The confession cut through the fog of burying victims and mourning in Orlando.

As locals struggled to understand how a gunman had murdered 49 of their family members, friends and neighbors at the gay nightclub Pulse, outside of the city, national media outlets reported a shocking revelation – someone could have prevented this.

At least two days after the massacre, anonymous law enforcement sources told Fox News, the Los Angeles Times, CBS News and other news gatherers that Omar Mateen and his widow, Noor Salman, had cased the Pulse site before the attack. After her husband had been killed in a shootout with police, Salman confessed to FBI agents that she drove him to purchase ammunition for the slaughter and knew of his plans to commit a mass murder at the club, they reported. On June 15, 2016, three days after the attack, the New York Post plastered Salman's face on its cover with the dramatic headline, "She could have saved them all. Killer's wife knew – but did nothing."

"ISIS-loving Omar Mateen’s wife knew he was plotting a massacre at an Orlando gay nightclub but didn’t notify authorities," the article claimed. "She was so attuned to his desire for mass bloodshed that she even tried to talk him out of the attack."

Except none of that was true.

Almost two years after the attack, evidence in Salman's trial proved many of the incriminating statements she told the FBI in her alleged confession could not have possibly happened. Two weeks ago, a federal jury in Orlando found her not guilty of aiding and abetting her husband in his support of a terrorist organization and not guilty of obstruction of justice after prosecutors accused her of lying to FBI agents during their investigation.

After ingesting fiction for so long, it was hard to swallow the verdict in Orlando. Even harder still was trying to understand why the government had charged Salman in the first place. The prosecution's case against Salman hinged on an alleged confession with enough holes to seem coerced. They never recorded her, despite FBI agents having the capability to do so. During the trial, an FBI agent let slip a damning piece of information – his superiors at the FBI knew within days after the attack that it was "highly unlikely" Mateen or Salman ever scouted Pulse before the attack, according to cellphone location data. The facts contradicted a significant part of Salman's statements – and yet, anonymous law enforcement officials leaked it to the media. Last March, federal prosecutors argued that a judge should revoke Salman's bail because her confession to casing Pulse meant she was a danger to society – a lie that helped keep the 31-year-old in a lonely jail cell for over a year, away from her son. If convicted, Salman could have faced life in prison.

Mateen, the one person most responsible for what happened on June 12, would never face a jury. But in the zealous quest to seek justice for the lives taken at Pulse, Salman stood as a perfect proxy for her husband's sins – even if she was a survivor of his violent abuse.

Noor Salman's hands shook uncontrollably.

In a few minutes, she would learn her fate from a 12-person jury who could either give her the freedom to go back to her child or sentence Salman to spend the rest of her days behind bars. Unlike the photo the media used, Salman's face was pale – no black liner rimmed her eyes and her hair stayed in a loose ponytail. Sometimes before trial started, she would send a small smile and wave to her family who sat in the rows behind her. On the day of her verdict, Salman tried to smile at her family, but couldn't – the dark circles under her eyes and petrified glance in their direction indicated she was terrified. One of her attorneys grasped her hands and held them tight.

The past month had been dedicated to delving into the most private details of her volatile marriage to Omar Mateen in front of a public audience. The first two days were dedicated to opening the wounds of Pulse. Jurors heard from tearful survivors and saw a graphic video of Mateen cruelly mowing down victim after victim in a bloody rampage. Salman – who had never set foot inside the gay nightclub – covered her face and turned away from the video as Pulse victims’ families cried. Prosecutors had called her "cold" and "callous," a person willing to keep quiet and create a cover story for her husband's suicide mission in exchange for an expensive engagement ring and designer clothes. Her defense argued she had no idea what her husband was going to do.

"If you're the wife of a man who lies to you, cheats on you, isolates you and abuses you, why would he tell you anything?" her attorney, Linda Moreno, asks. "Why would he confide in you ... He was a psychopath leading a double life who had no respect for his wife. She was not his partner, not his peer, not his confidante."

