We all know that recurring nightmare in which people find themselves stripped down in front of their colleagues, everything hanging out for all to see. So be sensitive to such a sense of exposure when an intimate exhibit of new art by the art faculty at Valencia Community College opens this weekend: It's a show of the educators' stripped-down inner workings. As teachers, their personal muses must remain mostly muted, so as not to unduly influence their students; but on their own time, they are unique artists in their own right.

Valencia's art department, led for more than 15 years by Michael Galletta, is a stronghold of talents. Five of them – Galletta, Camilo Velasquez, Rima Jabbur, Linda Ehmen and Jackie Otto-Miller – contributed to this year's edition of the annual exhibition.

"You have to show students more than yourself," is how Galletta describes an art teacher's basic responsibilities. His experience has taught him to remain sensitive to the power that mentors can wield over those who are developing their skills; if the former are not careful, they can spawn protégés instead of cultivating originals. Galletta feels the goal is to have an "influence of spirit" that sets an individual's skills free. And it's spirit that runs wild in the three clay horse sculptures Galletta will be displaying in the faculty exhibit. (The weekend before opening, the sculptures were still being finished in his studio, not yet fired or given their finish. That echoes Galletta's classroom policy: Make deadlines by whatever means necessary, as long as your work doesn't look like it was assembled the night before.)

The powerful animals that Galletta hand-molds exude confidence. They are more poetic in representation than perfectly proportioned: The heads are smaller, the hindquarters and hooves massive, the tails almost nonexistent. Yet there's a gentleness relayed in their poses. One beast lies on the ground, resting but alert. Two others are caught rolling about on their backs, more like dogs. Galletta admits to self-portraiture in his manipulation of equine energy, though, interestingly, he himself has never even ridden one.

Ritual is invoked in some burnt-match constructions contributed by Velasquez. His trio of enigmatic works appear to serve as memorials of a sort – tombstones, perhaps, albeit from an unknown culture. Wooden matches blackened only at the tips are painstakingly interlocked into a pattern that fills an outline on a plain white background; a few simple sentences help to unlock the mystery to the viewer. In particular, the final words that complete the piece "In Their Memory" – wherein the charred sticks are shaped into a cross – help to explain the emotional nature of the Colombian-born artist's tributes.

"I have no other way of letting those who have passed through my life know that they have not been forgotten," he says. "And in their memory, I have created this ritual of lighting a candle and saving the matches."

A glimpse into another dimension is sparked by Rima Jabbur's painted portraits. She's a serious student of Norwegian artist Odd Nerdrum (she studied with him in Oslo in 2002), considered one of the greatest painters of the century and praised for a tonal technique that's reminiscent of the 17th-century masters. Jabbur shares Nerdrum's rich but limited palette, which eschews color in favor of value. "He believes it's all about light and luminosity," she says.

As with many of Jabbur's works, the painting "Surfacing" was inspired by a real-life vision – in this case, the sight of a friend's daughter peacefully asleep in her car seat. "The image looked like she was coming up for air, and at the same time somewhere between waking and sleeping," the artist recalls. "'Surfacing,'" she says, "is perhaps less of a portrait than a state of mind – I kind of use her `as` a vehicle for something I wanted to put across," Jabbur explains.

For the similarly insightful work titled "Girl Looking Inward," Jabbur used a student as her source – a young woman who appears somewhat aristocratic in profile and bearing without any trappings to further the suggestion. "What I read into her, I was able to put across in the painting. She has this demeanor that is so rarefied – and that was what I wanted to paint."

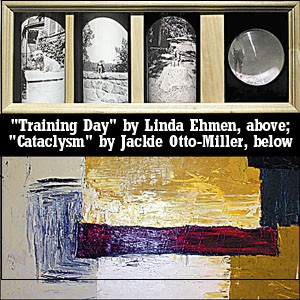

In this faculty collective, Linda Ehmen provides the photographic component. An obsession with other families' snapshots – which she's hunted feverishly at garage sales for years – is recycled into her photo-box constructions. As Ehmen has found, certain patterns and common poses come to the fore after one looks at hundreds of documentations of mundane experiences – like buying a new car, graduating from school and showing off the dog. In devising "Training Day," she says, "what I found was `that` all these people would put their dogs on some kind of stump or riser and photograph them." Through careful appointment, digital manipulation and added extras – such as the use of a magnifying Fresnel lens – she reframes the ordinary, "not very exciting" images according to her own point of view.

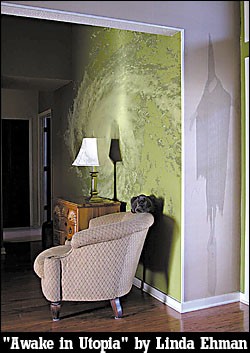

The native New Yorker's command of current events is similarly burned into a series of digital images that tie together her own cozy home – where she peered through boarded-up windows during the recent spate of hurricanes – with her concerns about the state of world affairs (a preoccupation heightened by the 2004 presidential election). Buried in "Awake in Utopia" is a gruesome shadow of a prisoner and of an all-too-familiar weather-map spiral.

Rounding out the differing styles and media represented in the show are abstract paintings by Jackie Otto-Miller, whose work is so personal that she rarely shows it to students. Abstractions, she says in a teacherly manner, challenge the viewer, demanding an individual impression rather than a direct connection with the artist's particular vision. In the body of work Otto-Miller shares here, the objects on her canvases are mostly geometrical forms, as opposed to gestural as have populated some of her previous works. Design is her specialty, and her juxtaposition of colors and shapes references the architecture of nature. She also lays down layers of paint and wax and more paint, and then scrapes through the layers and builds up again – an echo of our constant state of degradation and rebuilding.

In "Cataclysm," Otto-Miller interprets a winter she remembers from her youth up north – specifically, the disturbing sight of snow melting on the tracks as she was riding on a train. The colors she employs are determined by her memories: The long stretch of a red-toned "track," as it were, links shape to shape, color to color, all coming together without a loss of individual distinction. When gazing upon the compositions, "It's a journey of the eye," the painter says. "It's a thing of sense."