Gray trees, bearded in Spanish moss, stand at attention before soft, glowing sunsets. Birds fly overhead, their reflections mirrored in the water below. This is the iconic imagery associated with the old Florida landscape.

There’s nothing quite so scenic that can be seen from behind the bars of the Central Florida Reception Center, a prison located on the east side of Orlando. The best view available around the jail is that of the cow pastures that spread out beneath the power-plant silos towering over the 528 Beachline Expressway to the beach. For most of the inmates, the natural environment exists only in memory.

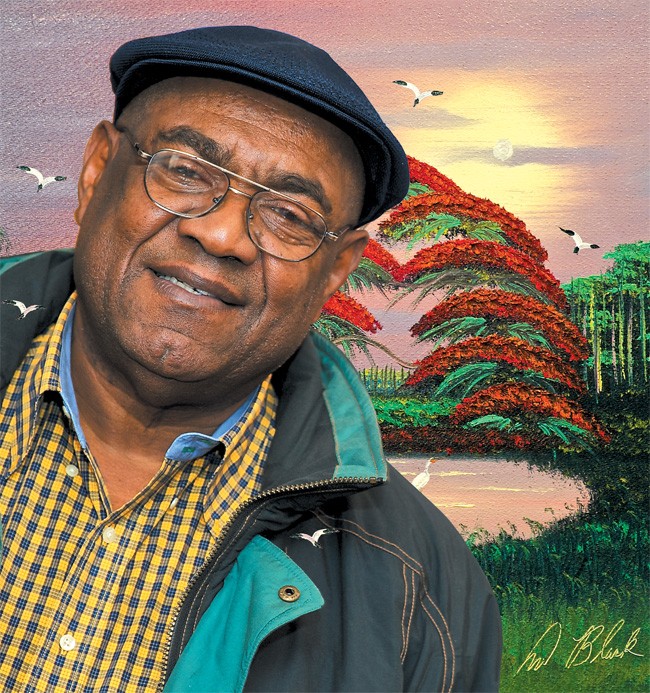

And it was from memory that artist Al “Blood” Black painted the pastoral, Florida landscapes that adorn the walls of the laundry room, cafeteria and hallways of the jail, where he served 12 years for fraud.

Black was one of the legendary Florida Highwaymen, a group of African-American traveling artists who peddled their idyllic, stylized Florida landscape paintings door-to-door and from the trunks of their cars, beginning in the late 1950s.

The works of the Highwaymen were once written off as kitsch – the kind of art your grandma living in Boca might hang over the sofa, or the stuff you’d see on the wall of a crusty, beachfront motel room – but since the mid-1990s, when the work of the Highwaymen was rediscovered by arts enthusiasts, the value of the paintings has soared. What once were cheap souvenirs became coveted art objects, and today paintings by one of the 25 men and one woman who are part of the Highwaymen movement can easily fetch upwards of $1,500 apiece.

Black, now 65, isn’t the kind of artist who was born with a palette in his hand; the tools of his original trade were a steering wheel and a smile that stretches across his broad face. He was a traveling salesman who started with the Highwaymen by selling their work, but he eventually started painting, too. His biggest body of work can’t be viewed at a gallery, though, and the only ticket that can get you in to see it requires a mug shot and a jailhouse jumpsuit. It’s all housed here in the Central Florida Reception Center.

When inmates are booked into to the jail, they’re assigned jobs to do. Some work in the cafeteria, others in the laundry room. Black was asked to do what he liked best.

“The warden asked me if I could paint some murals of my landscapes,” Black says. “They heard of me in the news, that I was a painter, so they asked me to paint.”

In the years he spent locked up, Black painted more than 80 murals on the jail’s walls. They’re in halls, offices, storage rooms, the outside gymnasium, waiting areas, the chapel and dining hall.

Black was born in 1946 in Barlow, Miss.,and he grew up picking cotton and doing odd jobs. He quickly developed an urge to travel, so when a farm contractor offered him a job recruiting workers, he took it. He often found himself in Florida, and in the 1960s, he took a job selling typewriters for the Fort Pierce Typewriter Co. During his sales travels, he often encountered a group of African-American artists, dubbed the Highwaymen, who painted Florida landscapes and sold them door-to-door or right out of the beds of pickup trucks.

Black was born in 1946 in Barlow, Miss.,and he grew up picking cotton and doing odd jobs. He quickly developed an urge to travel, so when a farm contractor offered him a job recruiting workers, he took it. He often found himself in Florida, and in the 1960s, he took a job selling typewriters for the Fort Pierce Typewriter Co. During his sales travels, he often encountered a group of African-American artists, dubbed the Highwaymen, who painted Florida landscapes and sold them door-to-door or right out of the beds of pickup trucks.

Black befriended Alfred Hair, one of the first Highwaymen and the leader of the group, who recognized Black’s potential as a salesman for the group. Hair drew Black into the business, and he quickly became a prolific salesman.

“I would sell to anybody, from motels to doctors and lawyers,” Black says. “Whoever I came across, I would try to get them to buy. Nobody was as good as me at selling. I could sell ice in Alaska.”

Black took the Highwaymen’s business to new heights. He expanded their market, selling paintings throughout Florida and beyond, though the law would sometimes get in the way of business.

“I traveled up the Atlantic seaboard, from Key West and all the way up to Portland, Maine,” he recalls. “Sometimes I would get thrown in jail for a few days, since a license is required in each state to sell. It was hard times.”

Black’s painting career got started more as a necessity than an artistic urge. As he traveled, the paintings got bumped around and sometimes they needed a bit of touch-up.

“When I would be traveling with all the paintings in the back of my Cadillac, they would get smudged,” he says. “So, I would have to fill it in – a little of the sky, a little of the tree.”