The daughter of Palestinian immigrants, Salman was raised in Rodeo, California along with her three sisters. Although she struggled with learning disabilities as a child, she did graduate high school and earned an associate’s degree in medical administration at a nearby college. Still, she worked as a babysitter, teacher’s aide and cashier. Her friends and family portrayed her as simple, kind person who loved Hello Kitty and romance novels. She wasn’t particularly religious and didn’t wear the hijab – but she did criticize terrorist acts by ISIS on Facebook.

When she was 19, Salman entered into an arranged marriage with a man from her father’s hometown in 2006. Her first husband allowed her to work at a daycare, but was also abusive, her defense said. She divorced him a few years later and went back home.

In 2011, Salman met Mateen on an online dating site. Mateen had also been married before. His first wife, Sitora Yusufiy, told reporters Mateen would hit her, take her paychecks and isolate her from family.

After a short courtship, Salman and Mateen married that same year and he whisked her to Fort Pierce – her family would see little of her after that. During her pregnancy with their son in 2012, Salman saw a radical, violent change in her husband’s behavior. She told the New York Times he punched her while she was pregnant, pulled her hair, choked her and threatened to kill her if she left. Mateen, who was heavily abusing steroids, told her she would lose her son because he would get custody, according to court records.

While in jail, Salman met with Jacquelyn Campbell, a nurse and researcher at the John Hopkins University School of Nursing who specializes in intimate partner violence. Salman told Campbell that during her five-year marriage, her husband raped her and beat her. On a danger assessment test that Salman filled out, Campbell says she scored in the “extreme danger” range – women who scored similarly within this range were killed or almost killed by an intimate partner.

"Noor Salman is a severely abused woman who was in realistic fear for her life from her abusive husband," Campbell wrote in her report. "Her behavior was entirely consistent with severely abused women who are completely controlled by a highly abusive male partner."

A psychological evaluation ordered by the court diagnosed Salman with post-traumatic stress disorder. PTSD can look different in domestic violence survivors compared to combat soldiers or first responders, Campbell explains. Most survivors don’t talk about flashbacks to one moment because abuse usually happens over a period of time, but they can be triggered into having feelings of anxiety and panic. Campbell says one woman she interviewed would feel especially anxious in her kitchen but couldn’t understand why until she realized most of the abuse she suffered happened in that room. PTSD symptoms of avoidance for abused women include trying to avoid making the abuser angry and desperately wanting the relationship to get better, in spite of evidence to the contrary, Campbell writes in her report.

"I think that explains Noor’s behavior as much as anything else," Campbell says. "In terms of how she represented herself, in terms of how frightened she was during the interrogation and in the months leading up to the shooting. She was absolutely terrified to ever ask him what he was planning, where he was going. He would just tell her to get in the car. If he said it, she did it – because otherwise he would beat her up."

About two years into their marriage, the FBI showed up at Mateen and Salman’s home.

FBI Special Agent Juvenal Martin testified that the agency had received a complaint about Mateen, who was the son of one of the agency's informants, Seddique Mateen. While working as a security guard for the private company G4S in 2013, the younger Mateen told his coworkers he was a member of Al-Qaeda and Hezbollah, and had familial ties with the organization. Martin had Mateen's supervisor at G4S record him with a hidden device, but they were not able to tape him making similar comments. FBI agents went to the couple’s apartment to interview Mateen several times with his father present in at least one of those conversations. At first, Mateen denied making the statements but eventually admitted he lied because he felt "harassed" by his co-workers for being Muslim. The agency closed the investigation.

Mateen obsessively watched extremist videos and visited websites depicting beheadings and other terrorist attacks committed by ISIS until his death. Federal prosecutors, though, failed to present evidence that showed Salman was similarly radicalized. When Salman tried to question him about the videos, he threatened her and told her to stay out of his business, according to defense attorneys. He used his phone to browse for gory videos during work and late at night – sometimes even between checking out dating websites and porn, making it hard to believe Salman would be watching with him.

His behavior took another radical turn during the summer of 2016.

For the first time in their marriage, Mateen agreed to take a trip to see her family in California, according to court records. He allowed Salman to get a driver’s license and gave her at least $500 to buy gifts and clothes for the trip – a far cry from her weekly $20 allowance. When she asked why he was spending so much money, Salman said Mateen showed her a letter from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement’s Criminal Justice Standards and Training Commission, which said he was "now eligible to enter a law enforcement basic recruit training program." Salman said her husband promised her things would be different now, according to court documents.

