"I've been tried, and it's time to quit. It's getting old."

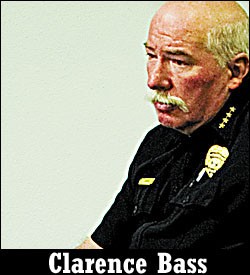

And so, with a forced smile barely hiding a look of annoyance, Edgewood police Chief Clarence L. Bass abruptly ends a 30-minute interview. Heavyset, mustached and bald, Bass is imposing in an unintentional way. There's weariness to his demeanor, underscoring the fact that he doesn't like his 11-member police department being the focal point of a controversy that has divided this city of approximately 2,000 people.

He's tired of explaining himself. He's tired of being called a liar and a bully. He's tired of the media questioning him. He's tired of city council members trying to fire him. Bass, 61, wants all this over with so he can do his job for two more years, then retire. "I haven't done anything wrong," he insists.

Without the police department, there'd be little reason for the city of Edgewood to exist. It takes up more than half the city's budget. The city's biggest infrastructure development in memory is the $395,000 police building that opened in 2002 adjacent to city hall on LaRue Avenue.

But in the last six months, Bass has once again come under fire. His detractors say Bass is a good ol' boy who likes things done his way, and is willing to bend the rules – or the truth – to get what he wants. Bass is not without his supporters in Edgewood, however, and they contend that his recent troubles are nothing more than a continuing vendetta that began in 1999 when a former mayor tried, and failed, to get rid of Bass.

"My problem is, nobody wants to know the truth, nobody cares about the truth," the emabttled chief says. "This has been going on for 10 years. They keep saying stuff. Every time I talk to somebody, it gets worse. It keeps getting fostered and fostered. The harm has been to the police department and the citizens who had to pay all this money. I don't trust anybody."

The city put Bass on administrative leave Aug. 3, though Mayor Diane D'Aurora reactivated him on Aug. 17, citing a post-hurricane emergency. In October, the city formally hired John McCollister, a Port Orange arbitrator, to investigate claims against Bass. McCollister's report, delivered to the council on Dec. 7, cleared Bass of any wrongdoing.

But McCollister's report isn't likely to be the last word. "I believed this investigation was truly going to be an investigation," says city council member Judy Beardslee, who along with her husband, Edgewood police officer Ron Beardslee, has been among Bass' biggest critics. "`But` there was no finding of facts. It was all judgments of McCollister … . We didn't make a decision `on whether or not to keep Bass`. No one's even discussed it yet."

LEGENDARY SHOT

Bass had a typical Central Florida upbringing. His father owned a floor-refurbishing business. His mother was the business' bookkeeper. Raised as a Baptist, he had just started attending Catholic church when he was hired by Edgewood in 1993. An average student – he made Cs and Ds in high school – Bass preferred hunting and fishing to academics. He graduated from Colonial High School and joined the Army, where he served from 1962 to 1965. He came home and worked with his father for three years, before joining the Orlando Police Department in 1968.

He pursued a criminal justice degree at what was then called Valencia Junior College, though he only got half of the credits needed to graduate.

His OPD record was exemplary, if overzealous, according to his personnel file and media reports. In 1970 he shot at or near three suspects in five months; all the shootings were ruled legal, though a review board questioned the practicality of one incident. In 1979, he received an award of valor for persuading an armed-robbery suspect who was holding a hostage to drop his gun. Three months later he got a merit award for shooting and wounding a robbery suspect while at an off-duty security job. In 1972, and again in 1979, the Orlando Jaycees declared him "officer of the year."

During his tenure at OPD, Bass served as a road cop, a K-9 officer, an undercover drug officer, a criminal investigator, a police instructor and a traffic homicide investigator. In 1982 he injured his back and ankles in an on-the-job motorcycle accident.

