Plastic ice chests under a canopy in the parking lot of Stardust Video & Coffee are not where you'd expect to find some of the best shrimp in Orlando. Then you learn that they came from the Atlantic Ocean, unloaded from boats on a dock at Port Canaveral, just about 60 miles due east from this point of purchase, and it starts to make sense.

Cinthia Sandoval, 26, patiently explains this to customers, most of whom are new to the Wild Ocean Seafood booth, itself a recent addition to the weekly Audubon Park Community Market. As the outreach organizer for Wild Ocean, she lays out the sweet pinks alongside the prized browns, all indigenous to the Atlantic. Both look plump, and a whiff brings only clean ocean essence. The price, which changes from week to week, is competitive with what Publix and Whole Foods charge for imported shrimp. The quality, however, ranks higher. This Atlantic-caught seafood is said to come from some of the cleanest water and holds a premium, typically costing about a dollar more per pound than shrimp from the Gulf.

Consider that 90 percent of shrimp eaten in the United States is imported, and you'll understand how rare the domestic variety is. Then comes the clincher: This is the same supplier used by the World Famous Dixie Crossroads Restaurant in Titusville, famous for its fresh-caught, fried-crisp Atlantic shrimp and fish.

In fact, it's all in the family. Dixie Crossroads and Wild Ocean Seafood (formerly Cape Canaveral Shrimp Co.) founder Rodney Thompson, 79, built both businesses on his belief in the inherent value of the premium "fresh-caught" local product. He eventually divvied up the operations between his two daughters, Laurilee Thompson, 57, and Sherri McCoy, 55, when he retired in 2005.

Today there are multiple generations of family and friends invested in Wild Ocean Seafood; their roots, fishing industry activism and hard work keep them alive in an industry threatened by global competition, rising fuel costs and impending legislation that could potentially ban the catching of designated "overfished" species.

The legislation is called the Magnuson-Stevens Reauthorization Act, and it was passed in 1976 and revised in 2007 in the last days of the Bush administration. It came with a timeline, which meant that if overfishing had not been addressed by 2010, dwindling species were off-limits through any and all actions, even a permanent ban on bottom-fishing – including snapper and grouper – over a 10,000-square-mile area of the Atlantic, from Virginia down to Key West. But enforcement of the act has been put off repeatedly, so much so that people stopped paying attention. The most recent postponement expires in June, meaning that a ban covering much of the Atlantic seaboard could start then, unless Congress acts quickly.

The ban is supported by a handful of large environmental groups, the largest being the U.S.-based Pew Environment Group. The self-described "major force in educating the public and policy makers" is involved in showdowns with fishing industries in New England, Hawaii and Australia.

"The Magnuson-Stevens Act requires that depleted fish populations be rebuilt as quickly as possible," Pew spokesman Lee Crockett said in a 2007 press release. "But shortsightedness and political pressure has kept too many fish populations from reaching healthy, sustainable levels."

McCoy says it's been difficult to grasp the implications of the Magnuson-Stevens act. "One of the last things that Bush did was went back in [to the MSRA] and put some reauthorizations in it, which say if the stock is declared overfished, they only have a matter of a year or two before they had to do something about it."

In Wild Ocean's waters, it's bottom-fishing that could be banned by summer; down deep near the ocean floor is where approximately 90 different types of fish live, including good-eating types like snapper and grouper. Obviously, that would put Wild Ocean, and other local fishing businesses, in jeopardy.

Over at Wild Ocean Seafood headquarters in downtown Titusville, co-owner Jeanna Merrifield, 53, is making plans to attend the Feb. 24 "United We Fish" rally in Washington, D.C. Protesters from around the country are set to gather on the steps of the U.S. Capitol to send the message to Congress to extend postponement of the ban until there's better science to indicate that such a draconian measure is necessary to remedy what they feel is a ridiculously exaggerated fear of overfishing.

Merrifield owns Wild Ocean with her husband, Mike Merrifield, 55, and her lifelong friend (and Thompson's daughter) McCoy. McCoy is on the list to speak at the D.C. rally, as she was just voted incoming president of the Southeastern Fisheries Association.

Mike Merrifield notes that within a month it'll be the season for snapper. He is eager for intermediate measures to be enacted before economically crushing measures are enforced. "I have had fisherman actually leaving the country to go fish other places," he says, "in Mexico and Central America, because they might just shut down snapper and they are getting ready to shut down the whole snapper-grouper complex. There are over 80 or 90 different species of fish that can no longer be caught out there."

It comes down to two schools of thought, he says. "On one side, there are fishermen saying that since the dawn of time the way we fish is to fish until it is no longer economical to catch that fish anymore, and then you leave it alone and go to something else and it replenishes. And we go from there to something else, and then we may eventually come back to that fish, but in a time frame that allows it to come back."

His color starts to rise as he continues. "Then on the other hand you've got conservationists with a lot of money, a lot of money – big trusts are involved in conservationism – that are saying ‘Oh, we are killing all the fish in the sea and there is going to be no fish in the sea …' and that is a lot of bunk."

Jeanna Merrifield questions the motives of conservationists like Pew. "The only thing that I can look at, with my experience, is [Pew's] federal income return from 2007 … and this trust has billions of dollars. It is so easy for them to push their agenda," she says.

Congressman Bill Posey, of Florida's 15th District, says he doubts the government even has the authority to declare a total ban on bottom-fishing.

