An almost five-acre parcel in the rural area of Bithlo has become one of the most contentious issues between Orange County Commissioner Ted Edwards and the opponents trying to unseat him.

Tim McKinney, executive vice president of a nonprofit called United Global Outreach, says he plans to announce this week that he's entering the 2016 race for Edwards' spot after the two men had a public disagreement regarding the site of the recently foreclosed Lansing Street Mobile Home Park in Bithlo.

"I've never aspired to political office," McKinney says. "I see with the current political system you can only advance serious initiatives for communities ignored and overlooked for far too long if your commissioner wants to advance it. It became apparent when we hit this wall that Ted's got to go."

Bithlo, if you've only heard about it as a punch line, is an unincorporated area of east Orange County that sits on Highway 50. Since the town went bankrupt in 1929 and was later dissolved into the county by the state in 1977, the area has been neglected by local officials and the poverty level among its residents has spiraled.

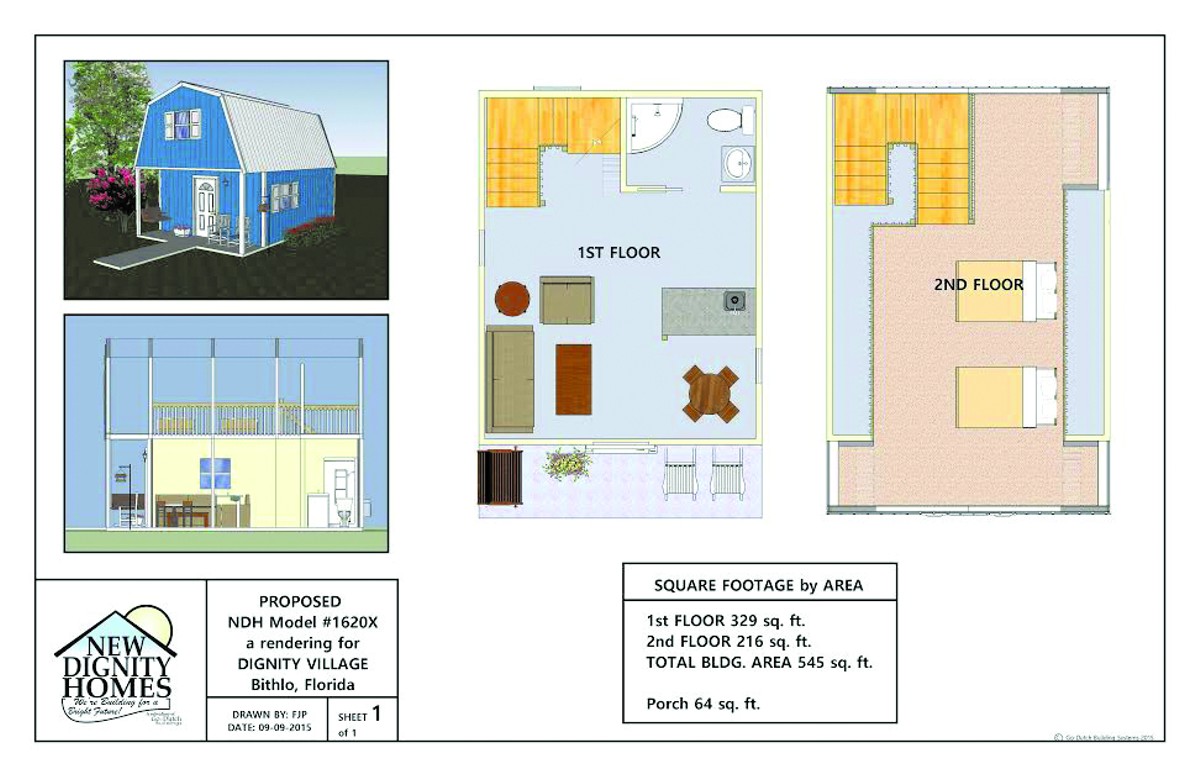

In 2009, McKinney and United Global Outreach decided to go door-to-door and ask Bithlovians what they needed most. Almost seven years later, United Global Outreach, University of Central Florida students and other colleges, Florida Hospital and other businesses – a total of 90 community partners – have transformed the community by opening a school and a medical clinic and bringing back Lynx bus service to the area. The town center, Transformation Village, is now home to a K-11 private school called Orange County Academy, medical and social services, a playground, a church and a library. Soon, the area will also have aquaponics, a coffee shop, a community garden, a small athletic field, playgrounds, a salon, a boutique, a community center and the first model of a planned tiny-housing community called Dignity Village.

McKinney says his partners wanted to install up to 43 two-story tiny homes, which would be slightly over 500 square feet and include a bathroom and a kitchen, on a foreclosed site they have been pushing the county to clean up for years. Rent for the houses would be 30 percent of a person's income, and homeless people without income would not pay rent until they could get on their feet. Edwards seemed to be on board with the project until November, when McKinney saw one of his aides post on Facebook that Edwards and Habitat for Humanity of Greater Orlando were developing a joint housing initiative to build nine to 10 regular-sized homes on the same site where McKinney hoped to build Dignity Village.

