It was Latin Night, just after 2 a.m. when the gunman opened fire. Most of the shooting victims were Latinos and people of color.

Plans to build a memorial in honor of the 49 lives lost have been years in the making, with little progress to show for it beyond an interim memorial, fundraising and design proposals for something more permanent.

The club's primary owner, Barbara Poma, founded the nonprofit OnePulse Foundation just over a month after the shooting, with the expressed intent of providing “immediate financial assistance” to affected victims and developing a permanent memorial to honor the lives lost, according to paperwork filed.

The organization has collected millions of dollars in donations over the years, and received a $10 million commitment in tourist tax development dollars from Orange County in 2018 to support the memorial’s development. So far, WFTV reported, over $6 million has been spent.

Seven years after the massacre, there’s still no permanent memorial. While some survivors and families of victims have publicly supported the OnePulse nonprofit’s work — including an annual scholarship program created in honor of victims — others have accused the organization of profiting off their pain.

“She doesn’t deserve any more money,” Gomez said of Barbara Poma, who isn't gay herself but opened Pulse in tribute to her brother, John, who died of AIDS in the early ’90s. “Poma has profit[ed] off this property since day one.”The memorial has been a source of controversy for years.

Family members of those killed recently urged elected city and Orange County leaders to intervene, according to the Orlando Sentinel.This week, Orlando City Council heeded the call. During a meeting Monday, they agreed to buy the Pulse property from its three owners — Barbara Poma, her husband Rosario Poma, and businessman Michael Panaggio — for $2 million, with a goal to build a permanent memorial at the site.

The unanimous vote of approval came after hours of testimony from survivors, community members and victims’ family members.Because the land purchase was on the council’s consent agenda (generally intended for non-controversial items) the testimony was not aired on the city’s usual live-streaming channels, and was not shared publicly.

But, by way of offering reassurance, Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer said on Monday that the city aims to ensure the process of the memorial’s development is “inclusive” of survivors and victims’ families.“I’m looking at this from an elevation of what is best for our community, what is best for the families of the victims or survivors in our community as a whole,” Dyer shared.

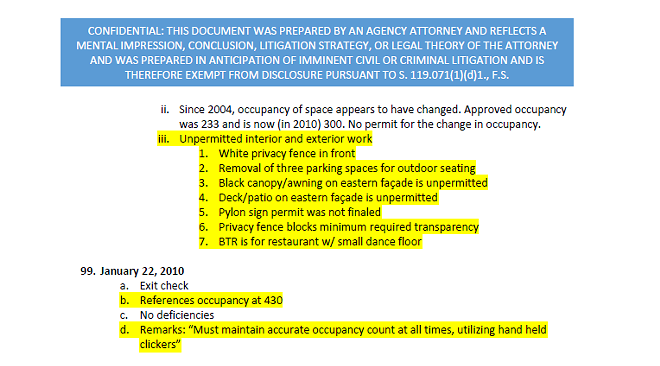

'I feel like they're not listening to us' For some survivors, including Gomez, there’s more to the story of the former nightclub — and two of its former owners — that must be addressed before they can find closure.A group of survivors and victims’ family members filed a complaint with Orlando police in July that describes code violations and unpermitted renovations at the nightclub on South Orange Avenue — some of which were known to city officials before the shooting occurred, public records show.

There was an unpermitted fence, eight feet tall, that a security officer had to punch a hole into in order to evacuate people trapped the night of the shooting, according to a police report.

City spokesperson Cassandra Bell told Orlando Weekly "we don’t have records that indicate whether a permit was received [for the fencing] or not."

Zachary Blair, a former patron of Pulse, has spent years collecting public records with the help of nonprofit Victims First in coalition with a group of Pulse survivors and victims’ families, the Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum.

Records obtained from the city highlight “capacity issues, unpermitted work, and other life safety violations that the city knew about,” Blair told city leaders Monday.

Documents reviewed by Orlando Weekly document multiple instances of the club exceeding capacity, as well as unpermitted interior and exterior work. There were also notes about the club’s exits.

In May 2016 — just one month before the shooting — fire safety noted “Exit Door or Hardware Inoperable” as part of their inspection of the property, without providing further explanation.

The club reportedly had six exits. But two of those exits led to a fenced-in patio that records indicate was initially added without a permit. One survivor told the Orlando Sentinel in 2019 that he used a couch on the patio as leverage to haul himself over the fencing to escape.

The city has said repeatedly told media that the club was in compliance with building code requirements. City spokesperson Bell told Orlando Weekly that records show “the Pulse facility was safe, that it met occupancy, fire and related requirements.”

“Pulse did not have a pattern of life safety issues, and in fact investigations did not show any meaningful violations,” Bell shared. Whenever the city identifies a life safety issue, she said the city will immediately work with a business to get it fixed. Work that's completed without a permit, she added, isn't necessarily done improperly nor does it indicate that it created a safety issue.

Bell confirmed that complaints filed by survivors earlier this year with the Orlando Police Department were under review, adding that the shooting had previously been "thoroughly investigated" by the FBI.

Support for a publicly owned memorial

Both Gomez and Hernández want a memorial that's free and open to the public, and believe it’s long overdue. But first, they want a third-party investigation into the Pomas and the property.

Mayor Dyer told the media last week that all or part of the nightclub will be demolished in order to build the memorial.

