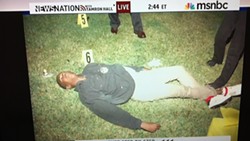

Trayvon Martin, after his encounter with George Zimmerman. (From Gawker.)

One hundred and forty-two years later, an armed white man deemed an unarmed black teenager suspicious, and decided to follow him. There was an altercation, and the unarmed black teenager ended up lying on the grass, still, eyes open, a bullet through his chest, dead. And just last night, a jury in Sanford, Florida – an area that, like Mississippi, has a long, dark racist history – declared that man not guilty.

That doesn’t seem like progress.

Race relations in this country have never charted a linear course, Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous line about the arc of the moral universe bending toward justice notwithstanding. The tepid reconciliation of the Reconstruction era gave way to Northern indifference in the late 19th century, while the South reverted to subjugating blacks wherever it could. The election of Woodrow Wilson, a fierce, avowed racist who purged the government of African Americans, led in part to the second rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. It would take another four decades and a lot of blood for blacks to gain – on paper, anyway – full and equal rights. That was 50 years ago. Indeed, just a few weeks back the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act, which it deemed no longer necessary because, as Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “our country has changed.”

And yet here we are again. Not since O.J. Simpson has a murder trial so divided America along racial lines. That division – more interesting in many ways than the George Zimmerman case itself – has underscored the very different experiences and perspectives of white and black America, and demonstrated how the scaffolding of white privilege still determines the prism through which we view current events.

Take the many instances of supposed white aggrievement this case elicited, as if Zimmerman (and by extension, all good, God-fearing, gun-carrying white folks) were somehow the victim of a racist black bloodlust. There was, for example, Trayvon’s use of the words “creepy-ass cracker” to describe Zimmerman shortly before his death, which culminated in the surreal CNN panel debate “N-Word vs. Cracker: Which is Worse?” (Hint: It’s the one you can’t spell on television.) There were the right-wingers, always eager to prove that Blacks Are The Real Racists, who predicted race riots in the event of a Zimmerman acquittal. There was the elation of white conservatives across the Internet to the verdict – “Hallelujah!” tweeted Ann Coulter; “Liberal denied vengeance. Race card came up snake eyes,” tweeted the Washington Post’s Jen Rubin – as if the consequence-free killing of an unarmed teenager were something to celebrate.

More insidiously, there were the efforts of George Zimmerman’s defense team to drag Trayvon’s corpse through the gutter, to portray him as just another young, black thug who was all about guns and drugs and gold teeth and fighting and probably had it coming anyway. During one exchange in the trial – which, admittedly, I watched only in spurts – the defense asserted that Zimmerman was justified in his suspicions of Trayvon because another young black man had been arrested a few weeks earlier for burglarizing a house in the neighborhood. (This, I presume, is the they-all-act-alike defense.) Then the defense suggested that the presence of a piece of broken awning found near the crime scene a week later indicated that Trayvon may indeed have been about to break into houses, had he not been stopped by the hero George Zimmerman.

Even after the verdict, George Zimmerman’s brother went on CNN and said he wants to know, in so many words, if Trayvon was growing drugs, buying guns and “looking to make lean.” (He also worried, because he has no sense of irony, that vigilantes would try to “take the law into their own hands.”) Then there was Zimmerman attorney Mark O’Mara’s statement, in the course of his smug victory-lap press conference: “Things would have been different if George Zimmerman was black because he never would have been charged with a crime.”

That’s not just stunningly tone-deaf. It’s empirically wrong. Consider the black single mother in Jacksonville who was sentenced last year to 20 years for firing a warning shot during a confrontation with her allegedly abusive husband. (The same prosecutor, Angela Corey, oversaw both this and the Zimmerman case.) Or Trevor Dooley, a black man sentenced to eight years for manslaughter in a case that eerily parallels Zimmerman’s: Dooley instigated the confrontation, there was a scuffle, and Dooley claimed self-defense when his white victim, David James, got the upper hand.

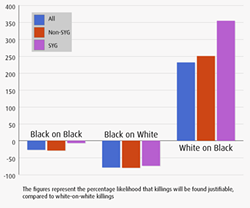

The nationwide data, moreover, tell us that white-on-black shootings are much more likely to be deemed justified than white-on-white, black-on-black or (especially) black-on-white shootings.

“Justified” shootings, by racial breakdown

The victim’s race plays a role no matter the shooter’s. Last year, in its blockbuster investigation of the state’s Stand Your Ground law, the Tampa Bay Times reported:

Defendants claiming “stand your ground” [in Florida] are more likely to prevail if the victim is black. Seventy-three percent of those who killed a black person faced no penalty compared to 59 percent of those who killed a white.

