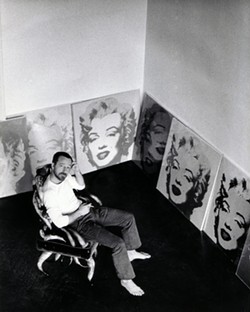

The first thing that you notice is the art. Wakefield Poole’s two-story Jacksonville townhouse is full of colorful paintings. Over the course of a half-century-plus of collecting, Poole has owned pieces by Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg and Jasper Johns; at one point, his collection included 24 Andy Warhol works, including the Marilyn and Electric Chair series in their entirety. “People asked me, ‘What are you doing buying art?’ And I explained to them that it’s my retirement. I didn’t have a pension,” says Poole. “When I needed money, I would sell a piece. And that’s what I’ve done. I sold my last Warhol three years ago.”

In addition to being an astute art collector, Poole has been a dancer, choreographer, theatrical director and chef (though none of these vocations offered a pension). But Poole is surely best known as a maverick and icon for his work in gay cinema, specifically pornography. Films like 1971’s Boys in the Sand and the following year’s Bijou are considered classic flicks that merged Poole’s sense of experimentalism with the X-rated.

“I hate the word ‘porno.’ It’s so downplaying. When someone says ‘porno,’ you know they have a problem with it,” he laughs. “It’s one thing if they say ‘X-rated’ films, or ‘experimental.’ I really thought that I was doing experimental films but I was doing it in a sexual medium. Why can’t someone make a pornography film that is beautiful to look at and not dirty and something you could be proud of?”

Orlando’s art-film fans will get an eyeful of what Poole’s talking about this Sunday, when the More Q Than A film series screens two of his films. And they’ll get an earful of stories in the post-film discussion.

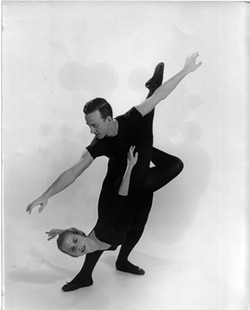

The elements of dance can involve action, space, time and energy, a deliberate fusion of movement and rhythm either subtle or extreme. When Poole arrived in New York in 1955, an accomplished 19-year-old dancer, he took those sensibilities and applied them to every facet of his creative life. After a stint with the acclaimed Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Poole accepted a series of notable Broadway dance roles, as well as regular work as a choreographer on The Ed Sullivan Show. But Poole was no wallflower to the radiating counterculture scene: He readily enjoyed psychedelics and soft drugs and even tripped out with the muddy, million-strong throng at Woodstock.

In his early 30s, Poole’s sex life was as actively charged as his career and newly psychedelicized sensibilities. During the late ’60s, Poole and his then-lover Peter Fisk began experimenting with colored lighting and film projectors, creating primordial multimedia presentations that bordered on avant-garde installations. Poole and Fisk had also made some playful experimental movies in their apartment, featuring the two of them cooking Julia Child recipes, filmed in stop-motion. These forays into left-of-field moviemaking soon caught the attention of the Manhattan visual arts scene.

Poole was commissioned to make a short film for an exhibit by the artist Vittorio. The acclaimed artist David Byrd, creator of now-classic posters for productions like On the Town, Follies and Godspell, along with Fillmore East rock posters, hired his friend Poole to create a kind of film-based installation at Triton Gallery. “I used 20 projectors and slide projectors to cast images on stretched fabric.”

After visiting the Warhol retrospective at the Whitney, Poole decided to make a movie document of the show. Shot in handheld color, the resulting 10-minute film, Andy, is an abstract tour of the exhibit. While attending the premiere of Warhol’s Heat, Poole hand-delivered a copy of the film to the silver-haired Pop Art icon. “I handed to him and I said, ‘Happy birthday.’ And he thanked me and laughed because he never really told his real birthday,” says Poole. “But he never really told me what he thought of the film. Of course, you could have hung out with him for hours and he’d never open his mouth. But it’s now in the Warhol Museum.”

