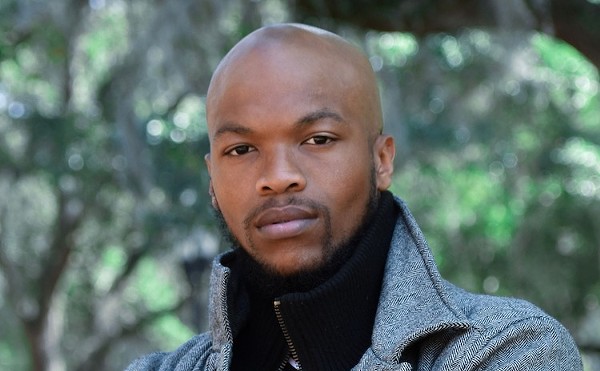

Isaac Lidsky has the sort of CV that gives new meaning to the term "renaissance man." Start with a stint as a child actor, playing the Screech-alike Weasel on the TV spinoff Saved by the Bell: The New Class. Then take a hard left into studies at Harvard Law. Pursue that thread into clerking duties for Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, followed by membership in a high-powered New York law firm. Finally, hang another tight left into his current gig as CEO of ODC Construction, an Orlando-based firm that performs construction-management services throughout Florida.

Still not impressed? Lidsky accomplished most of this while coping with retinitis pigmentosa, an incurable genetic disorder with which he was diagnosed in his early teens, and which left him completely blind by his 20s.

Yet far from considering blindness a curse from the gods, Lidsky has come to regard it a positive boon. In fact, he can't imagine where his life would be today had the loss of his vision not forced him to adopt a deeper way of seeing the world and his position within it. That epiphany and its fruits form the crux of his new book, Eyes Wide Open: Overcoming Obstacles and Recognizing Opportunities in a World That Can't See Clearly (TarcherPerigee). Part memoir and part motivational tome, the book urges all of us to re-examine our preconceptions of what our lives are and can be.

"At the end of the day, I think I was given this remarkable sort of peek behind the curtain of how the mind works," says Lidsky, reached via phone shortly before the book's March 14 release. "And I have set out to try to share that view with others. My passionate hope, my ambition here is that others will find it useful and valuable in their lives. In mine, it's brought me just immeasurable joy and fulfillment and success – success in the way I define success for myself."

At the heart of Lidsky's philosophy is the belief that the obstacles we perceive in our way are exaggerated in our minds, and sometimes wholly imaginary. It's hardly a revolutionary concept as inspirational literature goes, but in this case it's backed up by a strong scientific metaphor. The process of seeing, Lidsky writes, is centered not in the eyes but the visual cortex of the brain – which means that our perception of the world, usually construed as an automatic transmission of an immutable reality, is actually an active process that's both subjective and culturally determined.

As proof, he offers the example of Mbuti pygmies in the Democratic Republic of Congo, who have lived their entire lives in deeply wooded areas and never learned to manage concepts like foreshortening: Upon first exposure to distant herds of buffalo, they instead perceive tiny insects dancing directly before their eyes. Therefore, if we have to learn how to see literally, we can retrain ourselves to see emotionally and philosophically.

So if you're worried that blindness will leave you unable to work? There are screen readers and other assistive technologies for that. Convinced that your basic surroundings will be impossible to navigate without sight? You'd be surprised how your hearing alone can map a room. Petrified that disability will make you a perpetual charity case unable to start a family of your own? Well, that could just be what Stuart Smalley used to call stinkin' thinkin': Lidsky is a husband and father to – count 'em! – four kids.

To be fair, he also appears to have lived most of his life with somewhat greater monetary resources to draw upon than we typically associate with the differently abled. One example of "facing fear" he writes of was his decision to accept $350,000 in cash from his mother in order to save ODC, a company he had purchased without knowing the full extent of its financial precariousness. In the book, Lidsky puts such challenges into context by delineating just how comfortable the average American is when compared to the global standard. Within our relative luxury, he seems to argue, even blindness is a first-world problem. And in conversation, he explains that his "eyes wide open" ethos isn't about disability per se, but rather "a vision or philosophy that generalizes to anyone confronting any challenge. And frankly, independent of confronting challenges, just sort of living life."

So maybe it's up to the reader to decide how much of an answer Eyes Wide Open provides to one of the key conundrums of our time: Just what do we have a right to be dissatisfied with? How many of our troubles are actually self-created? Conversely, does our desire to believe that every aspect of our life is under our control mask an inability to face unavoidable concepts like failure and sadness?

"I think that we assume that we have less control over things than we do," Lidsky says. But he still distances himself a bit from the excesses of what he calls "positive psychology":

"There's this notion that happiness is the ultimate goal, the mean, the end, the everything ... I am agnostic when it comes to judgments of value. Whatever it is that you want out of life, you've got to figure it out for yourself."

No matter your own personal level of optimism, it's hard to not share his palpable enthusiasm when the discussion turns to the technological advances that are going to make basic, day-to-day living so much easier for most of us in the not-too-distant future – especially in an environment like Orlando, where even simple mobility can be such a challenge to the blind and the sighted alike.

"Look at things like Uber," he says. "Frankly, if I had perfect sight or whatever, would I want to buy a car and pay for insurance, or just use an Uber every time I'm going somewhere? And that's before we even get to, like, autonomous vehicles, which are coming soon. So I think it's a golden age for the disabled that we're living in."

Honestly, you can almost see it.

Orlando Weekly is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.