Imagine for a second the races were reversed here. A black man deems a white teenager suspicious, follows him against police advice, shoots and kills him, and claims self-defense. Is there any chance the cops would believe him, or that he wouldn’t have found himself in handcuffs that night? Is there any chance this black neighborhood watchman would become a cause celebre on Fox News? Is there any chance that crowds of white people would show up at the courthouse, claiming him as a Second Amendment champion? Is there any chance he would have gotten away with it?

Whether we like it or not, race does permeate this case, just as race permeates our entire criminal justice system, whether George Zimmerman is “racist” or not.

If you look at the forest, not the trees, the jury’s verdict last night is almost unimaginable: an armed man stalks and kills an unarmed boy. Open and closed, right? But those trees – the details – are where these cases get decided, and the law in Florida puts the burden on the state to prove the defendant wasn’t acting in self-defense, rather than forcing the defendant to prove the shooting was justified. And so on the verdict itself, I find myself in agreement with The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coats:

I think the jury basically got it right.The idea that Zimmerman got out the car to check the street signs, was ambushed by 17-year old kid with no violent history who told him he “you’re going to die tonight” strikes me as very implausible. It strikes me as much more plausible that Martin was being followed by a strange person, that the following resulted in a confrontation, that Martin was getting the best of Zimmerman in the confrontation, and Zimmerman then shot him. But I didn't see the confrontation. No one else really saw the confrontation. Except George Zimmerman. I’m not even clear that situation I outlined would result in conviction.

I think the message of this episode is unfortunate. By Florida law, in any violent confrontation ending in a disputed act of lethal self-defense, without eyewitnesses, the advantage goes to the living.

To this I would only add that throughout the past year and a half, Seminole County’s law enforcement apparatus has not acquitted itself especially well. From the cops to the prosecutors to even the medical examiner, they fumbled their way through, struggling to piece together a coherent case, even if they wanted to (the cops didn’t strike me as all that interested). Maybe prosecutors didn’t have much to work with, or maybe “reasonable doubt” was too high a mountain to climb. But they didn’t do Trayvon any favors – and certainly their work didn’t justify Angela Corey’s weird, all-smiles press conference after the state’s defeat. (That she reportedly talked to the media before Trayvon’s family only made it more off-putting.)

You should all go read this blog by Dan Gelber, a former Democratic state lawmaker, about how the Stand Your Ground law directly led to Zimmerman’s acquittal, and has basically made the state of Florida the Wild West.

While in the Florida legislature I strongly opposed the Stand Your Ground law because I believed it would provide defenses to people who had created the scenarios they sought protection from. Or it would leave juries without the proper rules of engagement that ought govern predictable human interactions.By taking away from the jury the simple notion that people have an obligation to “avoid the danger” or retreat if they could do so safely, they were, essentially, authorizing stupid, venal and, as in this case, often tragic behavior.

The case was not an easy one and, frankly, made harder because the prosecution failed to present a cohesive narrative choosing instead to offer alternative and inconsistent theories. But their job was unquestionably made much more difficult by the decision of the Florida legislature to fundamentally change the behavior we will tolerate from citizens who recklessly decide to take the life of another.

There’s a lot of anger out there today. Much of it’s justified. Some of it isn’t, particularly the venom aimed at jury members. But there is one positive thing we can take from all of this: Without public outcry, George Zimmerman would never have even stood trial. That is a victory in itself.

Today George Zimmerman is not guilty. But he is most certainly not innocent. Had he stayed in his truck that night, Trayvon Martin would still be alive. Had he not appointed himself armed protector of his neighborhood, had he not ignored the police dispatcher’s admonition, had he not presumed that a black kid walking in his neighborhood was up to no good, none of this would have happened. And for that, Zimmerman, whether he feels any remorse or not, will spend the rest of his sad, pathetic life with the knowledge that he is a child killer. His life, as he once knew it, is ruined. There is, at least, some justice in that.

But not enough. Not enough for the boy in the picture atop this post (note: that picture was first shown here, on Gawker; I posted it because, if we’re going to have an honest conversation about this event, we should have an unvarnished look at its consequences), in his black hoodie and new, white sneakers, that boy who never got a chance to grow up, to be a man, to make something of himself.

I understand the verdict. But I don’t have to like it. As someone once said, “Those assholes, they always get away.”

By the way, under Florida law, Zimmerman will get his gun back.

—Follow Jeffrey Billman on Twitter, @jeffreybillman