At the regularly scheduledDec. 5 meeting of the Orlando City Council, a barely audible voice brought the room to tears. It belonged to a young man, awkward with hair coloring and shyness, unexpected by the throngs of red-shirted activists in the crowd who’d come to show support for the city’s proposed domestic-partner registry – though Ryan Beck had no apparent partner, he’d come to show his support as well. Mayor Buddy Dyer had already made the mistake of suggesting that some of the assembled audience waive their right to speak in order to expedite the affair, so he listened patiently as Beck stammered through his underprepared declaration, explaining how important it would be for somebody like him to know that the city officially recognized his homosexuality as something more than an annoyance. He had been bullied, he said.

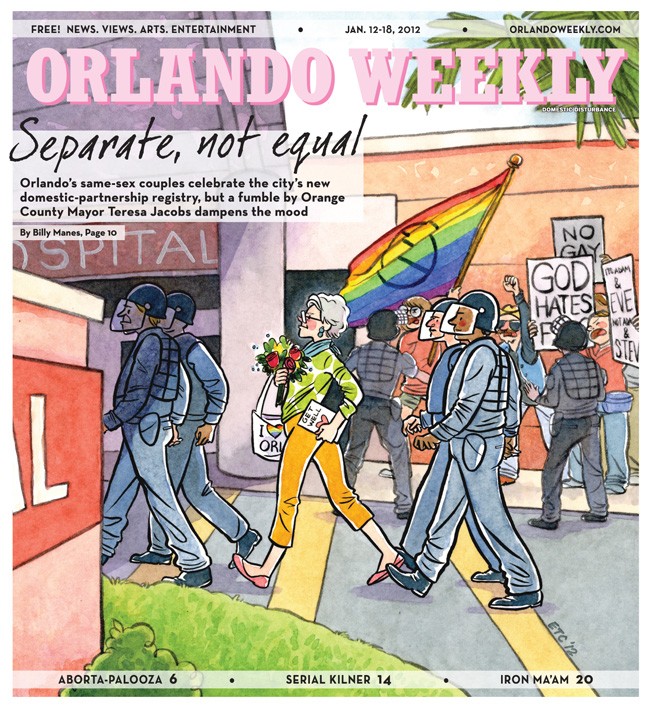

And he wasn’t alone. Activist upon activist approached the dais at City Council meetings for two consecutive weeks to argue that Orlando was on the “right side of history” in considering extending basic rights – the rights to have hospital visitation, to make end-of-life decisions, have prison visitation, share decisions about education of children within a relationship, to make funeral arrangements – to same-sex couples living within city limits. Those who spoke told their stories: couples told stories about being denied the right to visit a partner in a hospital, tales of anxiety about the potential to encounter similar situations, reflections on economic impact and explanations of deeply religious compassion (on one side) and damnation (on the other). Without much debate from the commissioners, the ordinance allowing domestic partners to register at the city clerk’s office was unanimously approved on Dec. 12. Starting Jan. 12, the city will allow its first couples to register, for $30 per couple.

From the beginning, the movement toward greater equality for the region’s LGBT community had been a two-pronged affair: first the city, then the county. Last summer, Orange County Mayor Teresa Jacobs went public with her intention to consider the matter soon after Dyer laid out his plan to pursue it. Orange County had already passed its anti-discrimination human rights ordinance in October 2010, before Jacobs’ inauguration, and Jacobs, who stumbled a little on the issue of gay rights during her mayoral campaign, seemed to be warming up to the idea, even passing domestic-partner benefits for county staff. Now that the city has passed its ordinance – including caveats to make the inclusion of the county seamless – Jacobs seems less than supportive of a countywide registry. Activists worried that her support was wavering, and she proved that their fear was justified during a press conference on Jan. 9 in which she all but dismissed the concept of a registry, voicing support instead for a more “inclusive” document that wouldn’t require an ordinance or the writing of a new law. In other words, her proposal would avoid the topic of gay relationships altogether. If the registry can’t even pass at the county level – not to mention the numerous failed state and national efforts to address marriage equality – the prospects for this last piece of the civil rights puzzle are measurably grim. You can see your partner in the hospital, within city limits: that’s equality.

