Orlando's wet summer heat is a perfect time to contemplate fine art – indoors. CFAM has four excellent exhibits currently on view, ranging from stark photos by Margaret Bourke-White to luscious Dutch Masters, but My Myopia takes the viewer into a world of delicate beauty recalling the artist's native Vietnam. Trong Gia Nguyen's sculptures of old-fashioned window screens, large lattices floating in an architectural space, bring questions to mind about security and power today.

As a toddler, Nguyen and his family were resettled to Oklahoma after the fall of Saigon. Today he splits his time between studios in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) and Brooklyn. In Vietnam, he notes, the traditional "shophouse" urban lifestyle consists of one- or two-story structures densely packed along a street, with overloaded scooters, rickety bicycles, whizzing cars and wheezing trucks passing inches apart in a kind of semi-mechanized chaos. Often, windows along such a street are not glassed – there's usually no air conditioning – and instead are fitted with screens made of thin metal strips welded into geometric patterns, allowing air to flow through.

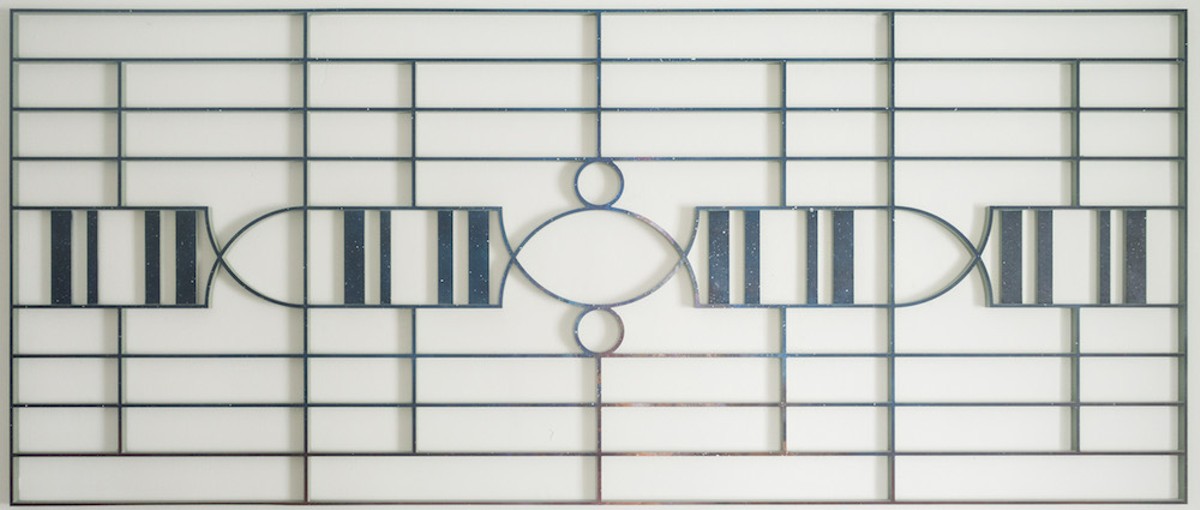

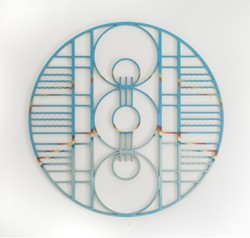

Nguyen lifts the screen out of its context and re-creates it by painting large wood panels and then carving out the screen patterns. In "Double Rainbow," the viewer sees both the geometric design and the distant sky, rainbows imprinted onto the screen's thin edges. All of the screens suspended in the gallery repeat this intriguing effect.

The push-pull of Nguyen's East-West life is condensed into this art form: CNC carving is cutting-edge, Western computer-controlled woodworking, and the screens symbolize a vanishing tradition hand-made of thin iron strips. We asked Nguyen about this during a recent artist's talk. "The screens are part of the old city," he noted. He shared a photo of these streets with a background of high-rise towers, explaining, "These are getting replaced by apartment blocks, so the shophouse lifestyle is lost."

The imagery includes the Milky Way galaxy, Thíeh Qàng Ðúc (the Vietnamese monk who self-immolated in 1963 to protest the war) and the Cambodian killing fields, but viewers can appreciate the screens' exquisite design without being familiar with the subject matter. In a subtle way, however, Nguyen holds the artist's position of power by requiring the viewer to learn in order to get the full effect.

The screens reference Vietnam's history as well as its gentrifying present. Nguyen recalls moving to Oklahoma at the end of the Vietnam War, saying that was an anxious time, yet "a time of gentler xenophobia" than today's anti-everyone-ism. With the whole notion of borders in question, the viewer can contemplate how a simple construct like a screen can unite as well as divide.