Shortly before his retirement in 1989, Bass, who lives in Kissimmee, shot and wounded a neighbor. He told Osceola County deputies that the man was shooting at him, according to an Orlando Sentinel story. The OPD criticized Bass for improper use of force, but no charges were filed. Bass says today that the neighbor was using houses in the neighborhood as target practice, and that his shot was in self-defense.

John Park, president of the Central Florida Police Benevolent Association, calls Bass' shot – 300 yards with a 9 mm handgun – "legendary," and says it's still talked about in the police academy.

"That's just a joke," Bass says.

After leaving OPD, Bass spent four years as a police union negotiator, working with municipalities across the region. In 1992, he ran for Osceola County sheriff, but placed third in the Republican primary. In 1993, then-Edgewood mayor Richard Brinkman asked him to apply for the vacant police chief position. He beat out 25 other applicants for the job.

"It was a chance for me to do the job my way," Bass says. "Here I've been telling chiefs for 20-something years how they did it wrong as a PBA `Police Benevolent Association` person."

The department Bass inherited was a mess. Officers had to buy their own guns, holsters, uniforms and badges. For his first two years, Bass didn't have a city car; he used his own car for work and didn't ask to be reimbursed for mileage. The police building was so small that it had one unisex bathroom, and the storage room doubled as an evidence room.

"When I came here, there was chicken wire separating the prisoners from the police officers in police cars," Bass says. "There was no formal training; the guys bought their own leather and gear."

He pressed city council and got his officers better equipment and pay. The city opened its new police building in 2002. And though there have been complaints about the quality of training Edgewood's cops receive, the situation is better than it was 12 years ago.

GRUMBLING IN THE RANKS

The strongest allegations against Bass come from an anonymous survey the PBA conducted of Edgewood cops in June. Six officers (of the eight who are PBA members) responded to the survey, and all agreed that morale in the department was low or very low, and advancement opportunities were poor. Five said that they couldn't file grievances without repercussions, that personnel rules weren't applied fairly, and that the department was rife with favoritism.

In the survey's comments section, one officer wrote, "Officers constantly are enduring a hostile work area. If you have an opinion or concern the lieutenant would instantly assume and state that you have a bad attitude." Another wrote, "The department (administration) induces fear and intimidation into the officers." A third cop wrote, "Morale is at an all-time low, I doubt that any current patrol officer will be working here by this time next year. When the officers tried to talk as a group to Chief Bass and Lieutenant (now Sergeant John) Freeburg we were told by chief that the Edgewood police department 'was an absolute dictatorship and he was in charge.'"

After months of having the issue dominate city meetings, the council decided to act. Bass accepted administrative leave in August, and the council (over the objections of D'Aurora) agreed to conduct an investigation. Unlike in 1999, when then-mayor Jim Muszynski acted as the investigator, the city decided, given D'Aurora's outspoken support for Bass, to hire an outsider. The PBA and Bass both agreed on McCollister, and agreed to pay him $4,200.

Two of the city's five council members voted against the investigation, and then against funding it. Under Edgewood's weak-mayor form of government, D'Aurora didn't get a vote.

BAD LIEUTENANT

On Oct. 28, 2003, Bass promoted Sgt. John Freeburg to lieutenant, his second-in-command. This move became controversial after allegations that Freeburg used abusive and racist language and berated his underlings. Officer Ron Beardslee says he complained to the chief about Freeburg's language before the promotion, but Bass made the move anyway.

Following the PBA survey in June, D'Aurora announced she had conducted her own interviews with the city's cops, though she didn't publish the results or take notes. Based on that, and in consultation with Bass, Freeburg was demoted back to sergeant in July.

"Your dedication to the city of Edgewood and the Edgewood Police Department has never been questioned," Bass wrote in a demotion memo included in Freeburg's file. "I personally have counseled you on more than one occasion concerning your use of language and there is no excuse for a manager or a supervisor to use such language."

But Bass signed and dated the demotion memo after Freeburg himself resigned his job as a lieutenant July 16, raising a question about timing of the incident.