Activists, however, are trying not to downplay the significance of what happened in the city of Orlando, despite what may happen in the county.

“This is an important step,” says Joe Saunders, Equality Florida’s field director. “It’s our job as leaders in the LGBT community to be moving the dial as quickly and effectively as we can.”

At the same time, activists aren’t taking Mayor Jacobs’ rejection of a registry for the county lightly.

“We are not going to be played,” says former Orange County Commissioner Linda Stewart.

Rachel Gardiner, 55, and Nicki Drumb,42, were at both of the early December City Council meetings; they waived their right to speak at the first, but at the second, Drumb – who is “terrified of public speaking” – worked up the courage to approach the dais and tell her story.

At home, curled up with a clove cigarette by a fire pit in their Colonialtown backyard, Drumb says, “We don’t have a lot of the ‘We were in the hospital and we couldn’t see each other,’ or any of that tragedy stuff.”

The pair met at the First Unitarian Church on March 3, 2003, for an anti-war reading of Lysistrata. At the time, Gardiner was ending a long-term relationship and Drumb, well, “I was a little bit married,” she says.

They reconnected the next year, and, following a gay-bashing incident outside of the Peacock Room in January 2005, took part in the Love Not Hate march organized as a response.

“Afterwards, I went to hug her goodbye, and my knees just got really weak,” Drumb recalls. A hastily assembled love note by Drumb – basically a fanned-out piece of paper with her phone number on it in case of emergency – and the two were inseparable.

“My husband and I started separating, very amicably, and we started dating right away,” Drumb says. Drumb loaded her stuff into a van and parked outside of Gardiner’s house.

“Logic says you don’t rush into a new relationship, and you don’t move in right away, but there is that lesbian thing,” Gardiner laughs. “We got an apartment, that was the spring. … That was the announcement of our second date.”

Now the couple lives together with their dog. Drumb proposed in 2006 and they had an unofficial Orlando marriage ceremony in 2007.

“It was a religious ceremony that had no legal repercussions at all,” Gardiner says. “When it started becoming legal in other places, Nicki proposed to me that we do a ‘tour’ and we go to every state where it’s legal.”

Drumb and Gardiner officially tied the knot in New York City’s Central Park last August, forgoing the financial constraints of a symbolic gypsy sojourn. They’ve also been present at the Orange County Courthouse for the past three Februaries in search of a marriage license, and they are the organizers of the Human Heart: An OUT-right Love-In event each Feb. 14 at Loch Haven Park. They feel like they are in a position to open the conversation about the rights they are and are not afforded; as graphic designers, they don’t live in fear of losing their jobs. (Gardiner, however, makes it clear that she is not to name her employer for this story; Drumb works for the Bonnier Corporation). As to whether the registry will directly affect their relationship, Gardiner is circumspect.

“It’s an eventuality,” she says. “The level of tragedy may differ, but we’re humans and we’re going to get hurt at some point; we’re going to get sick at some point.”

“What I said to somebody at the courthouse is that, ‘I’m so grateful for this ordinance, I will sign up for it on day one, but I hope I never have to use it.’ It’s tragic stuff. It’s tragic stuff.”

For Drumb, it’s more a matter of finally achieving basic rights so she can move on to other causes about which she’s concerned, like homelessness and hunger. Until then, she’ll continue to participate actively in the cause, even if begrudgingly.

“I go back and forth about playing the game and writing the speech [for City Council] and getting up there and thanking them and praising them, even though I’m terrified – and doing the Human Heart and the courthouse and all this advocacy stuff about human rights,” she says. “Then there’s this other side that just sort of lashes out and really resents it. Whose business is it out there? Why do I have to parade it all there? I’m not protesting when two 18-year-olds marry each other because they knock each other up, and the morals of that. Or someone gets married for the eighth time. I’m not there judging that or protesting that.”

