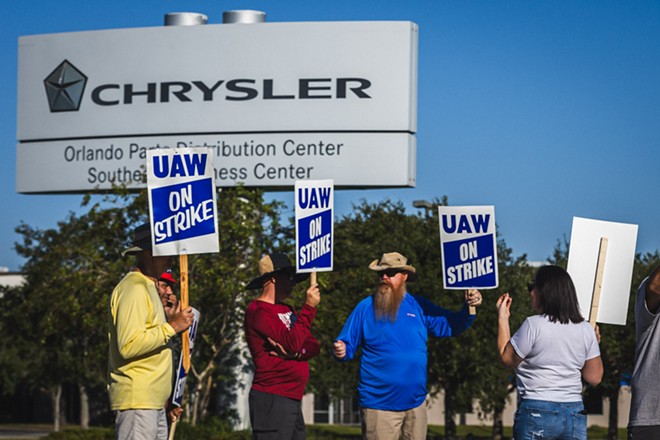

On strike is the last place he and many of his co-workers at the old Chrysler auto parts center in Orlando want to be, collecting $500 per week from their union in strike pay and waiting for their employer to negotiate a new labor contract with their union that satisfies the demands of its members.

That union, the United Auto Workers, is fighting for a new four-year contract that meaningfully attempts to make good on promises that Chrysler, General Motors and Ford made to their union employees over a decade ago. That's when those employees took concessions like wage freezes and the end of cost-of-living adjustments — concessions that helped ensure their employers’ survival.

“We’re not out here just for our cause,” Lopez told Orlando Weekly early Friday afternoon, sitting outside of the parts depot he’s worked at for 20 years, after transferring from a Chrysler plant in Indiana that was sold to manufacturing company Metaldyne in 2003.

Lopez, who plays guitar in his off-time and often travels back to his home state, emphasized that this strike is bigger than just himself or his co-workers.

Organized labor pushed for rights that many of us take for granted today: a minimum wage, a 40-hour work week, and the right for most workers to organize for better pay and working conditions. Gains made by unions set standards for non-union workplaces industry-wide, placing pressure on other companies to offer incentives, lest they lose their competitive edge in recruiting and retaining workers.

That’s why, for Lopez, “We’re out here for the cause of everybody.”

Chrysler workers in Orlando have been on strike for a full month, after they and about 5,600 other members of the United Auto Workers in Stellantis and General Motors auto parts centers walked off the job Sept. 22, joining over 13,000 others already on strike at three assembly plants in Michigan, Ohio and Missouri. Thousands of workers at Ford's most lucrative plant in Kentucky also joined the strike last week, in a surprise call to action from union leadership, while Big Three workers who are not on strike are refusing to work voluntary overtime.

It's the first strike against all of the Big Three automakers simultaneously in the union's history. Instead of all 146,000 UAW members of the Big Three striking at once, the union's taken a staggered approach, calling on workers to join the strike at little more than a moment's notice in order to keep the companies guessing.

The auto workers’ strike, in a return to the UAW’s militant roots, is a broad call to end corporate greed both in the auto industry — where the Big Three alone have amassed nearly a quarter-trillion dollars combined over the past decade — and beyond, as CEO pay in recent decades has soared off the backs of the working people who make their companies profitable.

Stellantis, the most profitable of the Big Three auto companies, reported $12 billion in net profits in the first six months of 2023 alone, up 37 percent year over year. The company, which also sells popular brands such as Dodge and Jeep, executed another $500 million in stock buybacks just days ahead of the strike, yet pleads poverty when called upon to meet the union’s demands for double-digit percentage raises (to make up for concessions made to save Chrysler during the 2008 financial crisis).

The average hourly wage of U.S. auto manufacturing workers has declined 30% since 2003, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Workers at the Stellantis depot centers start at around $16 an hour, and top out at $32 an hour.

During negotiations, Stellantis has offered a 23% increase to base pay over four and a half years for workers. The union says that’s not good enough — they’re fighting for 36%, to nearly match the average raises given to the Big Three’s CEOs.According to the UAW, Stellantis has also dragged its feet on agreeing to other demands regarding job security, COLA, retiree pay and a just transition to electric vehicle manufacturing.

So far Stellantis, based in the Netherlands, has agreed to eliminate a divisive wage tier between longtime “legacy” workers and newer hires. They’ve agreed to establish a minimum $20 per hour pay for temporary workers (who can work for years before getting a chance to apply for a permanent position), to create 1,000 permanent positions for current temps, and to give workers the right to strike over plant closures — an economically devastating outcome for small towns like New Castle, Indiana, that more than a handful of workers in Orlando understand intimately, after living through it themselves.

“We’re just asking for a fair agreement,” said Lopez told Orlando Weekly that first day he and his co-workers walked out of the parts depot. They haven’t been back inside since.

Workers at Orlando’s Stellantis center, off Boggy Creek road near the Orlando International Airport, last went on strike in 2007. But that work stoppage, under different union leadership, lasted just six hours — not even long enough for workers on the second shift to join in, several longtime employees told Orlando Weekly.Most of the Big Three automakers’ assembly plants are concentrated in the U.S. Midwest, but their parts distribution centers — where workers store, organize and prepare parts for dealerships — are scattered all over the country.