On June 1, Mateen added Salman and their son as payable-upon-death beneficiaries to his PNC bank account. Three days later, Mateen was at work when he watched a video where ISIL leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi called for people to carry out attacks during Ramadan.

Without telling Salman, he later went to the St. Lucie Shooting Center and purchased a semiautomatic Sig Sauer MCX rifle for $1,837; 1,000 rounds of .223 ammunition for $351; and three magazines for $40 with credit cards. It wasn’t unusual for Mateen to go to this shooting range – he had a work-issued .38 revolver, and he often bought ammunition for the gun to practice. In late May, the family went to a Walmart in Vero Beach where surveillance footage caught Mateen purchasing 200 rounds of .38 caliber ammunition while Salman and their son picked out a Paw Patrol toy in another area of the store. They paid for the items together at the checkout counter. Prosecutors said this showed Salman purchasing ammunition with her husband for the attack. But Mateen did not use his work handgun during the shooting at Pulse – it was left in the rental van he drove that night.

In the weeks before the attack, Mateen had spent more than $26,500 on credit cards buying clothes, toys, guns, ammunition and jewelry for Salman, including an $8,718 engagement ring and wedding band set.

On June 8, the couple and their son traveled to Orlando, and surveillance footage showed them shopping at Bass Pro Shops, the Florida Mall and Disney Springs. Later, they stopped at King O Falafel restaurant in Kissimmee and a nearby mosque. In her statements to the FBI, Salman allegedly told FBI Special Agent Ricardo Enriquez that after eating at the Arabic restaurant, they drove around Pulse for 20 minutes. But as the prosecution's own witness, FBI Special Agent Richard Fennern, testified it would have been "highly unlikely" that Mateen and Salman drove to scout out the club during this time. Cellphone towers near Pulse never connected with their phones.

The day before the attack seemed normal to Salman. Her husband had been treating her better and she was excited for their family trip to California – he had just bought their tickets. Mateen told her he was going out with his friend, Nemo, to dinner. When her mother-in-law Shahla Mateen called her to invite them to break fast at the mosque, Salman told her Mateen would be eating dinner at his friend's house, and that she wanted to stay home with her son.

"If ur mom calls say nimo invited you out and noor wants to stay home," Salman texted her husband. "Nemo" would later testify in court that Mateen had long used him as an excuse with Salman to cheat on her with other women. After her husband left, Salman went to dinner at Applebee's and picked up a Father's Day card and gift at Walmart. She put her son to bed and stayed up shopping for biker jackets until about 1:32 a.m. while she waited for her husband.

He would never come home.

Instead, Mateen had traveled to Orlando. Prosecutors theorized that Disney Springs – not Pulse – was the intended target of Mateen's attack, but a heavy police presence seemed to have scared him off, and he headed toward downtown Orlando. Initially, he got directions to EVE Orlando, a nightclub on Orange Avenue. But for reasons unknown, he passed the club and headed down Orange Avenue toward Pulse. After passing the gay nightclub several times while trying to get back to EVE, he finally pulled into the Pulse parking lot – a "target of opportunity," according to the defense.

He walked inside, got a drink at the bar and watched gay couples having fun on the dance floor. Minutes before the attack, Pulse security guard Neal Whittleton said in a statement that a man who later turned out to be Mateen asked him, "Where are the girls at?" Mateen watched the crowd for several minutes and went back into his van to get his guns.

At 2:02 a.m., the first shots rang out at Pulse – graphic surveillance video from inside the club showed Mateen methodically shooting at the crowd. He ignored calls from Salman and his mother but posted on Facebook, "America and Russia stop bombing the Islamic state ... You kill innocent women and children."

His last text before police confronted him was to Salman. "I love you babe," he wrote. She texted back, "Habibi what happened?!"