On Jan. 2, Randy Stephens, executivedirector of the GLBT Community Center of Central Florida, sent out an “urgent” call to arms for a Jan. 9 town hall meeting centering on the fate of the domestic partner registry in Orange County.

“This process has dragged out for over a year and there are indications that Mayor Jacobs is wavering,” read the release.

The idea that a Republican politician in a non-partisan, municipal office would opt for a partisan, anti-gay position wasn’t new to Orlando residents with history in this town. In 2002, following her 1998 decision to allow the flying of rainbow flags downtown in accordance with gay pride, then-Mayor Glenda Hood chose to defer to the minority and vote against the historic Chapter 57 anti-discrimination ordinance upon which the current registry is built. Behind the scenes she may have been building popular consensus, but considering her ambitions for higher office – Hood soon became secretary of state under Gov. Jeb Bush – the low, socially conservative road was the safest bet. That may be the hand that Jacobs is now playing. At issue, according to gay proponents, is coverage of Orlando’s 250,000 residents versus coverage of more than one million potential participants should the county sign on.

According to a Jan. 4 Orlando Sentinel report, Jacobs had so far been dissatisfied with her fact-finding mission on the registry, yet another of her efforts not to “rubber stamp” public policy. Though she intends to meet with gay leaders on Jan. 26, some are already starting to question what her intentions are.

“Sources close to Mayor Jacobs have communicated that the domestic-partner registry is resonating with her a little differently,” Equality Florida’s Saunders said on Jan. 3. “I think our strategy is to aggressively communicate with Mayor Jacobs and the county about specific people and specific needs.”

So far, that strategy isn’t working. At a hastily assembled Jan. 9 press conference, Jacobs all but abandoned the idea that she would go through with a registry at the county level. Instead, she said that to some degree people’s fears were misguided, that the resources they would need to ensure hospital visitation already exist in law. If hospitals don’t honor those wishes, it’s up to citizens to sue. Also, Jacobs was reluctant to assign domestic-partner registries because she doesn’t think that such designations should require a shared domicile. In effect, she wants to remove gay from the equation, make it a “human rights issue.” Jacobs hopes to have the required form – or beneficiary agreement – online at the county’s website within the next few months.

“When the comptroller and I met a week or two ago … some of the concerns I had, what I was hearing about was us creating a database, me having a government employee making sure they don’t lose a record somewhere down the road, and a huge liability – not financial, but moral liability,” Jacobs says. “And when I sat down to talk to [Orange County Comptroller] Martha Haynie, I suddenly realized that this could be a much simpler issue than I could have imagined.”

That “moral liability” has become the focus of gay activists’ ire. Last summer, at the first mention of a county domestic-partnership registry, Florida Family Policy Council leader John Stemberger issued testimony in opposition that sounded very similar to what Jacobs is now promoting. When reached by email for this story, Stemberger had apparently changed his tune, saying that his group “will not oppose a domestic-partner registry which does not create a new protected class and is available to all persons.” Gay activists are now accusing Jacobs of enacting The Stemberger Plan: a beneficiary agreement without any institutional or enforceable codification of same-sex relationships.

It’s worth noting that at the Dec. 12 Orlando City Council meeting, at which the city’s domestic-partnership registry was ratified, Orange County Comptroller Haynie (a Republican) was present to vocalize “support.” She also made an appearance at the afterparty at Hamburger Mary’s and has publicly said that she would like to see the county’s registry handled through her office. Also, in the Sentinel report, Assistant County Attorney Peter Lichtman is quoted as saying federal regulations “have gaps that still leave people vulnerable,” and a registry “would solve the problem of ‘proof’ of a relationship” in legal circumstances. When Orlando Weekly first reached out to Lichtman in October, he was forthcoming in saying that the county’s approval was virtually an assumed eventuality. Lichtman, after all, worked with Broward County on its domestic-partnership registry and agreed to speak with the Weekly further on the issue locally, as well as on his success in Broward. When reached by phone on Jan. 3, Lichtman was unable to comment on anything with regard to either registry. County spokesman Steve Triggs at first downplayed the rift saying that nothing had changed and everything was still on schedule. Now, it appears, he was wrong.