"NOAA and the National Marine Fisheries Service are overreaching in believing that they have the authority to terminate all bottom-;fishing," says Posey. "I don't even believe that they have the authority to do that."

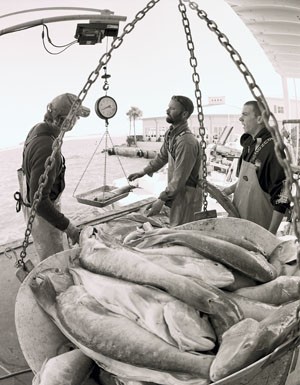

The trio of owners who now run Wild Ocean oversee two points of operation: There's the processing plant and market in Titusville and a more scenic dockside locale in Port Canaveral. The latter is where the rusty trawlers come to unload catches of shrimp and fish, which are then trucked over to Titusville for cleaning ;and staging.

Mike Merrifield, whose education and background are in computer science, spends most of his time at the Titusville plant, located in a big-box-size storefront in a drab downtown strip mall on South Park Avenue. The bright blue-and-yellow "Wild Ocean" signage is what catches your attention. Inside, there is product and activity everywhere. Long display cases filled with crushed ice hold whole flounder, tuna, snapper, stone crabs and scores of other species – some imported, but most local. And there's an interesting assortment of prepared foods.

"For all the locals over here, mullet is a big, big fish. We smoke mullet and we make a smoked mullet dip," says Merrifield, who is so fussy about seafood that he rarely eats anything he hasn't selected and cooked himself.

On a recent weekday, the concrete floors are still wet in the adjacent processing room, where the action takes places Monday through Thursday, when loads of whatever's fresh off the boats are delivered. About 25 people wearing rubber boots, aprons and gloves surround the stainless-steel tables in the center of the room to scale, prep and stage the catch. Then the room gets a thorough hose-down and tools and equipment are hung up to dry.

Mike recommends the golden tilefish on this day, reaching into tubs of 3-foot-long iced specimens back in the cooler. "This is a pretty fish," he says, pointing out the telling gold spots dotting it. His other prize on this day is coveted royal red shrimp, an oversized variety bigger than crawfish. He tears into a purple net bag sitting on a forklift to show how they are frozen solid but not stuck together. That's because "freezer boats" are equipped with a tank of icy, briny water – so cold and salty that when the shrimp are tossed in, they immediately freeze solid.

Over at the other part of the operation, Sherri McCoy has a rare view from her second-floor office at the Port Canaveral location. She sits, mostly phone in hand, with windows that open onto the water. The sheer size of the cruise ship in the background makes it look as if it's been collaged just over her head. At night, the departing cruise ships travel like a lighted parade before their dock.

McCoy points to the photographs of boats that line her walls. "These are the heart of our business," she says. "The relationships we've built with our boats are what keeps us going."

Boat captains are independent contractors, though some tend to fish for just one company. Wild Ocean works with about 130 fishermen and boats. In recent years, the company has worked with more independent fisherman, but at the same time it has lost bigger commercial shrimp boats that have gotten out of the business.

McCoy's family history goes back to early homesteaders of Blue Springs in the 1800s. The fishing connections go back to her entrepreneurial dad, Rodney Thompson, who invented the industrial rock-shrimp splitter, a device that made it cost-effective to harvest the tiny piece of mild meat in each rock shrimp, making it a cheap cousin to lobster. That kicked up an overfishing controversy in the 1980s, when rock shrimp in the Gulf and Atlantic waters were depleted.

Thompson and his wife, Mary Jean, were not popular for their support of conserving waters for sustainability. An article from the September 2007 issue of National Fisherman magazine recounts how local fisherman opposed Thompson's cautionary approach, only to come around eventually.

These days, McCoy says, it's not unusual to see her dad in his wheelchair watching the boats be unloaded, including his own personal boat, his mind still full of ideas and his body aching to get back to work.

"All of us worked for him as kids," says McCoy. "We started out counting screws, and then when we were building boats … our job was to wax the molds and take the wax off," she says, laughing. "I always loved dealing with the fisherman when we started building the commercial fishing boats."

McCoy's sister, Laurilee Thompson, was one of the few female boat captains, and she was very successful before settling in to her tenure at Dixie Crossroads. McCoy's son, Josh, 25, is shaping up to be her right-hand man for dealing with the captains on ;the docks.

There's a lot of family interaction at Wild Ocean Seafood. The Merrifields' sons – Michael, 25, and Christopher, 28 – are active in the day-to-day business. Another son, 29, lives in New York, explains Jeanna: "He actually does our ads and advertising." There are few titles at the family company; they each do whatever it takes, hopping from one facility to the other.

The goal is to engage customers, especially those searching for shrimp and fish fresh out of local waters. That's the reason Mike Merrifield says he's happy that Cinthia Sandoval brings shrimp to the Audubon Park Community Park in Orlando. "Because we've always been about trying to educate people about the seafood that they are buying and putting into their mouth."

The important thing is to ask, he adds, "Where does that shrimp come from? There is imported and farmed and wild-caught – there is a lot of different things that you can buy. You just need to know what you are buying. And then you can associate a taste profile with that product, and say, ‘OK, I like this one better. This one suits my needs better.' Because I think that you find when you get a local wild-caught product, you're going to like it so much more."

[email protected]