This raised a red flag for Gomez. “An investigation needs to come out before they do anything with Pulse,” she told Orlando Weekly, in an interview one day after the city council vote.“The truth needs to come out,” she continued. Although Gomez lives in Lake Mary, she drives through Orlando most days for work. It’s a constant reminder of the tragedy.

“I believe that if the truth comes out, I can actually put this behind me and actually live my life the way I’m supposed to,” Gomez said. “But the truth needs to come out.”

Hernández, who still receives medical care for his injuries, moved to Puerto Rico a year ago after calling Orlando home for 16 years. Like Gomez, he also reports trouble sleeping, and he seeks help for his mental health, even though he lacks health insurance.Both spoke to city leaders Monday during the public input portion of their meeting. Hernández called in, while Gomez joined other survivors, like Keinon Carter, who spoke to city leaders in-person.

Gomez called on the city to conduct a third-party investigation ahead of the club’s demolition, and called out the Pomas for “getting rich over us who really lived that night.”Barbara Poma, who ran the club, was on vacation in Cancun with her daughter the night of the shooting.

Several survivors voiced frustration over the idea of the city using $2 million in public funds to purchase the property from its owners.

City commissioners and mayor Dyer didn’t disagree.“I think this family shouldn’t get one more cent,” said commissioner Tony Ortiz, candidly. “The problem is, they own the property.”

Dyer, who holds an unpaid role on the Chairman’s Ambassador Council for OnePulse, admitted he disagrees “with a lot of the things that they [the foundation] did and how they went about doing it.”Speaking on the Pomas, he continued, “Do I want to pay them $2 million? No, I don't really want to pay $2 million. I would have rather seen the property donated either to us or to OnePulse.”

In May, the Pomas claimed they offered to donate their share of the property to onePulse earlier this year, but that Panaggio (the third owner of the property) wasn’t in agreement. Panaggio told the Orlando Sentinel that it was never his intention to donate the property.The city previously offered to pay $2.25 million for the property in 2016. Dyer admitted Monday that he was “a little bit relieved” that the deal eventually fell through.

Dyer, who's currently vying for his sixth term as mayor, has also faced heat from Zachary Blair and other survivors for what they view as a conflict of interest: Dyer's position on the Chairman’s Ambassador Council for OnePulse.

The chairman of the OnePulse foundation’s board of trustees is — or was — Earl Crittenden, an eminent domain attorney for GrayRobinson who was appointed by Dyer as the Office of the Mayor’s chief protocol officer for the city's international advisory board — a volunteer position.

Coincidentally, on Thursday — three days after Blair named Crittenden during public input on the Pulse purchase, and two hours after Orlando Weekly emailed both OnePulse and the city asking if Crittenden served in the Mayor's Office as well as the OnePulse board of trustees — Crittenden announced his resignation as chairman of OnePulse, effective Oct. 31.

“I wholeheartedly applaud and support the City in its effort to create a permanent memorial on the site for the families, survivors and the Pulse-affected community,” he continued. The nonprofit did not respond to Orlando Weekly's request for comment on issues raised by survivors ahead of publication.

Gray voted in favor of the sale anyway. But he suggested the city try to acquire the property through eminent domain, a legal process that allows the government to take private property if it’s for public use, after providing the owners with just compensation.

“We pay the fair price. We can control it. We can still do a memorial, but we don’t succumb to the owners who have done absolutely nothing that they promised they would do,” said Gray.What will it take to find peace?

Code violations at Pulse were a thornier subject. Blair said Monday that it was commissioner Patty Sheehan — the city’s first openly gay elected leader — who first told him and other survivors in 2019 to look into public records.

“You told multiple people that unpermitted renovations hindered rescue,” said Blair. “After four and a half years and thousands of dollars spent on records, we found this to be true.”

Sheehan addressed Blair’s comments after public input. “I was hurting,” she admitted, softly. “I was in a bad place. I was also very angry.”

But the responsibility for everything that happened at Pulse in 2016, she added, was on the gunman who entered the club and murdered 49 people.

“There is no cover-up here,” she stated. “If there are unpermitted renovations, the city didn't know about it.”

“I will never, ever be able to get out of my head the screams of those mothers as they found out their children died when I was on the street with them,” said Sheehan, her voice breaking. “So don’t tell me that I don’t care.”

Tiara Parker, who suffered multiple gunshot wounds the night of the massacre, said Monday that she felt like she’d been turned into a “cash grab” by the Pomas and the city.Although Parker herself survived, she lost her cousin, 18-year-old Akyra Monet Murray, at Pulse that night. Today, Parker is vice president of Victims First’s board of directors.

Hernández feels like the city has painted survivors like him and others who’ve spoken out about the Pomas and permitting issues as spreading falsehoods.

“We are not liars,” he told Orlando Weekly.

“We’re not a small group that is lying,” added Gomez.

The Pomas are defendants in an ongoing negligence lawsuit filed by 39 survivors and victims’ family members that accuses the couple of not maintaining sufficient security measures at Pulse.

Many of the plaintiffs have already reached settlements. A handful haven’t. Neither Gomez nor Hernández are named in the suit.

Gomez said she's prepared to continue her call for accountability "until the end of my days" if needed. "But I will have everyone that I know, know the truth," she said.

Subscribe to Orlando Weekly newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | or sign up for our RSS Feed