Myrta Mariani is struggling.

The 40-year-old Puerto Rican native arrived in Kissimmee from the island six months ago with nothing except for her 16-year-old son and the dream of opportunity. Mariani has a master's degree in education that she can't use right now because she doesn't speak English well enough, and therefore can't find a job in her profession. Her rent is due, and the bills keep piling up.

"I was at a job interview, and the human resources person told me, 'Your master's degree is useless here if you don't know English,'" she says in Spanish. "It seemed a bit cruel to me when she said it, but it's the reality. Having my experience as a principal and as a special education teacher and not being able to work in my field is saddening."

Despite her frustrations, Mariani says she is not going back to the island. Puerto Rican Gov. Alejandro García Padilla said in June that the U.S. territory faces an estimated $72 billion in "unpayable" debt, and the economy is nearing a "death spiral."

Thousands of Puerto Ricans are fleeing to Florida as the Puerto Rican government raises the sales tax to a rate higher than any of the 50 states.

Dr. Jorge Duany, director of the Cuban Research Institute and professor of anthropology at Florida International University, says Orlando and the rest of Central Florida have displaced New York and every other destination for Puerto Rican migration. The island's financial crisis, which began about 20 years ago, has only exacerbated this movement.

According to the U.S. Census, the wave of Puerto Ricans arriving consists mainly of 18- to 44-year-olds, and a significant number are skilled workers, like nurses and teachers.

In 2012, the number of Puerto Ricans on the mainland (4.9 million) eclipsed the number still on the island (3.5 million), a Pew Research Center report said. With so many young, college-educated people leaving, it's not a pretty picture for the island, Duany says.

"Combined with an aging population and declining birth rates, the migration is depleting the island of essential human resources, which could complicate the situation even more in the long run," he says.

Despite calls from activists and Puerto Rican representatives asking the U.S. to help the people living there – and, it should be noted, Puerto Rican citizens are U.S. citizens, as the island is a U.S. territory – the White House is not considering a bailout for Puerto Rico. Leading House Republicans said last week that they were opposed to a sponsored bill allowing the territory to use the Chapter 9 bankruptcy protections permitted for states.

Mariani says that aside from high taxes, she struggled with her electricity bill, which was $400 every month, and her water bill, a steady $170 each month. In Kissimmee with $40, she can buy about a week's worth of meat. In Puerto Rico, she says, her money did not stretch very far (see sidebar for price comparisons).

"There's an exodus of people coming to Florida, and a lot of people have been asking me about moving here," she says. "The people can't endure the situation in the country anymore. We're all just looking for better opportunities and more security."

Betsy Franceschini, director of Florida's regional Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration office, is seeing the exodus, too. In one day, her office is fielding about 100 inquiries, which include calls, visits and emails, most regarding migrating to the United States, especially the Central Florida area.

"I'd say we've seen about a 15 to 20 percent increase in the number of people moving here in the past couple of months," she says.

The agency, which is a liaison between the Puerto Rican government and the U.S. government, has only one office for the entire state of Florida, located in Kissimmee. The office was reopened two years ago because growth of the Puerto Rican population in the area, currently at 900,000, is projected to hit 1 million in the coming years, Franceschini says.

"There's a huge wave that's coming over, obviously because of the financial crisis, but there's also a lot of Puerto Ricans migrating to the area from northern states like New York, Illinois, Connecticut," she says. "We're the new epicenter for the Puerto Rican population in the U.S."

Franceschini says her office provides education and orientation for people who may not be fully prepared to move here. The greatest problem for new arrivals seems to be housing and employment. Many people would like to rent while they explore local neighborhoods, but because there are not enough rental properties in the area, they are forced to buy.

The Florida PRFAA office tries to do as much as it can, Franceschini says, but with only two employees, it does not have the resources to help as much it could. The office has scheduled meetings with state departments and local governments to warn them about the services needed for the rush of people relocating here.

"Some agencies have told us 'We were not ready for all this,' and others have been more proactive about it," she says. "I think it's important to note, it's not just going to be a burden on cities, counties and states. These people are here to work, expand businesses and create jobs."

After seeing masses of people leaving the island, Florida resident William Alemán says he saw the need to give people accurate information about moving to Florida. In March 2014, he and other organizations helped organize the first Florida Expo in Puerto Rico, a conference dedicated to guiding people who are thinking of moving to the state.

The conference provides information on the public education system, retirement, housing and employment, and it even provides a psychologist to help figure out how the move could mentally impact you.

"We are not trying to encourage people to leave," Alemán says in Spanish. "But we are emphatic about the idea that if you do leave, be prepared and have all the information you can."

Alemán says that about 8,500 people came to the first conference and 20,000 came to the second conference in August. This past March, about 15,000 people from all parts of the island came to the conference.

"The majority of people who return to Puerto Rico after they move are those who don't get a job because they don't have any preparation in English," he says. "The reality is that you have to know English or you won't get a job."

Pedro Rodriguez, owner and English teacher at Escuela de Inglés Rodriguez in Kissimmee, says he sees this situation frequently with his 80 adult students, of whom about half are Puerto Rican.

After job interviews, students come into his classroom with red-rimmed eyes, bursting into tears because they were rejected once again from employment.

"Most of my students are professionals who want to work in the fields they're licensed in but feel impotent," he says. "They're looking for jobs, but terrified to do interviews because the little English they know does nothing for them."

Rodriguez noticed the uptick of Puerto Rican students enrolling in his class about six months ago. Many are frustrated because they miss the island's culture, and life is more difficult than their relatives or friends made it out to be.

"Some of them want to go back to Puerto Rico because they can't adjust, but I tell them, 'You're only going to go back to the island to suffer,'" he says. "You suffer here, but at least you can have a job and some money."

---

The cost of living

Puerto Rico’s financial crisis is partially due to the fact that life on the island is expensive. One of the main reasons Puerto Ricans migrate to the U.S. is economic. The median household income from 2010 to 2012 was $19,518, according to the U.S. Census.

The Council for Community and Economic Research announced in December that the cost of living in Puerto Rico is 13 percent higher than 300 urban and rural areas in the U.S., placing it behind such major (and notoriously high-priced) cities as New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago.

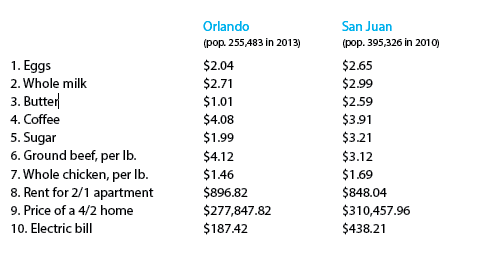

Using an online calculator from Puerto Rico’s Institute of Statistics that compares San Juan and another U.S. city using data from July to September of 2014, we compared the cost of various items in San Juan to what they cost in Orlando. According to its calculations, San Juan is much more costly than Orlando in many areas: 18 percent more for food, close to 8 percent more for home ownership, 22 percent more for transportation and 75 percent more for utilities. San Juan beat Orlando significantly only in health care costs, which were 43 percent less.

The data used is also not taking into account the recent sales tax hike of 12 percent, which is higher than any other state in the country. Here are some examples of the pricing according to the calculator: