When he took on a simple writing and drawing assignment six and a half decades ago, Jerry Robinson had no idea he'd be carving a permanent, wicked grin on the face of popular fiction. He merely thought he'd earn a few extra dollars and some course credit.

Not yet out of his teens, Robinson had recently been hired as an assistant artist on Bob Kane's new Batman strip. The instant popularity of the character meant that their publisher was scrambling to fill pages with Bat-product. The opening was there for Robinson, who had been brought onboard to finish Kane's rough pencils, to generate a story entirely on his own.

"I decided that what Batman needed was some sort of an antagonist that was worthy of him," he says. "I loved writing short stories and humor pieces, so I decided that all good characters have some contradiction in terms. And I thought a villain with a sense of humor would be interesting."

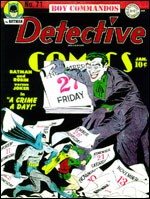

A white-faced clown on a playing card provided a visual impetus. The character that resulted – the Joker – is now often recognized as the most important villain to come out of America in the 20th century (Richard Nixon's best efforts notwithstanding). At the time, Robinson was happy to pick up the ancillary pay, and to have something to submit for a creative writing class he was taking at Columbia University in New York.

One wonders if Robinson's instructor felt adequately prepared to evaluate such pulpy pronouncements as, "Grotesque! The Joker brings death to his victims with a SMILE!" The kids of America, though, knew just what to think: that Bob Kane had done it again. As part of the latter's arrangement with his publisher, Kane enjoyed solo credit for all of the Dark Knight's printed exploits. Robinson's contributions remained in the realm of paid ghost work.

"It was known in the field, by professionals," Robinson says of his behind-the-scenes toil. And the publisher certainly seemed to appreciate it. As the 1940s commenced, this one-time kid assistant received greater responsibility for generating finished Batman art from scratch.

In hindsight, it's relatively easy to spot Robinson's hand at work. He was simply a better artist than Kane, with a superior sense of motion and perspective. His images struck a delightful balance between fisticuffs and moonlit mystery, one that's still a cherished nexus point for the character's myriad interpretations.

He wasn't the only one serving the Caped Crusader silently. According to Robinson, writer Bill Finger not only played a major role in the character's conception, but penned nearly all of the classic tales that bore Kane's byline.

"Bill, I think, should have been recognized as `Batman's` co-creator," Robinson says, "in the same sense that Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were co-creators of Superman."

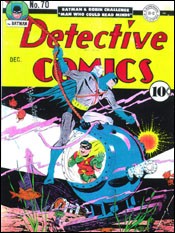

This hidden but fertile brain trust had produced another pivotal character in the Bat-saga. When Finger announced that he wanted to introduce a kid sidekick – comics' first – Robinson drew on his childhood reading to give him a look and a name.

"As a kid, I loved the Robin Hood stories, and was given as a gift a big volume of Robin Hood illustrated by N.C. Wyeth. I remembered his visualization of Robin, and so the first costume `was` derived from just my memory, because I had looked at those illustrations so often. So we named him Robin, and Bill added the slogan, 'The Boy Wonder.'"

• • •

One of the supposed cornerstones of American enterprise is the concept of intellectual property – the idea that a creator is entitled to all due recognition and reward that accrue from his creation. But it doesn't always work that way, and especially not in the comics business throughout most of the last century. The norm then was for writers and artists to sign away all legal rights to the characters they concocted – Siegel and Shuster surrendered ownership of their Man of Steel when they accepted their first $130 check. (Such undervalued imagineers sometimes then delegated responsibility for producing their actual stories to ghosts like Robinson, who had even less of a stake in the properties.)

"These were astute businessmen, and they knew what they were doing," Robinson says of the early comics publishers. "The artists, for the most part, did not. We knew nothing about copyright or legality, although there were exceptions to the rule."

According to the portrait painted in Gerard Jones' nonfiction book Men of Tomorrow (Basic Books) – which Robinson says is probably the best account of the early comics business – Kane was one such exception. Through a series of shrewd moves, he maintained a lucrative interest in Batman and kept his subordinates in the dark over how much he was paying their fellow ghosts (if he even let on they existed).

