‘We got things out here you wouldn’t believe,” says 56-year-old Robert “Scooter” Searles as he walks with his dog Brutus along a winding path of carpet laid over dirt to keep the weeds down, deep into a plot of woods at the corner of John Young Parkway and Princeton Street.

A field of kudzu-covered shrubs bleeds into a thicket of tall trees, and the place has the atmosphere of a nature preserve; at least it does until you come upon the ramshackle homesteads of the people who call these woods home. Off the path to the right a large blue tent is quietly being taken over by the relentless kudzu.

That used to be Bicycle John’s place.

“He died,” says Searles. “Alcohol killed him.”

A little farther along the path is a clearing that contains nothing but a pile of garbage and a single, armless plastic chair. That was Mary’s camp, but she’s moved on to better digs in what looks to be a trailer. It’s hard to tell for sure, though, because Scooter doesn’t want visitors to get too close to her place.

Mary’s place isn’t the most elaborate homestead in these woods. That distinction belongs to a fenced, gated camp that sports its own mailbox and a sign that reads “Beware of zombies” out front. Within the fence are four buildings, including a three-room main house, a guesthouse on stilts, a gravity-fed shower that collects rainwater in a barrel, and an outhouse. Beer cans – Natural Light is popular – are scattered about. There’s a cooking pit, countless buckets, a generator and extension cords.

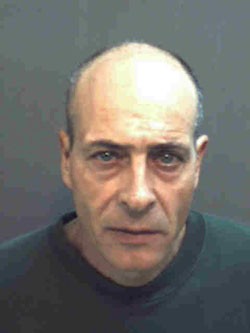

Searles says it took five years of scrounging materials and backwoods construction to create the place. He didn’t build it, though; a former resident named Nicola “Tony” Papandrea did. But Papandrea hasn’t lived in the house since Dec. 6, 2006. How he came to be an ex-resident of these woods is a story about life on the fringes of the City Beautiful, where the cops don’t even go unless they have to, and they don’t go at all at night.

On that December evening a year ago, Papandrea shot Searles twice in the torso. He walked out of the woods and confessed to the shooting, telling police that he had thrown the .22-caliber gun he used into a nearby lake. He said Searles and a friend had beaten one of his dogs, then attempted to burn down his house with gasoline and threatened to kill him. He was arrested on two counts of attempted murder with a firearm and spent the next 11 months in jail awaiting trial.

Searles, not surprisingly, tells a different story, one that involves repeated attacks by Papandrea’s dogs. It’s impossible to say if the shooting was in self-defense or an aggravated assault, because Orlando police didn’t enter the woods that night looking for evidence; in fact, they didn’t examine the crime scene at all until at least a month later. By that time, any blood or gasoline evidence that would have corroborated Papandrea’s story was long gone.

On Nov. 8, 2007, a jury found Papandrea not guilty after a two-day trial. He was released immediately and has since moved to another camp. He could not be located for this story.

The police department’s reluctance to investigate a crime involving two homeless men living in the woods either put a man trying to protect himself in jail for almost a year, or freed a shooter who is now walking the streets.

Searles has a strong opinion on which of the possible scenarios is correct. “He opened me up,” he says. “And the cocksucker got off.”

***

The camp in the woods off Princeton Street may be elaborate, but it’s not unusual. According to Orlando city commissioner Robert Stuart, in whose district the camp sits, about 60 homeless people live in the woods in the area in six separate camps.

“One of those has about 25 people, and they’ve elected a mayor,” he says. “It’s an interesting dynamic over there.”

The total number of people living in the woods throughout Central Florida is about 500 (of 7,500 total homeless), a number that rises in winter when it rains less. But most of the wooded areas are private property – the parcel at the corner of John Young Parkway and Princeton Street is held by Keybank National Association in Toledo, Ohio, and is worth $1.7 million – and the city can only respond to complaints. When complaints do come in, the city’s code enforcement department and police sweep the area. The city will contact the landowner, asking for permission to charge anyone on the property with trespassing, allowing it to remove transients’ property without their permission.

Still, the city takes a gentler approach then Orange County, says Stuart. “We don’t have the sheriff’s department policy, where you take a bulldozer out there and run over them and tell them to get the hell out.”

The camp in the woods at Princeton Street has been around in one form or another for 25 years. Some of the current residents say they’ve lived there for 15 years or more.