"We had a meeting days before talking about the small-home project, so it was a shocker to me," McKinney says. "After I did a public records request, I saw he had been working with them for months. ... There was no rational reason for him to treat community partners this way who are using private money."

McKinney shot back at Edwards in a column for the Orlando Sentinel in December, saying the commissioner was blocking the positive transformation of Bithlo.

"After trying for five years and exhausting every avenue I know — from gentle suggestions to aggressive prodding — I cannot get Orange County Commissioner Ted Edwards to buy into the might and momentum of the Bithlo Transformation Effort," McKinney writes. "He will not help."

Edwards responded in the Sentinel in January, slamming McKinney and Florida Hospital for not supporting the Habitat for Humanity project and because the tiny homes do not meet "environmental regulations or land-use and density regulations for a rural settlement; nor does it address an identifiable homeless problem in Bithlo."

"Notwithstanding McKinney's continuous efforts to portray Bithlo as a desperate and neglected community, Bithlo is a proud, hard-working, rural community," Edwards wrote. "Orange County has invested more in Bithlo than almost any other community in our county. ... Despite McKinney's criticism of me for not supporting his unconventional homeless village that he designed without authority for county lands, hopefully his organization will support Orange County's efforts to provide affordable housing to existing Bithlo families."

An aide for Edwards says the commissioner would not be available to comment for this story.

Habitat for Humanity of Greater Orlando's CEO and president Catherine Steck McManus says Orange County approached her predecessor years ago to talk about how the organization might build affordable housing in Bithlo. Potential homeowners have to meet three criteria: need, ability to pay and willingness to participate. Homeowners will purchase mortgages; pay utilities, maintenance expenses and taxes; attend 36 hours of homebuyer education; and with their families volunteer 300 to 500 hours of "sweat equity," which includes helping the organization build a home and working at Habitat locations. Some homeowners complete the requirements in one year, but some may take up to two, McManus says.

Before Habitat for Humanity can build anything, the county has to finish an environmental survey it is doing on the land. Trichloroethylene (TCE) is a chemical often used as a metal degreaser that has been linked to kidney cancer, liver cancer and other diseases. Beginning in 2003, the Florida Department of Health found TCE randomly in the wells of various Bithlo properties, says county spokeswoman Doreen Overstreet. County water and sewer lines do not go out to Bithlo, so residents have been using private wells. In 2012, the county sampled 240 of those drinking-water wells and got similar results as the Department of Health. Low levels of TCE were found at one parcel of the foreclosed site in 2003 and on a property nearby.

"The level of TCE that was found was deemed to be below drinking-water standards, which means the Environmental Protection Agency considers it safe to drink," Overstreet says. "If levels exceed the standard, action must be taken."

Overstreet adds that Bithlo's contamination is probably from nearby car junkyards, landfills, recycling and dumping operations, and a Circle K gas station that reported multiple discharges of petroleum in the 1980s. If TCE is found, the county can take steps to remediate it, and it could potentially declare the site a brownfield, which is a property that has the perception of contamination and could result in tax breaks for the owner, Overstreet says.

Lori Cuniff, deputy director of Community, Environmental and Development Services for the county, says she spoke with Jim Coffey, a Bithlo resident who told her his first well, built 18 feet underground, exceeded the TCE standard for drinking water. Later, he dug a deeper well that went to 65 feet and didn't hit contamination. Cuniff says the results of the environmental study should be back at the end of March.

McManus says her organization would not construct homes on the land if it were too contaminated to build.

"We have the greatest respect for the county, but they need to do due diligence to make sure property is buildable," she says. "If the tests come back showing some kind of contamination, there are some mitigation efforts that can be done."

The only other candidate currently registered to run in District 5, Gregory Eisenberg, has critiqued Edwards frequently over Bithlo's situation.

"What did 13 years of Ted Edwards get Bithlo?" Eisenberg asks in a campaign video. "No public-water access leaving residents with metal-filled drinking water and unclean bath water, a 30-year-old, 7-acre illegal dump called Mount Trashmore polluting the area, and a lack of local health care and education options."

Eisenberg says there's distrust between government officials and residents because residents don't want to be pushed out by development. Bithlovians should be allowed to live the rural lifestyle they want, but the area desperately needs water access and better infrastructure.

"There's a younger generation wondering how is this happening two miles away from where I'm getting a substantial education at UCF," he says. "There are Third World conditions down Route 50."

McKinney says that while Dignity Village is not a homeless shelter, there are homeless people living in the woods of Bithlo in tents who desperately need affordable housing, whether it's from the county or with his organization.

"I can't imagine a scenario where an 8-acre illegal dump would sit for 24 years in Winter Park or College Park," he says. "But it still sits there today, even though an Orange County mayor said it was an imminent concern to public health. ... The people here are thirsty for someone who's going to stand up and address their issues."