In any case, Bass says he's never tolerated racist language in his department. "In the 12 years I've been associated with the city, I've never used a racial term," Bass tells Orlando Weekly. "Nobody here has used a racial slur. Nobody. Now who's lying?"

That's not what McCollister concluded in his investigation of the department, however. "Further investigation revealed that alleged racial slurs were not made by the chief, but by one of his officers. Everybody in the department with whom the investigator spoke agreed with that." Also, at the Dec. 7 council meeting, McCollister said, "I'd rather not go into details in this, but one of the officers admitted he `used racist language`."

During the Jan. 4 meeting, D'Aurora insisted that McCollister's report was misquoted, and that no Edgewood officer admitted to using racial slurs. Instead, she said, McCollister's report meant that an officer was accused – but never admitted to – using slurs. The chief was never accused, she asserted.

The chief could indeed be coarse. Several current and former officers interviewed for this story say Bass would occasionally grab his crotch during meetings and boast about having "the biggest balls in town." PBA president Park says he saw Bass do just that at a contract negotiation meeting earlier in 2004.

"He would say things; he walked into a meeting and grabbed himself and said, 'I'm king around here, I'm God around here," says former officer Julie Szelengiewicz.

Szelengiewicz's case is at the center of the latest investigation into Bass' job performance. Bass told the council – which has the authority to fire police officers at his recommendation – that she had resigned. That was a surprise to Szelengiewicz, however, because she asked Bass to fire her due to a medical condition that kept her from working. If she was fired, she'd be able to continue her medical insurance; if she resigned, she wouldn't.

Edgewood city council members Paige Teague and Judy Beardslee say Bass lied about Szelengiewicz' resignation. They also say he lied about the sale of two police vehicles. On March 16, the first meeting of the newly elected city council, Bass received permission to trade in two old police cars for a 2004 Ford Crown Victoria, valued at $24,599. The two cars had a combined trade-in value of $4,750, Bass told the council, meaning the council would have to ante up $20,000 for the new car, which it did.

But Bass didn't trade the cars in. Instead he told the council later that the cars would be sold at auction. That didn't happen either. Instead, on May 21, a towing company named RSC, Inc. wrote the city a check for $4,800 to buy the two cars. Bass told the council he thought RSC was going to auction the cars off.

That same day, May 21, RSC wrote a $900 check to the police department's building fund. Four days before that, RSC had donated $500 to the fund.

Prior to RSC's donations, Teague says she demanded that Bass show the council a list of all contributions and receipts from the building fund. City records show the building fund was running a $5,196 deficit before RSC's donations which, along with the money generated from selling the cop cars, put the building fund in the black. (City council later forced Bass to take the proceeds from selling the cars back out of the account.)

In McCollister's opinion, it was a case of no harm, no foul. "This investigator found no evidence of the chief deliberately lying in any way as an attempt to harm the city."

Others aren't so sure. "There's no way Bass thought they were going to be sold at auction," says Judy Beardslee, who believes the cars were worth almost twice what Bass sold them for. "We lost four thousand total on both of them, maybe more. We lost money on that deal."

TURNING SOUR

For his first five years as police chief, Bass had few problems with the city council. The trouble started in 1998 with a payroll error; Bass blamed the discrepancies on bad math.

Then, in October 1998, the city reached a deal with the state Department of Environmental Protection to avoid a $1,600 fine for the police department's illegal disposal of toxic waste in 1995. That year, an underground gas tank was allegedly buried in a department employee's backyard. Though the DEP had been investigating the illegal dumping allegation for at least a year, Bass never bothered to tell the council. Under the terms of the 1998 agreement, the city admitted neither guilt nor innocence, but did agree to establish a hazardous-waste disposal workshop for other agencies.

In 1999, things came to a head when Muszynski – citing high turnover and low morale – placed Bass on leave and asked the council to fire him. Muszynski's allegations echo recent charges against Bass: dictatorial management style, ignoring the mayor's orders, butting into city business outside the police department and misleading city officials.