“And I promise you,” says Stuart, “if it’s been a history of the last 25 years, we will secure the property, it will be fine for six months and it will start over again.”

“It troubles me,” he adds. “I’m not sure what the city’s role is. If you have somebody who’s living in your backyard, and your neighbors don’t complain, have you violated the law? And the answer is that you don’t know. More to the point is that the land is not developed and that the owners are nonresident owners, and they’re not seeing these issues firsthand. Because anybody who would see them firsthand would certainly want to help to secure their property and provide quality living for the people that are there.”

Even if the owners wanted to develop the land, they might not be able to, says Stuart, because much of the wooded area is wetlands.

Meanwhile, the city organizes biannual philanthropic missions, sending food providers out – with protection – to try to help the transients find a way out of the woods. But the fact that the camp is on private property limits how much the city can do.

“Any of those wooded areas are private property, so we won’t really go on people’s private property,” says Orlando police spokesperson Sgt. Barbara Jones. “Sometimes what can happen is somebody will come out of one of those areas that’s very populated with trees, they’ll come out and make a phone call and say, ‘Hey, I got robbed,’ and we’ll come back in with them when they can give us some kind of direction of where we’re going.”

That’s what happened in August when police were investigating a missing person, 49-year-old Stephen King, in the same area. They were guided to the area by a witness, and found King’s body. He had been shot with a .380-caliber handgun and left facedown in a lake under some shopping carts. Police arrested Robert “Red Dog” Davis, 47, and charged him with first-degree murder.

***

On the evening of Dec. 6, 2006, Nicola Papandrea returned to his camp after being at a nightclub. What happened next depends on who is telling the story.

According to a statement Papandrea gave to Orlando police, Searles and his friend Raymond “Buzz” Mackenzie were drunk that night and loitering inside the fence of his camp. Mackenzie had a machete, Papandrea told police, while Searles was waving a baseball bat. The two were threatening Papandrea’s barking dogs. There is a history of antagonism among the three, with Papandrea even calling the police in the past when, he says, Mackenzie pulled a knife on him.

Papandrea said Searles struck his dog Max in the head with the bat and the animal fell to the ground whimpering. Papandrea picked up the dog, carried it back into his home and retrieved his .22-caliber handgun. He ordered Searles and Mackenzie out of his camp, threatening to shoot them if they didn’t leave. They responded by saying that they were going to kill his “motherfucking ass,” and poured gasoline around the camp to burn it down. Papandrea said that when the men approached him, he shot at them four or five times in self-defense and they ran away.

Next, according to Papandrea’s statement, he walked to a friend’s camp across John Young Parkway and said that he wanted to turn himself in. Along the way, “mad and disgusted,” he tossed his gun into a lake on the west side of John Young Parkway. His friend walked Papandrea to John Young Parkway, where they flagged down a police car. He confessed to the crime. Police found eight .22-caliber bullets in Papandrea’s pocket, but they never found the gun.

According to Searles’ version of events, Papandrea’s dogs often escaped from his fenced camp and had attacked him. He says he carried a stick – an ax handle, not a baseball bat – to protect himself from the dogs, and says other camp residents carried weapons to protect themselves too.

In a sworn deposition, Searles says he and Mackenzie had been drinking beer at his place after Searles’ day of work at Florida Ceiling Systems when they heard the dogs barking. When he went to check on the noise, Searles says one of the dogs attacked him. He swung his stick in self-defense, fighting off the dog until Papandrea arrived.

“Tony, I ain’t got no problem with you,” he recalled saying. “It’s your dogs. You’ve got to keep the dogs squared away. Somebody’s going to get hurt out here.”

But Papandrea responded with the following threat, says Searles: “You’ll never see the damn holidays.”

Mackenzie, who had come up behind Searles, headed back to his place to check on it, and Searles went back to his own camp across the path from Papandrea’s. A few minutes later, Papandrea stood just outside of Searles’ camp, pulled out his gun and fired from about 10 or 12 steps away. He hit Searles twice: once in the stomach and once below the armpit. Searles, still standing, yelled to Mackenzie for help and then made his way out to Princeton Street to get help. Orlando Fire Department responded and transported Searles to ORMC.

Doctors cut off his clothes -– much to Searles’ chagrin, as he was wearing a new pair of pants – treated his bullet wounds and put 38 staples in his stomach. He was released Dec. 13 and stayed with a friend through January.