He was dead by 5:15 a.m., after killing 49 people and injuring 68, the majority of whom where LGBTQ Latinx and African American. Mateen didn’t only attack a gay nightclub – he shot up a home for queer and trans people, left bodies in the living room dance floor and terrorized clubgoers in their bathroom. Whether it was his intention or not that night to gun down people specifically at Pulse, Mateen attacked a safe space for LGBTQ patrons that was free of judgment, nasty stares and threats. His intentions to terrorize in response to U.S. airstrikes in Syria and Iraq are important for criminal trials and law enforcement statistics – but they matter little when almost two years after a massacre, people stay close to exit signs at gay nightclubs in Orlando.

After her last text to her husband, Salman got a call – local police officers were outside her door.

Fort Pierce Police Lt. William Hall asked Salman to come outside to talk with them after being warned of possible bombs or booby traps in the apartment. She walked out in her pajamas and he briefly searched her home. During his conversation with Salman, Hall testified in court that informed her that something had happened in Orlando, and she told him her husband was careful with guns and wouldn’t use them to hurt anyone unless he was protecting himself. Salman and her 3-year-old son were placed in the back of a police car and driven to the FBI’s Fort Pierce office, where she would remain for the next 11 hours.

The FBI agents testified they were immediately suspicious of her. FBI Agent Christopher Mayo said Salman made a strange comment during their interview when she said her husband liked everyone, including "homosexuals" before knowing the attack occurred at a gay club. During closing arguments, government prosecutors later conceded Salman could have heard police talking about the attack when she was first approached at her apartment. When they told Salman of her husband's death, Mayo said she cried while FBI Special Agent T.J. Sypniewski claimed she didn't.

For hours, they interrogated her in a large conference room – though they chose not to record or videotape her statements. Mayo said he "never thought" about taking her into one of the interview rooms at the Fort Pierce office, which had the capability to record. Sypniewski testified that it was against the agency’s policy to record people not in custody – to do so would require special permission from a supervisor. Salman technically wasn’t under arrest when she willingly talked to agents.

Agents testified that they brought Salman and her son breakfast and treated her cordially. But Mayo also said he found her sleeping on the floor of the conference room around 11 a.m. in between interviews. When Salman asked to go leave, Mayo told her she couldn’t go until they finished searching her home, so she signed a consent form to allow the FBI to search. The agents asked her to call someone to pick up her son while they continued talking to her – her brother-in-law Mustafa Abasin came to take the child and testified that he asked if Salman could go with him as well. But agents asked Salman if they could continue questioning her, so she stayed.

