The first time I saw one of Grady Kimsey's primitive tribal sculptures was approximately 20 years ago at the Maitland Art Center. Among all the pretty paintings and lovely vases, here was this figure formed from dark clay, looking not of this earth yet clearly composed of its substance. A wise mentor of mine at the time steered my disturbed reaction so that I opened myself to the artistic alchemy and felt unsettled from deep within. I never forgot the sculpture or Kimsey, though his name has been quiet on the Orlando front for many years, mostly because his sculpture was exclusively represented by the Connell Gallery in Atlanta.

Now approaching 79, Kimsey resides in both Winter Park and New Smyrna Beach with his wife, and he is still creating art that's as lively as his blue eyes and as engaging as his gentle Eastern Tennessee accent. His history is full and fascinating — born in Tennessee in 1928; the first student to receive a B.A. in fine arts from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville; later awarded a master's in education from Rollins College; a faculty member at Seminole Community College where he served as the gallery's director until he retired; and a full-time artist for the last 18 years.

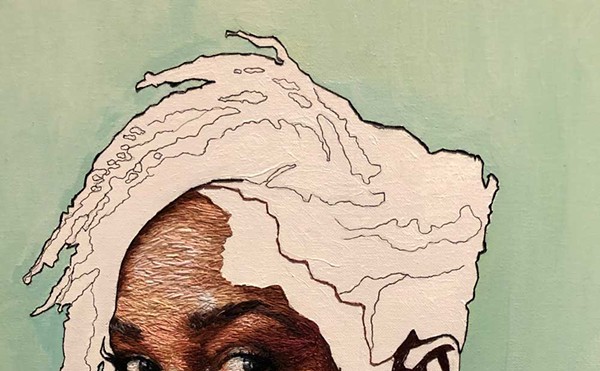

Earlier this year, Kim Sumner and Karen Carasik talked the reticent artist into sharing some of his new paintings at COMMA Gallery, and the show was a wild success; artists and the general public turned out in unanticipated numbers to purchase the luminary's work. But the limited display merely whetted appetites, and so opening this week at COMMA is a thunderous collection of what the prolific artist has been up to for the last two years: paintings, sculptures (no longer exclusive to any gallery) and collages, as well as his latest innovation — painted sculptures and collages with painting. One sweeping look around the airy gallery feeds the eye with brilliant color not typically associated with Kimsey's primitive palette, though his traditional sculptures are well-represented, frequently adorned with his recurring talismans, most notably birds and fish. Intensive inspection yields details within details that offer no answers to his mysterious presentments, all of which make you feel you're being delivered messages from another dimension.

In person, Kimsey is tall and outdoorsy, with a distinguished gray beard. He claims he's a man of a few words, but he's easy to engage in conversation. His only concern when we talked was that he make it home in time to watch the UT Volunteers take on California.

Orlando Weekly: You're better known for your sculpture, but it's painting that is the focus of this new show.

Grady Kimsey: I was trained as a painter, and came to Florida and painted for a few years and exhibited at the Center Street Gallery. Then picked up a piece of clay and that took over for a while, for several years, and I started doing pretty big pots with weavings in the top of them — Maitland Art Center has one in their permanent collection; if you're ever down there take a look. And then that evolved some way into sculpture, which I've done for several years and now I'm moving back into painting and sculpture — working together, I hope.

There was a multicultural aspect to your tribal sculptures way back when "multicultural" wasn't a word being thrown around? And the new paintings that I've seen follow that same expression. So you were obviously interpreting aspects of multiculturalism in your work then and now, even though you're using a new medium.

People tell me that they that they can tell it's my work — whether it's a painting or a piece of sculpture — and I hope that's true, because I want it to come from the heart. And I try to influence people. And I hope it isn't derivative of any sort other than I do have an affinity for pre-Colombian work, for primitive work because it's honest — for either religious or utilitarian reasons — and not just to sell. I hope that's where it comes from.

When you say it comes from the heart, what are you pulling out of yourself?

This may come as rather a surprise, but this is true. When I work, I work on maybe 25 or 30 pieces simultaneously, because if I start things and finish things in a sitting, it becomes, well, I work on it so much that I'm too concerned about what people are going to think of it. So I've learned to put myself pretty much in an alpha state where I can work on all these pieces and not be too concerned with the finished product. And when I'm finished with a piece, it always surprises me that I have worked on it and finished it. It's just fresher to me that way. And I try not to be influenced by other artists.

Did you teach that methodology to your students?

I think I did it more than maybe — I really tried to. I want a student to find his own voice, not mine, because we're not the same people; we haven't had the same background — all those things. So I tried very hard, and I look at my students' things once they are out practicing art and I don't think you can tell they had the same teacher, which is good, as far as I'm concerned.

How did you empower your students to find their own voices?

I just encouraged them to be honest with their work, to work because of who they are and not be too concerned with what other people thought about their work. It's nice if others like it, but you got to move on.

That's a big stumbling block for artists — if other people don't like it. I know artists who are very proud of their work but are very bitter about other people not liking it and not buying it. They don't feel that other people appreciate it.

What I would say to them is perseverance is the important thing. Stick with it long enough and people will come around to your way of thinking.

Have you always been that confident?

I don't know that I'd call it confidence. I don't know how to put it — maybe I'm lucky in that I did have some early success so I can talk big like this. But I just can't work any other way. I mean, I have heroes too — Lucas Samaras, Louise Nevelson, Joseph Cornell — they are three people that I have admired, at least their work; maybe not their lifestyle. But I don't think that my work is derivative of those people's work. I just happened to like the way they thought about their work.

In this current moment of time, with the crazy politics of war and such, do those outside events and politics influence your work?

I'm sure they do. It might be subliminal, but I feel really strongly about what's going on right now. I'm saddened by what's going on right now. Very much so. And that has to affect, if nothing else, the type of energy I put into a piece of work. But I guess it's true, that the artist in one way or another reflects the world around him.

When you say you're saddened, do you want to explain what you mean by that?

I think we're so wasteful. I cannot give you enough adjectives to tell you what I think is going on. But we just think that we're the answer to the world's problems and that they do what we say or tough. I just feel very strongly that the people in any other country are just like the people here.

[email protected]