Stellantis workers in Orlando are the only Big Three workers on strike for hundreds of miles, although UAW-represented workers of Mack Trucks, the parent company of Volvo, have also walked off the job and have been on strike since Oct. 9 in a separate labor action up in Jacksonville, Florida, and in two other states after rejecting a tentative deal that workers felt was insufficient.

“I’m inspired to see UAW members at Mack Trucks holding out for a better deal, and ready to stand up and walk off the job to win it,” said UAW President Shawn Fain in a statement. “The members have the final say, and it’s their solidarity and organization that will win a fair contract at Mack.”“Everything we do is in service of building the strength of our membership and building a better future for UAW members and the entire working class”

tweet this

Stellantis, the most profitable of the Big Three auto companies, has resorted to playing dirty, despite coming to the bargaining table with some concessions over the last month.

As The Intercept first reported, the company recently began recruiting volunteer replacement workers from its Business Resource Groups to staff parts distribution centers.

General Motors has also reportedly brought in scabs (a term which can refer to nonunion workers or to union members who cross the picket line to perform labor usually done by the workers on strike).Lopez, from the Orlando parts center, said Stellantis recently called in salaried managers from across the region to work in their facility, beginning this past Monday.

One manager was allegedly told to operate equipment she wasn’t trained to use, and quit her job at the center during the first week, before other regional managers were called in. She drove out of the parking lot “like a bat out of hell,” according to one worker Orlando Weekly spoke to.“Now that they're getting a taste of actually physically doing our jobs, I think they're singing a different song,” said Lopez.

Inside the parts depot, workers are trained to use equipment like forklifts and stackers, a fork truck that workers use to pick up things like engines and transmissions, often with six or eight engines placed on a pallet. “[It’s] a dangerous job,” said Chuck Cowell, another worker on the picket line Friday who trains people how to use the equipment.

“They’re [Stellantis] violating their own health and safety policy because none of them [the managers] are licensed to actually be on equipment,” Cowell added.

Just yesterday, More Perfect Union first reported that Stellantis has also deployed security guards from notorious strikebreaking firm Huffmaster to multiple parts distribution centers — a service that doesn’t appear to come cheap. A 2021 tax filing from Mercy Hospital in Buffalo, New York, shows the nonprofit hospital paid Huffmaster a whopping $62,626,022 for “healthcare staffing services.”

That fiasco was messy enough to get the attention of New York State’s Attorney General, who wrote a “cease and desist” letter to the hospital, noting that Huffmaster was performing unlicensed activity.

Historically, strike actions have helped leverage workers’ demands for basic dignity, workplace protections, and the ability to have a voice on the job. Strikes by workers in other industries have recently won major gains.

After a five-month strike, over 11,000 film and television screenwriters organized with the Writers Guild of America won higher pay, better streaming residuals (essentially, royalties), and regulations on the use of artificial intelligence to help prevent labor cuts in their own new contract — while actors and performers with SAG-AFTRA remain on strike.

“They want fear. They want uncertainty. And what we have is our solidarity.”

tweet this

More than 75,000 workers for the Kaiser Permanente healthcare system reached a tentative agreement after a three-day walkout earlier this month that will deliver 21% raises over four years and help address staffing shortages, if approved by union members.

UPS workers organized with the Teamsters, including delivery drivers and warehouse workers, reached a “historic” contract ahead of their August strike deadline, delivering more full-time job positions, a $21 minimum wage for part-timers (who’d often been left behind in contracts negotiated by former union leadership), as well as important worker protections such as air conditioning and cargo ventilation in package delivery trucks.

Similarly, a strike threat by food service workers at the Orange County Convention Center also won a $5 raise for the lowest-paid workers this year (plus general raises for others) and a pension — a rarity in this day and age. Disney workers this year similarly won gains, albeit without a strike threat.

Last year alone, the country saw over 400 work stoppages involving approximately 224,000 workers over demands such as pay, health and safety, staffing, and job security, according to Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker.

Researchers from the university’s school of Industrial and Labor Relations found that the majority of work stoppages occurred in the accommodation and food service sectors, while the majority of workers on the picket line worked in the educational services industry.

“Everything we do is in service of building the strength of our membership and building a better future for UAW members and the entire working class,” UAW president Shawn Fain said in a bargaining update Friday.Cowell told Orlando Weekly that he and his co-workers appreciate the members of the public who’ve come out to stand with them, drop off cases of water and food, and to show them others in the state have their backs. That goes too for members of other unions who've shown up to the line, from nurses, to teachers, Disney World workers, UPS workers, and most recently a small group of flight attendants.

Fewer people have come out the longer the strike has gone on, however. Lopez recalled some guy driving a Tesla stopping by, dropping off a box of donuts. A handful of politicians, community organizations like the Central Florida Jobs with Justice and the Democratic Socialists of America, and other socialist organizations have also shown up to the line in solidarity.As an Orlando Weekly reporter left the scene Friday, an Amazon semi-truck driving by the picket line honked their horn in a show of support.

“The bottom line is, we've got cards left to play, and they've got money left to spend,” Fain said of the Big Three. “They want fear. They want uncertainty. And what we have is our solidarity.”

Subscribe to Orlando Weekly newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | or sign up for our RSS Feed