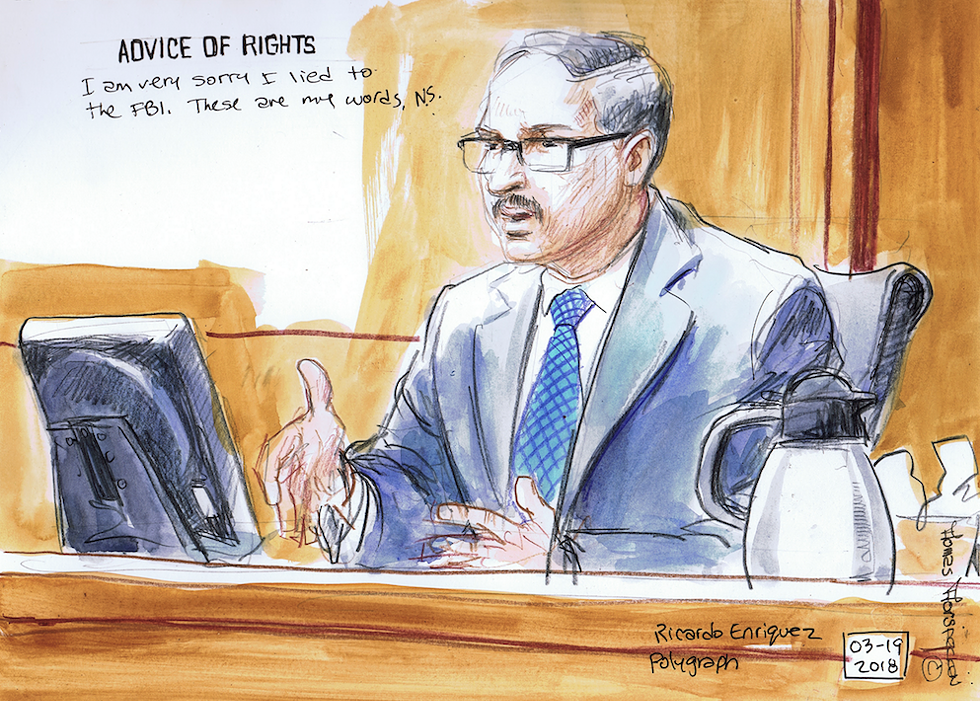

The last agent who interviewed Salman that day was FBI Special Agent Ricardo Enriquez, a polygraph expert for the agency. Enriquez testified he knew little about the shooting except for hearing an FBI official say briefly on TV that the incident at Pulse was a "terrorist attack," and therefore could not contaminate Salman’s confession. Sypniewski, though, testified that he had briefed Enriquez on what Salman had told them.

Enriquez didn’t perform a polygraph exam on Salman – instead, the agent took her into a room with no recording equipment and interviewed her for several hours. He told her if she lied during their interview, he didn’t know what would happen to her child. Salman later told a psychologist that agents threatened her son would be taken away and raised in a "Christian home."

Her alleged confessions were not written in her own hand – agent Enriquez testified during trial that he wrote her words down because she was "too nervous" and had her initial each statement. After the first statement, Salman wrote in her own hand, "I am sorry for what happened. I wish I’d go back and tell his family and the police what he was going to do."

While Salman went to the bathroom, Enriquez read her apology. He said he realized she knew more about the attack than she was letting on.

"I told her I was disappointed with her," Enriquez testified. "This statement tells me that you knew."

A confused Salman responded, "No, I didn’t."

But after Enriquez insisted that she knew and wasn’t telling him the whole truth, Salman broke down.

"She began to cry and said, 'I knew,'" Enriquez said.

In her alleged confession, Salman said Mateen had taken her to case Pulse, Disney Springs and the outdoor shopping mall CityPlace in West Palm Beach. But cellphone data location showed they never went to Pulse. Despite Salman describing a 45-minute drive casing CityPlace on June 5 around 1 a.m., defense attorneys pointed out the government provided no surveillance footage of that occurring, and cellphone location data placed the couple at Delray Beach around that time. Salman confessed to Enriquez that Mateen showed her the Pulse website and said, "This is my target," but a review of web history on Mateen's and Salman's devices and the Pulse nightclub’s server showed no evidence they accessed the Pulse website.

Salman allegedly told Enriquez the last time she saw her husband was about 5 p.m. on June 11 with a backpack of ammunition. "Omar took his handgun from the closet, put it in his holster, cover it with his shirt and said he was going to see his friend 'Nemo.'" Enriquez said that at first, Salman said Mateen told her he would see her after prayer – but after hours of being interrogated, Salman told Enriquez two more versions of the story. In the second one, Mateen told her "This is the one day." In the third version, she told Enriquez she knew when her husband left that day to see Nemo he was "going to do something bad."

But Mateen left both his holsters at home that day. His work gun, found near the rental van at Pulse, was in a blue case. Much of the ammunition he bought was still in boxes near the scene.

Dr. Bruce Frumkin, a forensic and clinical psychologist who specializes in false confessions to law enforcement, testified that Salman had an IQ of 84 and was at "higher risk" than the average person to give a false confession to investigators. Again and again throughout the hours of interrogation, agents accused Salman of lying until, it seems, she finally relented to their version of the truth.

"[She's] really extreme, particularly under pressure, in yielding to misleading information," Frumkin told the jury. "She's not the brightest. She comes across as really immature, and immaturity really doesn't help the matter when it comes to law enforcement."

After Enriquez finished interviewing Salman, she waited in a room with FBI agents for a couple hours. FBI Supervisory Agent Duel Valentine testified that Salman was worried about her son and wondered how she would tell him that his father had murdered 49 people. Mateen's actions were selfish, Salman said, according to Valentine, and she told him the laws should make it harder to purchase guns. Salman was also concerned about money – she wondered if the recent credit card debt Mateen left behind could be forgiven by the bank because he was dead. Salman, a housewife, didn’t have a job or the means to support her son.