As far back as Aug. 2010, Jacobs was quoted in Watermark as saying, “I have figured out that we need something that makes it official that some relationships are bona fide relationships, and that’s where I think the idea of domestic partnerships or civil unions have more standing.” This after taking heat for her supporting vote of Amendment 2, banning gay marriage in Florida. Activists now paint a picture of a retreating Jacobs’ showing her true, socially conservative stripes.

“We’ve been sitting on this for almost a year,” Stephens says. “We know the legal department is fine with it. We know the county comptroller has given her blessing to it. [Jacobs] has set up a meeting later in the month to let us know what her plans are, and that concerns us.”

As of Jan. 10, 86 couples had already scheduled appointments to register with the city, and more walk-ins are expected (21 will sign up on Jan. 12). The city has also invested a whopping $220 in capital outlay for the transition, mostly for a laminating machine and pockets in which to hold the registry cards. The fees will cover the costs. As it stands, the city is already utilizing the county’s public-records registry to document its domestic partnerships, according to city clerk Alana Brenner. $10 from each $30 registration fee will go toward paying for that luxury. Now supporters of the registry have to find a way to convince – or work around – Mayor Jacobs.

“She can say that she has expanded the realm of people that she’s willing to give a useless document if she wants to, but she’s absolutely not in any way proposing to expand any actual legal rights,” Mary Meeks, Orlando Anti-Discrimination Ordinance committee member and attorney, said in a Jan. 10 statement. “We all know people who’ve had those documents and they’ve been ignored, so please don’t give me another piece of useless paper.”

Inside a spacious 15th floor condo unit in downtown’s tony Sanctuary building, Danny Humphress, 48, and Enrique de la Torre, 44, are clearly living the sort-of-married high life. Quiet music pumps around the grand piano at the center of the living room, their two dogs are nowhere to be seen (or smelled), a giant oak bar sits off to the side of the entrance. Humphress, a self-made success in software design, homeowners association president and leader of Equality Florida’s Orlando steering committee, settles into the sofa to remember how it all began.

“We were a blind date, actually,” he laughs. “A blind date for different people.”

The two met because of a prehistoric Internet connection gone wrong; a 21-year-old de la Torre, responding to someone on CompuServe, showed up at Ft. Lauderdale’s famed Copa nightclub in March 1989, only to be stiffed by his potential paramour. Meanwhile, Humphress, on his way down from his home in Daytona Beach, picked up his car phone (“believe it or not, I had a phone in my car back then”) and heard that a friend of his had a blind date waiting for him at the Copa.

“So, 23 years later, we’re still here,” Humphress says.

It wasn’t always this easy. Humphress came out of the closet in 1985, the same year that he started his library-software business. His mother had her suspicions, but Humphress wasn’t too concerned.

“I’ve never really lived my life hiding from people. I’ve always been out there with who I am. But we never were really ones for public displays of affection,” he says.

De la Torre, born of Cuban parents, was a little more taciturn. Though the couple shacked up a month after meeting, his family didn’t find out about his sexuality until 18 years into their relationship.

“Then we went to a wedding in January, and he met my whole family, and they were all warm and welcoming and, like, who really cares? So that was a shock,” he says. “I was feeling the pressure, and they were very accepting.”

Humphress continued growing his software company (which he is not willing to name for this story, because many of his clients are churches), while de la Torre took a job at Disney. The couple relocated to the Orlando area in 1995, though they retain a home on the beach. They’ve since been officially married, on July 15, 2010, in Washington, D.C., in a private ceremony. The certificate hangs on their wall.