Muszynski also made a more striking allegation. On March 24, 1999, Bass gave a sworn statement that he had destroyed seized narcotics at the police compound the day before. What really happened, according to a written statement from one of Bass' sergeants, was that Bass had taken the drugs to his house in Kissimmee and destroyed them there, with two fellow officers as witnesses. In Muszynski's mind, that equaled perjury.

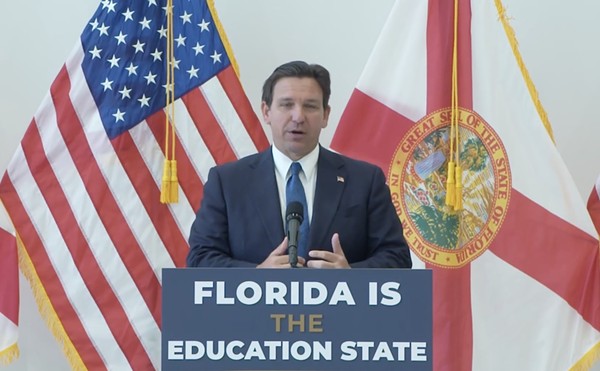

The city council sided with Bass. After a nine-hour just cause hearing on July 29, 1999, it voted 4-1 to keep the chief. Muszynski didn't give up. He asked the state attorney's office to investigate the perjury allegation. It declined. He then asked the Gov. Jeb Bush to appoint a special investigator. Bush did, but that investigator found no evidence of wrongdoing. Muszynski asked the governor for another investigation, but Bush declined.

The next year, two city council incumbents were voted out, blaming Muszynski's scrap with Bass for their defeat. One of the new council members was Bass' attorney, William Sheaffer, who became council president and immediately stripped the mayor of some of his duties. Muszynski didn't seek re-election two years later.

Bass won the war.

BATTLE ON

A former Lutheran minister turned arbitrator, McCollister was the only investigator to respond to the city's Aug. 6 request for someone to investigate recent allegations of wrongdoing against the chief. His résumé lists 48 mediation hearings, mainly between municipalities and unions. In 35 percent of cases, he boasts, he led "both sides in reaching a compromise that is in the best interest of both a municipality and grievant." He wanted $70 an hour for his work, and eventually sent the city a bill for $3,155.97, less than the $4,200 the city had budgeted for the investigation.

During his investigation, McCollister spoke to 60 witnesses, most of whom he spent 30 minutes or less with. He took no sworn statements. He didn't record his interviews, or delve into public records. Some interviewees say he spent 15 minutes or more of interview time talking about his short-lived baseball career.

McCollister declined to talk about his report. "One of the things I've asked people to do is not talk to the media," he says.

Bass' enemies have no such reservations, and say McCollister did a lackluster job. "With my situation, `McCollister` wanted to talk the first few minutes about my family," Judy Beardslee says. "Three times I asked him to refocus on the matter at hand."

When McCollister gave his Dec. 7 report, it looked like Bass had again dodged the bullet. McCollister declared that, though the chief could be "gruff," there was no evidence of wrongdoing. If Bass ruled like a dictator, McCollister wrote, "This comes as no surprise to anyone who is aware of police procedure. A department of law enforcement is often a paramilitary structure in which the chief's word is final. It is not a democratic organization."

Regarding allegations that Bass lied to city council, and bent the law to get things done, McCollister decided that the chief's heart was in the right place. "The baseball icon, Branch Rickey, used to call such action 'errors of enthusiasm,'" McCollister wrote.

He concluded that charges of intimidation were subject to interpretation, and rejected the PBA survey because it was anonymous. He wondered why, if things were so bad, Edgewood police officers had only filed "one or two" grievances in the last five years. (Answer, according to Park of the PBA: fear of retaliation.)

Other than a few recommendations urging Bass to be nicer and the city to be clearer on how it could fire the chief, McCollister had little criticism of the chief. He thought it was time for everyone to just get along.