"She was a target of them," says Fritz Scheller, Salman’s Orlando-based attorney. "Every time there’s a terrorist attack, they always investigate the wives. … From the get-go, they were focused on her, and they rushed to judgment."

After the trial, Charles Swift, one of Salman’s lawyers, said the FBI needed to view this case as a "wake-up call" for how they conduct interrogations.

"The FBI must join the rest of law enforcement and record all statements," he said. "The FBI must think about some serious reform in the wake of this … If Orlando Police had investigated this, which they could’ve, they would have done it differently."

OPD spokesperson Michelle Guido says the department’s protocols state that "at no time shall a suspect, detainee, or prisoner be in the interview/processing rooms without the [video] recorder being on."

Orlando Weekly reached out to the FBI for more information about its recording policy but did not hear back by press time.

After Salman was found not guilty, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Florida has limited its comments to saying it was "disappointed in the outcome."

"We respect the decision of the jury and appreciate their hard work and service during this trial," says spokesperson William C. Daniels.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office would not elaborate on the trial’s most controversial moments – when an FBI agent said the agency knew in the days after attack that Salman’s phone had never been to Pulse, and the prosecution’s last-minute disclosure that Mateen’s father was an FBI informant who was currently under investigation.

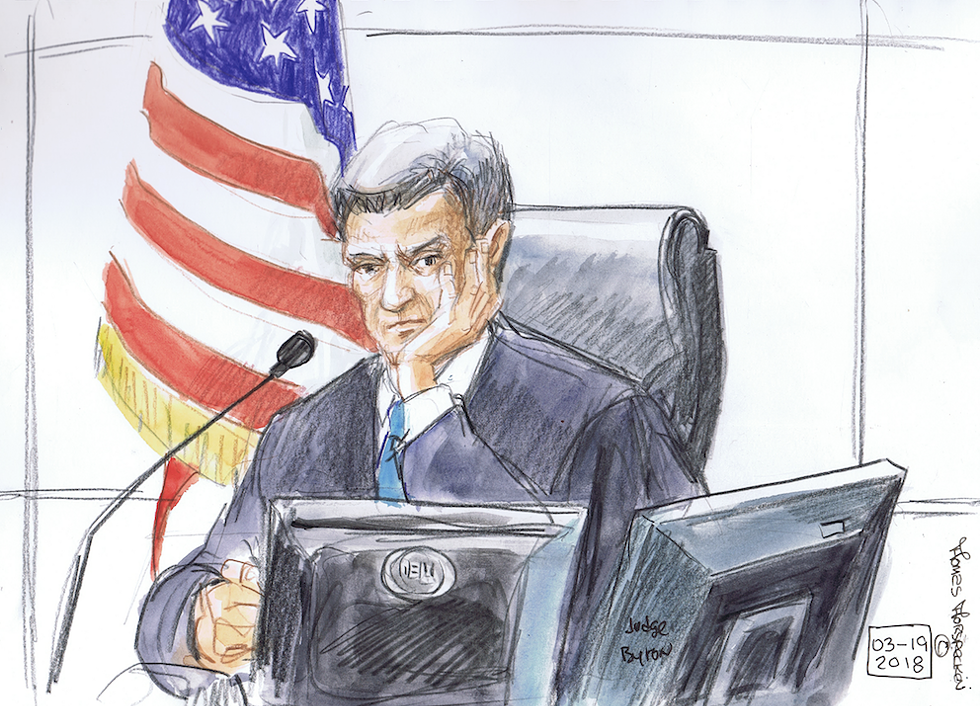

During Fennern’s testimony, U.S. District Judge Paul Byron stopped him and asked if he told anyone that data showed Salman had never been in the vicinity of Pulse. Fennern said he told his superiors, and the judge asked for their names.

After the jury left the room that day, Byron scolded prosecutors – he felt misled. In earlier filings to revoke Salman’s bail, prosecutors said she "admitted to law enforcement that she went with her husband to Orlando and drove around the Pulse night club prior to the attack." Byron granted the government's request to keep Salman in jail partially based on this assertion. Despite the government knowing this information long before Salman was even arrested, her defense attorneys received access to a presentation with cellphone data evidence last August – well after they had spent thousands of dollars in hiring experts to prove the same thing. The government is required to turn over exculpatory evidence to a defendant – failure to do so is a violation of due process.