When he would return to the Highwaymen’s home base in Fort Pierce, Black learned techniques from the other artists, too. The group, known for mass-producing many of its paintings, would often have backyard barbecues where the artists would work on the next batch of landscapes together. Sometimes they even painted in assembly-line order: painters would specialize in creating parts of a painting – one might paint water, another would do clouds, yet another would do trees. At times, the group could complete 35 to 40 paintings in one evening.

Black and the Highwaymen were economic in their artistic approach, carefully minimizing the number of brush strokes and amount of paint needed to create a piece. To keep expenses in check, they would use cheap materials, like house paint and Upson boards used by roofers, whenever they could. They would build frames out of door trim.

The paintings didn’t sell for much – the prices ranged from $15 to $25 per piece – but with Black’s help, the artists could sometimes bring in as much as $5,000 a week in sales.

By 1970, Black and the Highwaymen had earned a pretty good living selling paintings. Black says he was driving a nice car (at one point, he says, he owned three Cadillacs) and in the spring of that year he married and started a family.

By 1970, Black and the Highwaymen had earned a pretty good living selling paintings. Black says he was driving a nice car (at one point, he says, he owned three Cadillacs) and in the spring of that year he married and started a family.

In the summer of 1970, he and Alfred Hair had planned a meeting to discuss a trip to sell some new paintings. The night they were supposed to meet, though, Hair was shot and killed in a brawl at a Fort Pierce bar called Eddie’s Drive-In.

Without their leader and visionary, the Highwaymen lost focus. According to The Highwaymen: Florida’s African-American Landscape Painters, written by Gary Monroe, the painters continued to work through the 1970s and ’80s, but the organization disintegrated. “There was nothing to shoot for after Alfred died,” Monroe quotes one of the Highwaymen, Hezekiah Baker, as saying.

Demand for the paintings dropped as well. Fewer people were traveling Florida’s meandering state roads, where the Highwaymen often hawked their wares, opting instead to take newer highways to their vacation destinations. Laws forbidding solicitation in public places made it harder to find places to peddle. By the 1980s, the highly stylized paintings were beginning to look dated and generic to people.

As the Highwaymen’s tight-knit group was falling apart, so was Black’s life. He got involved in drugs, and by the mid-1990s, he wound up in jail on a string of drug charges. In 1995, the St. Petersburg Times (now called the Tampa Bay Times) profiled a Kissimmee art collector who had rediscovered the Highwaymen and was trying to reach out to Black, who had been in and out of jail and was living in a dilapidated boarding house in Fort Pierce. He had stopped painting, according to the story, because he had no money for paint or supplies. Two years after that story was published, he landed in jail again, this time for allegedly conning money of an elderly widow who had tried to help the struggling artist. Prosecutors said Black used the money he got from the old lady to buy cocaine, and he was sentenced to 12 years, which he served at the Central Florida Reception Center.

Part of the jail specializes in housing inmates with special medical needs. Black was HIV positive. One of the guards at the jail (who is unnamed in this story, for his security) often allowed Black to paint in his office near the jail’s laundry room. During a recent tour of the facility, the guard’s face lit up as he showed off the work Black did during his imprisonment. Most of the landscapes were painted right on the cold, concrete walls of the jail, with permission from the warden.

During his time at Reception Center, Black developed a new trademark for his paintings. He had always liked to include a trio of birds, flying in formation, in his works. He said they represented the Holy Trinity. In jail, he decided to add a fourth bird.

“The fourth was out of formation,” Black says, “symbolizing my fall from grace.”

The prison murals create an ambivalent scene in the halls of the Reception Center. Everglades grasses and flowering royal poincianas are juxtaposed with fire extinguishers and “no smoking” signs. According to Monroe, who also authored a book about Black’s prison works called The Highwaymen Murals: Al Black’s Concrete Dreams, the population at the jail knows that some of the artist’s best works are embedded in that place.

“Both prisoners and staff, by and large, realize the worth of the murals,” Monroe says. “Images of idyllic Florida transform the institution, and prisoners speak reverentially under their influence.”

When asked whether he thinks the current administration at the jail or at the Department of Corrections in Tallahassee realizes the historic and cultural significance of the paintings on the jailhouse walls, Monroe is philosophical.

“Nothing with form is permanent, and the murals are where they belong,” he says. “They’ll age, though vandalism hasn’t been a problem. Maybe they will be whitewashed over at the call of a warden, or maybe Tallahassee will have the buildings razed and replaced with new buildings. The paintings will have served their purpose.”

While Black was doing his time, the paintings of the Highwaymen boomed in popularity. Paintings that had been selling for just a few bucks at a thrift shop in the late 1980s and early 1990s were rediscovered by collectors and were suddenly fetching hundreds and even thousands of dollars. In 2004, all 26 of the Highwaymen were inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.

Black was released from the Central Florida Reception Center in 2006, in time to cash in on the renewed popularity of the long-forgotten artistic movement. By spring of 2007, he was back at it: painting and selling, wheeling and dealing in art.

“As soon as I got out, I moved back to Fort Pierce,” he says. “I contacted all the Highwaymen and started doing business again.”

These days, he’s making a living as an artist, and he can often be found traveling the coast again, from Cocoa to Orlando to Fort Pierce to Winter Park. He’s a regular at art festivals and fairs, selling his landscapes for prices ranging from $350 to $1,500, and for those who can’t afford those prices, he also sells T-shirts, buttons and postcards adorned with his works on his website.

He’s a giant of a man who has to duck his head as he enters his vendor tent at a festival in Hannibal Square in Winter Park. His Southern drawl, booming voice and charming demeanor always get the attention of passersby. When they stop to admire his work, he smiles widely and hands them his card – just like he used to do back in the day when he was driving his big old Cadillac with a trunk full of paintings up and down the eastern seaboard.