Following his Disney stint, de la Torre took another job before joining his partner in the software company; the COBRA insurance plan he signed them both up for translated into a genuine health insurance plan that they both currently “pay through the nose” for, according to Humphress.

That’s important, because Humphress, a small-business owner without company insurance, has a pre-existing heart-valve condition due to a bout with rheumatic fever as a child. They’ve been to the hospital before, and de la Torre worries about whether the next checkup will be “the one.”

“The term, sometimes, when they ask questions – I don’t like when they ask, ‘So, you’re a homosexual?’” he says. “Just the way the tone is, that really just annoys me sometimes. It’s not a friendly thing. What does that do? Does it put me in a different class or something?”

Since the wedding, Humphress has checked the “married” box on census forms, because “he’s my husband,” he says. They balance each other out, like Walt and Roy Disney: a dreamer and a doer, with Humphress as the former. But Humphress’ dreams of full equality are duly tempered.

“It’s never going to go far enough,” he says, referring to the registry to which they’ll be one of the earliest signees. “If that’s what we’re holding out for, then you’re never going to get anywhere. You have to make small steps. I guess the mayor could start handing out marriage licenses, but they wouldn’t mean anything.”

Not everyone is buying into the notionthat domestic-partnership registries signal a path toward equality. Late last year, Orlando mayoral candidate Mike Cantone decried the city’s registry for not going far enough. He proposed an equal benefits ordinance – one that would require companies doing business with the city to provide same-sex benefits to their employees – like the one that had just passed in Broward County. More substantially, Demian (his full legal name), the director of longtime activist group Partners Task Force for Gay & Lesbian Couples in Seattle, is of the opinion that domestic-partner registries like that approved in Orlando could actually impede eventual equality.

“Civil Union, or the numerous lesser-powered domestic-partner registrations, at first appear to be an attractive alternative. It seems more winnable – even opponents of legal, same-sex marriage have rhetorically proposed it as a ‘lesser evil,’” he writes in an essay called “Marrying Apartheid” on the group’s website, buddybuddy.com. “It nonetheless represents a system of apartheid, less heinous than South Africa’s, but similar in principle. It is plainly designed to treat one group of citizens in a separate and inferior manner despite their identical circumstances.”

It’s not an unusual rallying call. Next to the more than 1,100 federal rights and hundreds of state laws triggered by heterosexual marriage, the small sampling of dire rights offered by Orlando’s domestic-partner registry are hardly equitable.

And the federal Defense of Marriage Act of 1996 limits states or municipalities from doing much about it.

“[Domestic-partnership registries] were put into place the very first time to give some crumbs, basically,” Demian says over the phone. “They represent enormous inequity, even though we’re all U.S. citizens. … Domestic partner registrations are only valid where they are signed. Legal marriage is transferable to any state.”

Even so, more than 100 states, cities and municipalities in the U.S. provide some form of protection for same-sex couples through domestic partnerships, civil unions or marriage; in Florida, seven cities and counties have registries. As of Feb. 9, 2011, Broward County only had 25 registered couples on the books, while Miami-Dade County had 1,093.

“My perspective is that this is absolutely a step in the right direction,” says Marc Solomon, national campaign director of Freedom to Marry. “Of course it’s a positive thing when people are better able to take care of their loved ones. And it’s a way for straight people in Florida to get to know the struggles, the ups and downs, that gay people have.”

Solomon is currently in New Hampshire fighting the proposed repeal of that state’s marriage laws; he’s simultaneously hoping for a “first win at the ballot box” for gay marriage in Maine. Naturally, he’s also hoping for the best with the fight to overturn Proposition 8 banning gay marriage in California. The South, he says, still has a way to go.

“A place like Central Florida that isn’t as far along in recognizing same-sex relationships, it’s a positive,” he says of Orlando’s domestic-partner development. “It shows people that there is hope and that there is respect for their relationships.”