"The government doesn't have to be told to do the right thing," Byron told prosecutors. "They must do it."

The next shock came from the prosecution’s second disclosure. Assistant U.S. Attorney Sara Sweeney revealed to defense attorneys Mateen’s father, Seddique Mateen, was a confidential FBI informant between January 2005 and June 2016. After the Pulse attack, the FBI searched the elder Mateen’s home and found receipts for money transfers to Turkey and Afghanistan between March 16 and June 5. In 2012, the agency received a tip saying Seddique Mateen was collecting $50,000 to $100,000 in donations to "contribute toward an attack against the government of Pakistan."

After discovering the receipts, the FBI opened an investigation into the elder Mateen. The defense filed for a mistrial, which Byron denied. Seddique Mateen, apparently, did not know he was under investigation and had been talking to the FBI – he was on the prosecution’s witness list. After the disclosure, Scheller informed Seddique Mateen’s lawyer Todd Foster, who he says is a good friend.

"If that had been disclosed earlier during trial, then we could have done a more meaningful investigation," Scheller says. "Noor Salman told me Seddique Mateen and Omar Mateen had a lot of contact together – but when they were around her, they only spoke in Farsi, which she doesn’t know."

Charles H. Rose, a legal expert at Stetson University puts it bluntly: "The government lied."

"Either they lied in one place or lied in the other," Rose says. "Either the FBI agent lied when they said Ms. Salman made the confession, or at some point, this falsehood about what evidence they had to prove her involvement was put out to trial, and when push came to shove, they would pull it back to what they know the provable truth to be."

Rose says the prosecution’s case was especially hurt by the FBI’s decision not to record agents interviewing Salman. After the trial was over, the jury foreman told media outlets that based on the letter of the law, they had no option but to find Salman not guilty of aiding and abetting her husband – but they wished the FBI had recorded her alleged confession.

"A verdict of not guilty did NOT mean that we thought Noor Salman was unaware of what Omar Mateen was planning to do," the anonymous foreman said. "On the contrary we were convinced she did know. She may not have known what day, or what location, but she knew."

Rose says the FBI’s procedures are organized in a way to limit taping.

"They’ve historically done that on purpose, since the time of J. Edgar Hoover," he says. "When an FBI agent was testifying on the stand, it was assumed the agent would be beyond reproach and a jury would accept their testimony at face-value. … The problem is the unrelenting assault on the action of the FBI have damaged that."

Rose says the government won’t face consequences for any potential misdeeds in the trial because Salman was acquitted. For the expert, the most impressive thing about the trial were the Orlando jurors who found Salman not guilty.

"American jurors, at the end of the day, gave her a fair opportunity for justice," Rose says. "Within a two-mile radius of Pulse, where all those people died, Floridians came together and provided justice. That’s an incredible story."

Noor Salman nearly broke her attorney’s hand as she waited for a verdict late last March.

Fritz Scheller says she was clutching his hands as the jury came out to announce their decision. When the "not guilty" verdict was read, Salman buried her face in Scheller’s shoulder as her family sobbed and hugged tightly. After the jury left the room, she hugged her tearful attorneys Charles Swift and Linda Moreno, both of whom had stood by her side in the days after the attack. None of them had been paid to defend her – Swift is the director the Constitutional Law Center for Muslims in America, which provides pro bono legal representation.

After being found not guilty, Moreno says the first thing Salman did was thank them, then ask when she could talk to her son, now 5 years old. During her time in jail, mother and child spoke on the phone every day.

"It’s disgraceful what Noor Salman went through," Moreno says. "It’s heartbreaking that she will have to spend the rest of her life along with her son to recover from this nightmare."

In front of the press, Moreno called the Orlando jury members the "last heroes of Pulse."

"Noor is so grateful," Moreno said. "[The jury] didn’t make Noor Salman the last victim (of Omar Mateen)."

In many ways, the case against Salman wasn’t different from other criminalized abuse survivors, despite the added element of alleged terrorism.