It wasn't what Bass' critics had in mind. "The RFP was specific," Judy Beardslee says. "We requested an investigation, not an arbitration, not a mediation, not fluff."

(Bass-haters did come away with one upshot from McCollister's report: Previously, the city attorney had ruled that the city council could vote to fire Bass only on the mayor's recommendation. Given D'Aurora's ties to Bass, that isn't likely to happen. McCollister found that the city charter was unclear on the issue, which meant that the city council could call for a just cause hearing to fire him.)

Council president Teague was so displeased that she asked that the council debate whether or not they should pay McCollister. "I have a real problem paying him," Teague told her colleagues. "I don't think he did the job we wanted him to do. I don't think we got what we asked for."

Teague faults McCollister for not taking sworn statements, which city attorney Virginia Cassady believes the contract required him to do.

Whether or not to pay McCollister is already a moot point, however. City clerk Fay Craig already mailed the check, even though Teague sent her an e-mail before Christmas requesting that she put the issue on the city council agenda. Craig said at the Jan. 4 meeting that she thought the check had gone out before Teague made her request. Later, Craig told the Orlando Sentinel that Teague never specifically directed her not to pay.

After delivering his report to the city council in December, McCollister wrote the police department a $350 check to buy new gloves.

PRO BASS

Bass has his fans. "I think the chief has done a good job for the city," council member Nancy Crowell says. "The residents like him. I think he always tells the truth to the best of his ability."

"I'm a supporter of everything that's good for Edgewood," says former council member J.T. Blanton. "I spent a lot of time in that police department. I never saw anything untoward. I was there a lot. It was always polite, respectful. I never saw anything resembling what `critics` said. ... I hope this thing, that some of the people listen to what Dr. McCollister said. Some of this stuff is counterproductive. I think the majority of the council is willing to do that."

Bass isn't so sure. "There are certain individuals that are not going to let this die."

Namely, Muszynski. "Muszynski is a negative person who thinks everybody involved in the city, everybody is doing everything underhanded," Bass says. "He corrupts everything that's going on."

Sheaffer, Bass' attorney, also blames the former mayor. "He had done a lot of good for the city of Edgewood," Sheaffer says. "`At some point`, Jim – in my opinion – lost sight of what was in the best interest of Edgewood. His ties to Clarence Bass became strained. He and `former council member and Bass critic` Shirl Worthen felt they needed to get rid of Chief Bass. It was more personal than professional."

Sheaffer, who didn't run for re-election in 2002, says Muszynski now has a sympathetic ear with council members Teague and Beardslee. Just like 1999, he says, when the city's investigation didn't produce the desired result, Bass' critics won't let it go.

"The only way they can get Bass out is to get a person in the mayor's position who is critical of Bass `in March's elections` and would bring a just cause hearing," Sheaffer says. If that happened, they would still need three votes to oust him – and now, only Beardslee and Teague seem determined to oust him. And even then, Sheaffer says, "The first thing I would do is march into circuit court with a history of this, two investigations `that cleared him`. It would never be sustained in circuit court."

LEGACY

I ask Bass what he wants to be remembered for. He pauses, and for a moment, the discomfort of an otherwise tense interview is gone.

He talks about his accomplishments: boosting staffing, getting better pay and equipment, the new building. And then he talks about the one thing he still wants, accreditation – the Florida Department of Law Enforcement's stamp of approval that the Edgewood police department is up to snuff.

"I think we would have been an accredited organization already if this stuff had not been done," Bass says. "It's something that the citizens can know, that there has been an outside professional organization to come in here and do inspections and go through the books and make sure what we are doing is right according to the standards that are out there."

Then I ask about his legacy. "Professional policies and procedures that are accredited, a building everybody can be proud of. Like when McCollister was riding around, everybody was telling him how great the department was."

And then, one last defense: "I haven't done anything wrong."