The battle is also, at least figuratively, being fought at the state level. State Rep. Mark Pafford, D-West Palm Beach, introduced a statewide domestic-partnership registry bill (with State Sen. Eleanor Sobel, D-Hollywood), HB 139, back in September, though, as with previous iterations of the bill, it is likely to die in committee when faced with a conservative supermajority.

“I doubt very seriously that this bill will have a hearing in front of a committee or much less a workshop. I think, frankly, the leadership, they don’t have the courage or the ability to be bold,” Pafford says. “You’ve got a system that works against people who have a different way of living; it’s a system that’s discriminatory. Frankly, Florida shouldn’t be discriminating against families or trying to define what a relationship is.”

In a sense, Floridians did that to themselves. In 2008, despite opponents of Amendment 2 – which wrote a gay marriage ban into the state constitution – spending $4.3 million (compared to $1.6 million by proponents), the initiative soared into law, 4.9 million votes to 3 million votes. Among the amendment’s proponents was John Stemberger’s Orlando-based Florida Family Action ($1.1 million donated to the cause) and Orlando Magic owner Rich DeVos’ family ($100,000). The National Organization for Marriage – perhaps the loudest group in the national gay marriage argument, and the authors of the anti-gay-marriage pledge signed by all but one of the six candidates for the Republican nomination in the Iowa caucuses – contributed just $10,000. That group doesn’t seem very threatened by Orlando’s small-time lurch toward equality.

“NOM doesn’t have an official position on domestic-partner registry. Typically, however, civil unions-type legislation is used to try to push through same-sex marriage. You’d have to be blind not to see that,” says NOM President Brian Brown from his cellphone at the Iowa caucuses. “Our focus is on marriage. Obviously we’ve got a lot of work to do on that.”

Ten years ago, Rob Domenico, 36, and Alan Meeks, 43, met outside the Thornton Park Starbucks. Inside that same Starbucks in late December, the couple occupies the far end of a leather couch while a noisy circle of Orlando police officers suck down their coffee at a nearby table.

Domenico, a community relations director for local HIV/AIDS charity Hope and Help Center of Central Florida, is an animated ball of energy (and self-professed Lady Gaga Monster), while Meeks, an expert in computer simulation, is a cautious rock.

“Obviously, being gay you have a certain amount of baggage that isn’t necessarily yours,” Meeks says. “Then, being a couple you have extra baggage. Not only do you have the normal situational issues that average people have, but you have the fact that you’re a gay couple and you have the fact that you’re gay yourself. The fact that someone in a gay couple can be together and be stable for any length of time is remarkable.”

Their relationship has endured, largely because of support from family and friends. When asked, Domenico says he hasn’t seen any situation in his relationship that would be directly affected by the city registry; though Meeks has suffered a brain tumor, Domenico says he’s already filled out the legal papers he thinks he’ll need in case of emergency. Their registry appointment on Jan. 12 will be a symbolic gesture. Unlike the other couples interviewed for this story, Meeks and Domenico haven’t made the journey to other states to codify their relationship as an official marriage.

“Marriage to me is an overloaded term. I don’t think of marriage the way some people do, in the religious construct,” Meeks says. “I think of marriage as equality in the eyes of the laws and the government that we help to support with our taxpayer dollars. I’m a taxpayer just like that guy’s a taxpayer. I’m contributing to a general fund that our government is spending as they see fit. Because of that single thing, constitutionally I should have the equivalent benefits that that guy has or that guy has, regardless of religion.”

Domenico, perhaps a little less practically, is still swept up in the romance of it all, 10 years later.

“From the day that we met, he has challenged me and helped me to go down the right path. Every step he has challenged me to grow and to really step outside of my boundaries,” he says. “He loves me like no one ever loved me. He lets me know every day. It doesn’t have to be a statement. I just know it.”

Like every other happily married couple.