One evening, Poole and Fisk went to see the gay porn film Highway Hustler. While hardly parochial in his views on sexuality, Poole found the film to be not only degrading, but quite evident of the soulless, bland and greasy elements that compromised then-porn.

“They called them ‘black socks movies,’” Poole laughs. “They were movies made with no story and it’s just people on a bed fucking and wearing black socks. Sure, I’d never made a movie. But I had ideas. And I knew that whatever I made would be better than that. And I already had a good life. But it totally changed when I made Boys in the Sand.”

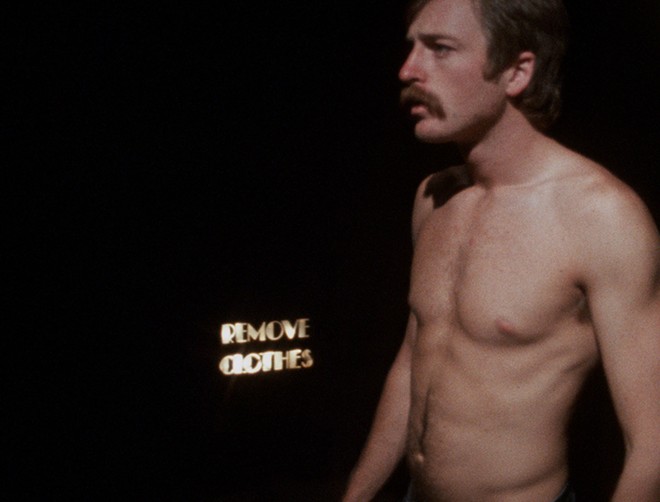

Boys in the Sand (1971) was an example of a DIY project-turned-overnight success. Made with a budget of $4,800 and shot over the course of three weekends on Fire Island, the film featured three segments of measured, languid sex scenes that were almost defiant of the blunt fucking of the 8mm sex loops of the day. Over the course of the film’s 90 minutes, leading man Casey Donovan interacts with men in scenarios that Poole based on the concepts of what he had described as innocence, hero worship, dreams, the attainment of love, and hedonism. In the case of attainment, in the film’s second act, Donovan tosses a mysterious tablet into a swimming pool. The water begins to bubble and churn and a nude man rises from the water, soon becoming the literal object of Donovan’s desires. While that device might seem trite by today’s standards, in the nascent world of gay pornography, it was downright revolutionary.

For the film’s premiere, Poole and co-producer Marvin Shulman rented the 55th Street Playhouse in Manhattan. Poole had chosen that theater since it was the same venue where were Warhol screened his films, like Kiss, Blow Job, and Couch.

“I didn’t do it to make a lot of money. I had no idea anyone would show up. I thought that I’d have 10 of my friends show up at the theater and that would be it.” Instead, on the opening weekend, Boys in the Sand raked in $28,000. The film received rave reviews in the New York Times and Variety, which featured a page-and-a-half article titled “Amateurs Bring in Bonanza.” The film is also acknowledged as the catalyst that helped make the following year’s Deep Throat such a blockbuster hit.

In the nascent adult cinema industry, there were no VHS tapes for commercial release. Poole and Shulman began selling 8mm versions of the film for $95 to satisfy the ongoing demand for the picture. “No one had ever sold full-length gay films before. I had John Gielgud come to the office in New York and buy a copy of Boys in the Sand to take back to London, since we couldn’t ship to Britain,” says Poole. “We finally started shipping everywhere in the world because we were getting so many requests.”

“Actually, I ‘came out’ publicly with that movie,” says Poole. “I mean, I’d never been ‘in’ but here I was professionally, coming out.”

After the immediate success of Boys in the Sand, the producer and filmmaker were suddenly flush with cash. Poole upgraded from his hand-cranked 16mm to a top-of-the-line Beaulieu 16mm camera. “You could play it backwards, you could play it forwards, slo-mo … you could do everything.” Now armed with state-of-the-art gear, Poole aimed his focus toward distilling his ideas of sex and surrealism into a cerebral 75-minute blend of both.