Most incarcerated women have experienced some form of domestic violence or sexual assault, says Soniya Munshi, a member of INCITE!, a national collective of radical feminists of color working to end violence against women, gender non-conforming people and trans people of color. Abuse survivors can be criminalized for a number of reasons – sometimes even for protecting themselves from a violent partner, like in the case of Marissa Alexander, a Jacksonville woman was jailed for firing a warning shot at her abusive husband.

"The criminal legal system doesn’t account for the complexity of what they’re doing to survive," Munshi says. "The charges brought against Noor show a deep misunderstanding of the experience of some domestic violence survivors."

Munshi points out the moment when prosecutors interpreted Salman’s texts to Mateen as her giving him a cover story – with context, the same texts could be interpreted as Salman communicating proactively with her husband to avoid his future abuse.

"It’s so unfair that there’s a kind of scrutiny for survivors to perform a certain way," she says. "It wouldn’t be unusual for Noor to feel love toward him at the time. Most domestic violence survivors when asked about abusive relationships, they don’t want to leave that person – they just want the abuse to stop. It can be confusing, but they’re separating the abusive person from their violent behavior because they can see the complexities of the relationship."

"Many incarcerated women happen to be survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault,” says advocate Darakshan Raja. "Seeing a Muslim women being criminalized for the actions of her partner not herself, we needed to raise awareness."

Raja helped lead the "Justice For Muslims Collective" in gathering support from 100 organizations to stand behind Salman and oppose the prosecution for scapegoating Salman in the "quest to ensure that someone pay the price for Mateen’s actions."

"Just because Noor Salman was found not guilty doesn’t mean there’s not going to be a social punishment, and it’s important for the community to help her rebuild her life," Raja says. "We also need to think about what accountability of the FBI and prosecution looks like so they don’t go around harming others people’s lives."

But unlike other cases where abuse survivors are criminalized, many of Salman’s family members expressed fear at attending her trial. Raja says the domestic War on Terror since 9/11 has led many Muslims to fear being found guilty by association because of Islamophobia. Acquittals in terrorism cases like Salman’s are rare, she adds.

"Even though her family supported her and believed in her innocence, they were afraid," she says. "If you talk to the families of people brought under these material support charges, they feel alienated and shunned from their community. If you’re seen as someone believing in her humanity, then you’re a terrorist sympathizer."

On the other side of the courtroom, family members of Pulse victims and survivors were silent as the verdict was read – many felt powerless and upset. The mother of Pulse victim Christopher “Drew” Leinonen, Christine Leinonen told the Orlando Sentinel that while Salman’s confession seemed coerced, she still believed Salman "was guilty of knowing that her husband was planning an attack and doing nothing to stop it."

Keinon Carter, a survivor who was shot twice at Pulse, says he’s still confused about what happened on June 12, but the jury looked at the evidence in Salman’s case and found her not guilty.

"She was blessed to be free to be with her child," Carter says. "It’s already gonna hurt to lose one parent. I wouldn’t wish on someone losing both parents having lost a parent myself."

Scheller says news outlets demonized his client. After the trial, Swift told reporters outside the courthouse that the media "missed the story because they depended on the government to tell it to them."

While Scheller was saddened that the jury believed Salman knew about the attack, he says he's glad they fulfilled their role as jurors and looked carefully at all the evidence to determine she was not guilty of the charges.

"I will go to my grave never believing that Noor Salman knew there was going to be an attack," he said. "I think this case was a critical metaphor for the American experience since 9/11. We’ve had a sacrifice of American values at the altar of national security. In Ms. Salman’s case, she was the other, she’s different. She’s of the Muslim religion. We make these assumptions about her, and the media certainly do that with Muslim women all the time – that they must have known what their husbands were doing. It’s this American fear of the other that still persists in our country."

Scheller says he still talks to Salman twice a day to check on her and her son.

"You know, Omar Mateen wasn’t created the night of the shooting," he says. "The evil that rested in his soul doesn’t come up in a moment before the attack. His cruelty and his inhumanity are what Noor Salman experienced throughout their marriage. She’s definitely been traumatized, but she has an essential goodness about her. … It’s going to be a long process for her and her son. Hopefully they’ll get the support they need."

Editor's note: This story is an extended version of the article we published in print on April 11, 2018.

[email protected]