Searles says police told him they couldn’t go into the camp the night of the shooting to look for evidence, and they didn’t visit the crime scene until late January, when he returned to the woods. The only record of the police going out to investigate the shooting is from Feb. 20, when crime scene technician Stephen Williams took photos at the site more than two months after the shooting.

***

When the case came to trial on Nov. 7, the state attorney’s office was so confident they could put Papandrea in prison that they were looking into having the minimum sentence increased from 20 years to 25 years. They had a statement from camp resident Darlene Downson, who heard the shots and alleged that Papandrea hit her dogs a lot. They had a statement from Mackenzie, who vouched for Searles’ assertion that Papandrea had threatened him.

But the case fell apart when the eyewitnesses couldn’t be found to testify. Coupled with the fact that police had no physical evidence to indicate what happened, the case turned into a circumstantial argument about which man the jury would believe: Searles, who had previous arrests for a DUI and drug charges, or Papandrea, who had no criminal record.

The prosecutor’s notes from the trial portray the state’s frustration: “OPD did nothing,” attorney Will Jay wrote. “Honestly shouldn’t have been filed.” “Self-defense was the obvious defense, and with no shell-casings or blood or pictures of those things, it was a smearing match.” “Victim convicted felon.”

Christine Warren, Papandrea’s court-appointed lawyer, stops just short of saying cops didn’t care about the case.

“I wouldn’t want to say that the police just didn’t care because they were homeless,” says Warren. “But there wasn’t the dead body; there was a guy who was shot twice and ended up with two bullets in his body, and it may have been partly because they don’t care. I think it was just as much, however, that there wasn’t a clear line of responsibility in terms of who was supposed to do what and who was supposed to follow through.”

Warren suspects that the only reason photos were taken at all was pressure from the state attorney’s office. By not going out the next day, she says, cops missed the chance to find crucial evidence like machete marks, blood from the dog or even from Searles that would pinpoint the location of the shooting, and residue from gasoline poured around Papandrea’s camp.

Police also missed the chance to recover another crucial piece of evidence when they couldn’t locate Papandrea’s gun, she says. “He said he threw it in some lake, and I think they may have gone out there with the idea of maybe looking for it. He showed them the place, the lake, that he threw it in. But I think they decided it was too marshy and they wouldn’t be able to find anything in there. They couldn’t send the scuba divers in to find it.”

So the case came down to a soft-spoken Italian immigrant with a fifth-grade education versus a boisterous victim prone to drinking and trouble with the law.

Juror Erin Jessel, 27, believed the former, as did the rest of the jury.

“We totally sided with Tony just because when he got up there it was so obvious that this guy couldn’t hurt a fly, that he was fighting for his life that night,” she says. “And the fact that they didn’t have any evidence – yes, he might have slapped someone four times – but, you know, `Searles` has a cocaine record and a DUI record, and Tony has nothing.”

Jessel says police testimony “didn’t jive,” because of discrepancies like one cop putting the shooting at 8 p.m. and the other 10 p.m. “The police give them no respect,” she says. “They could have gone the next day. That’s why we pay for police and investigators. The investigator that was at the hearing seemed like a really nice and intelligent person, and he even said that he was the one that realized that nobody had done anything about it. He went with `Searles` to the hospital and then he came back and thought that it had been taken care of by another investigator. And nothing was done, and he was like, ‘Didn’t someone go out there and take pictures?’ So they finally went out there and took some pictures … of nothing.”

***

In the woods at Princeton Street and John Young Parkway, Searles – who is admittedly drunk on a December afternoon a week after the anniversary of being shot – is quick to lift his shirt to display the scars from that night. He can joke about it, but just as often he’s angry about the turn of events. Occasionally he wells up in tears. The day is still clear in his mind, right down to details like covering his face as Papandrea fired the gun.

“I’m already ugly,” he laughs. “I don’t need to get any uglier.”

He recalls the doctor who treated him saying his girth saved his life that night. “He said, ‘If you weren’t so goddamned fat, you’d be dead.’ Thank God for being a fat boy, 265 pounds and I’m proud of it.”

For the most part, though, he feels cheated.

“I was in Vietnam, I was shot at and didn’t get hit,” he says. “I was in Germany, I was shot at and didn’t get hit. I was an escort to the president in Washington, D.C., I was shot at and didn’t get hit. I move to Florida, I get two bullets in me.”

[email protected]