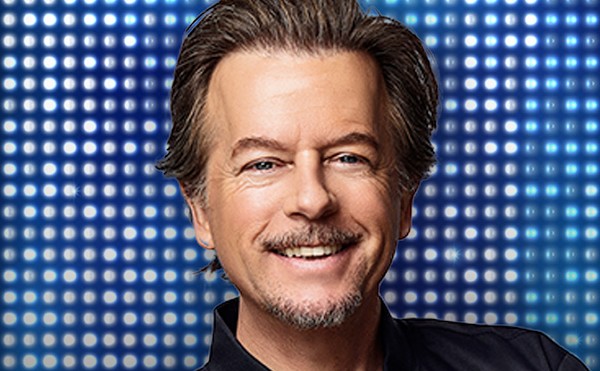

In 'Roger and Me,' director Michael Moore assailed corporate greed. In 'The Big One,' he does it again. But he doesn't work very hard

W ith the 1989 release of his shot-heard-round- the-world feature film, "Roger and Me," Michael Moore became the first dissenting voice to convey the disaster of Reaganomics to a mass audience. Documenting the economic devastation wreaked by General Motors in his hometown of Flint, Mich., Moore eagerly assumed the role of spokesman for the disenfranchised underclass.

Since then, his output has included a mostly brilliant television series, "TV Nation," and the best-selling laceration of corporate policy, "Downsize This! Random Threats from an Unarmed American." As evidenced by his second documentary feature, "The Big One," however, Moore appears in serious danger of allowing a crippling combination of ego and lack of focus to call a forfeit in his progressive ball game.

Similar to "Roger and Me" in its construction, but miles away in terms of power and purpose, "The Big One" follows Moore on his promotional tour behind "Downsize This!" as he takes time out from lectures and book signings to visit with Americans who have felt the crushing blow of the Wall Street hammer. In Centralia, Ill., he bonds with workers at a PayDay candy-bar plant, who have just been handed pink slips by a company posting a $20 million profit. On a visit to Iowa, he engages in a clandestine rendezvous with Borders book store employees desperate to unionize. And in the film's climax, he's granted an unprecedented, on-camera interview with Nike CEO Phil Knight, who breezily asserts that his com-pany has to farm its labor out to Indonesian sweatshops because "Americans don't want to make shoes."

Knight's audacity is astounding, and the encounters with the heartland's forgotten sons and daughters resonate with a particular poignancy. It's a shame, then, that such moments are outnumbered by the endless scenes of a self-satisfied Moore grinning his way through live readings of monologues lifted straight from the pages of "Downsize This!" in front of rapt audiences of college students and assorted acolytes. Despite his "man of the people" persona, Moore's willingness to rehash stale routines for a fresh paycheck puts him squarely in the company of such overpaid, multimedia comedians as Jerry Seinfeld and Paul Reiser. For someone who endlessly asserts that all America wants is a chance at an honest day's labor, he himself doesn't seem keen on having to work very hard.

On a good day, one might justify the flimflam as an attempt to bring the book's message to the huge portion of the population that finds reading anathema. The irony, however, is that "Downsize This!" wasn't all that worthy of retranslation in the first place. The book was little more than a marginally entertaining reiteration of the theme Moore first sounded in "Roger and Me": The movers and shakers of the Fortune 500, lauded as exemplars of the free-market system, are actually criminals in the strictest sense of American justice. A correct and praise-worthy message, but Moore didn't have the comedic range to carry it over the course of a full-length text. The book felt padded, and it raised suspicion that its author might only have one story in him.

The idea had been planted by "TV Nation," the series that ran as a summer replacement on both NBC and Fox. A weekly exposé of the underside of the American system, the show's success largely stemmed from segments contributed by such talented co-conspirators as Rusty Cundieff and Janeane Garafolo. In comparison, Moore's own pieces displayed a narrow vision; even though it was an amusing, challenging conceit to dress an employee in a chicken suit and send him off in search of big-business malfeasance, after a few weeks the joke just wasn't funny anymore.

At least Moore was trying to break new ground in the television medium. In "The Big One," he shows no such ambition. Worse, he's become consumed by his supposed status as a social phenomenon, and so the new film treats us to "framing" footage detailing the itinerary of his promo trek, from appearing on wacky, drive-time radio programs to flying first-class across the 50 states. This does nothing to advance Moore's stated agenda, unless we're supposed to find it somehow thrilling to watch him receive the royal treatment from the very system he's out to undermine. That scenario was obsolete about 30 years ago, when the first counterculture pop stars kidded themselves that they could take Las Vegas' money without "going Vegas" themselves. (Remember Alice Cooper playing golf with Gerald Ford?) Instead, they bought themselves a one-way ticket to irrelevance.

Moore is on a similar course. He was initially smart enough to realize that the public needs a face to go with any issue, but his obvious relish at making that face his own has blinded him to how tenuous his position actually is. "Roger and Me" worked (as a film and a title) because Moore was a relative nobody, a dumpy, powerless David going up against a high-income Goliath. The more we see of Michael Moore -- the book, the movie, the oversized T-shirt -- the more that moral ground erodes.

Moore's resume is a strong one. Most of his life has been spent supporting liberal causes, from his teen-age days on the Flint school board to his adult stewardship of alternative publications. In addition, he's used a sizable chunk of his income to offer aid to the needy whose plight has made him a household name.

Those facts are hard to keep in mind when he presents us with such self-serving, vaudeville productions as "The Big One," down-playing the pathos (and even the humor) of the downtrodden in favor of another chance to make himself the show. The end result is that even those who share Moore's outrage at anti-democratic policy are left asking: Is this guy really the best we can do?

For now, we can console ourselves that Moore's heart is in the right place. Yet his projects bear increasing resemblance to a Thanksgiving visit from a none-too-favorite great uncle, who insists on dominating the conversation with the same, musty jokes and shopworn tales of 1920s labor uprisings that we had to suffer through last time. The fact that he's usually right doesn't quell our desire for him to just pipe down for a change, and remember that there are other people in the room.

Still, we bite our tongues, and do our best to love him. For better or for worse, he's family.