Robinson's pedigree within the field eventually led him to leave Batman and devote his energies to other strips – ones he could put his name on. His non-Gotham City work encompasses now-forgotten names like Atoman, Fighting Yank and Black Terror and more enduring personalities like The Green Hornet and even Lassie ("which I hated to do"). As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, however, Robinson found himself completing a gradual move out of the field.

"I could draw everything under the sun, `so I thought` it would be easy to get into book illustration," he remembers. "And when they asked to see my samples, I showed them the best of my comic-book work. And I couldn't get a job anywhere. They looked down on the comics. `So` I cut up panels from my comic-book work that looked like illustrations – didn't have `word` balloons, or if they did, I took them out. And I got work right away."

Pop historians love to point out that comics like the ones Robinson was slicing up would one day fetch princely sums on the collectors' market. More important, they would be recognized as having introduced an entire new generation of authors, artists and filmmakers to the transformative potential of wild adventures rooted in basic human decency.

• • •

Robinson made a successful transition into the arena of political cartooning, where his strips still life and Life With Robinson became newspaper staples for 32 years. But his CV hardly stops there. He has taught drawing classes. He has authored biographies and published acclaimed retrospectives of comic art. He has curated prestigious comics-themed exhibits in art galleries across the globe. And, spurred on by the success of a book he complied of the best political cartoons from around the world – a book, he says, that McGraw-Hill had considered of no interest to an American audience – he founded the Cartoonists & Writers Syndicate, which now disseminates the work of 350 cartoonists from 75 countries.

Some of his old cronies weren't so lucky. Siegel and Shuster were separated from their Superman assignment after years of legal wrangling, and their subsequent work didn't begin to approximate its popularity. Finger, despite finding jobs writing for TV, likewise failed to find the right outlet for his narrative abilities. He died broke at age 60 – whereupon the egocentric Kane finally began to give him some belated credit for "helping" shape Batman (nudged, perhaps, by a new generation of detail-crazed readers who had a way of digging up the truth). Kane was slightly more generous with Robinson, though he did insist that he himself had created the Joker, reducing Robinson's influence to having sketched that infamous playing card.

"If I had remained in the field, I might have had the same trouble," Robinson says of the struggles of Siegel, Shuster and Finger. "But I was always challenged by something I hadn't done before."

Some of the challenges he's met and mastered appear to define heroism of a distinctly grown-up kind. How he helped free an artist who had been jailed and tortured in Uruguay. How he got a Russian artist out of a gulag and smuggled his first royalties into Moscow. To each of these remembrances, Robinson appends a casual "but that's a long story" – as if we all have such tales under our utility belts.

One of his proudest accomplishments, though, was his central role in the legal negotiations that finally gave Siegel and Shuster their due. In the late 1970s, when Siegel was clerking for the California Public Utilities Commission and Shuster had gone certifiably blind, Robinson learned that they were still fighting DC Comics for their fair share of the Super-pie. Using his position as a past president of the National Cartoonists Society as a springboard, Robinson conscripted some major personalities into Siegel and Shuster's PR cause – men like cartoonist/historian Jules Feiffer and author Kurt Vonnegut ("who I met at Cape Cod").

With the high-profile heat on and lawyers working pro bono, Robinson was able to convince DC to pay Siegel and Shuster a lifetime annual salary and provide them with health insurance. And he got them a bonus that resonated on a more personal level. From that day forth, all of Superman's adventures would bear the legend "created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster."

Robinson says he was doing a favor for some friends: "I used to double date with Joe before I was married." But he was also fighting for a larger principle. He knew all too well that it's in everyone's best interest when the world knows exactly who did what.

• • •

At the age of 83, Robinson says, he's almost busier than ever. Though his son now runs the syndicate he started, he still plays an active role in it. He curated a 2004 exhibit about superheroes at the Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta. He's doing a lot of writing. His landmark volume, The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art, is about to be republished in an updated edition by Dark Horse Press.

And through it all, he's finally come to accept a nickname that used to make him cringe when he was a 17-year-old cartoonist working alongside partners a few years his senior.

"Being the youngest, I wanted to be seen as older," he says. "So they started kidding me, calling me 'The Boy Wonder,' which I really hated.

"Now, if you want to refer to me as the Boy Wonder, it's OK."

Jerry Robinson

Appearing at Florida eXtravaganza

Friday-Sunday Jan. 27-29

Central Florida Fairgrounds