KISS alumnus Ace Frehley has taken a great many cues -- both musical and behavioral -- from Richards, so it’s no surprise that his No Regrets reads as a sort of Life lite. It’s likewise at its richest when depicting its protagonist’s formative years as a rebel without a press agent. And it becomes similarly nonlinear and free-associative as soon as the drugs really start to take hold. (The author’s, not the reader’s.)

Yet No Regrets clearly isn’t the book Life was, partially for reasons of simple geography. To a stateside readership, running with street gangs in the Bronx of the early 1960s isn’t quite as exotic or novel a concept as being a baby in London while Hitler’s bombs rain down around your head. But some of the difference is down to a gap in sophistication that exists between the two men to begin with. Frehley comes across here as generally amiable -- vindictive only when backed into a corner -- and more intelligent than the casual observer might immediately assume. But he can’t equal Richards’ vagabond soul or lacerating wit. (Frehley’s best bon mot: “I have a reputation for being one of the world’s worst drivers, but that’s not entirely well-deserved. I’m actually a pretty good driver; I’m just a really bad drunk driver.”)

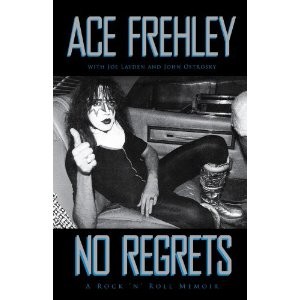

So Frehley isn’t Richards. Fortunately, neither is he his bandmate, Gene Simmons, whose 2001 harangue, KISS and Make-Up, regarded its reader as a slack-jawed naïf whose reactions could and needed to be controlled at every turn. Frehley and his cowriters, Joe Layden and John Ostrosky, are instead content to spin a few good yarns, then put them in the context of their central character’s mental state (both of the time and in retrospect).

Largely, this entails documenting the creative frustration Frehley felt as a member of KISS and the coke-snarfing, car-wrecking excess in which he sought to drown it. (That his bad habits only worsened after he left the band the first time is an irony Frehley chooses not to belabor.) The drug stories are the portion of the book with the most obvious appeal to nonfans, and they’re recounted with the familiar mixture of abject humiliation and vaudevillian zeal exhibited by many of those in recovery. (Frehley claims five years’ sobriety at this point.) The artistic lamentations are more hit-and-miss: At their best, Frehley convincingly argues that the regimented, almost Broadway-like nature of KISS shows became a yoke around his neck. By acknowledging up front how spoiled and petulant that sounds, he counts on us to realize that being dissatisfied with things we have no outward right to be dissatisfied with is practically the human condition.

He’s far less persuasive when he tries to overtly press the point that he was all about the music, whereas Simmons and Paul Stanley only cared about money. Yes, he puts it in those exact terms, but the idea is undercut less by inelegant language than by curious omission. For example, Frehley all but glosses over the KISS reunion era of 1996-2001 -- a topic to which Simmons devotes pages upon pages.

At this juncture, some judicious cross-referencing might be helpful:

“I thought it might be fun to throw on the Spaceman costume and makeup for old times’ sake

In retrospect, I realize I could have negotiated a better deal for myself, but I agreed to their terms for the benefit of all concerned, and especially for the sake of the fans.” -- Frehley, No Regrets

“Then came a series of conversations where Ace wanted a suite, and then a pair of roadies, and then five thousand dollars for guitar strings and popcorn and peanuts. Then he wanted another suite for his daughter.

‘I don’t care what you give Peter [Criss],’ he said. ‘I want more.’

He kept insisting, and still does, that he was much more important than Peter. This was all about his self-esteem.” -- Simmons, KISS and Make-Up

Oh, well. Recovery is an ongoing journey toward self-awareness. No Regrets finds Frehley at a very distinct point along that path. Or maybe he’s just saving some stories for the sequel, Okay, Maybe a Few.