dollars, you won't be happy," he says.

The U.S. Commerce Department expects 95,000 new jobs to open in information technology departments each year. Companies with a desire to retain employees will be forced to get creative.

According to a recent article in Computerworld magazine, the hole in the marketplace will be better filled if companies learn to accept that today's workers have objectives vastly different from their parents. Columnist Jim Champy's article, "The Seven Ways to Court Today's Hottest Grads," gives some solid advice.

Champy urges companies to loosen their control over employee behavior, allowing them to come and go as they please. He suggests that employers learn to understand that this generation of computer workers often has a deep social sense and a love of education and environmental issues. Also, Champy observes, information technology workers truly believe technology can solve humanity's problems. He advocates company ownership, collaborative environments, internal entrepreneurships and fostering the sense that workers' jobs have a higher purpose.

Finally, Champy warns prospective employers how young grads feel about downsizing : "Like Milton's Lucifer," who said, ‘Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven' these talented Generation Xers want no part of companies that promised an exciting career but delivered conformity and a pink slip."

And with more job openings than there are workers qualified in the various information-technology fields, the applicants can afford to be selective -- even demanding -- in deciding who to work for and whether or not they will work from the home or office.