Colonial Drive Facts | Jungle Adventures | Colombia Bakery | Orlando Fashion Square | Church of Scientology of Orlando | The Jungle MMA and Fitness | Magic Mall Flea Market | Barnett Park | Strictly Skillz

The oil splotches and exhaust bifurcating the strip-mall sprawl that’s come to define the east-west equatorial divide of Orlando’s most well-traveled commercial artery, Colonial Drive, don’t elicit much in the way of nostalgia. Gridlocked into near-anonymity, our stretch of State Road 50 is as much a nuisance as it is a necessity – a car accident waiting to happen in the middle of a road-rage nightmare – and many of the businesses littering the landscape speak to big-box impulse shopping or a fast-food escape, not the quaintness of the neighborhoods nestled away on either side of it. It is probably the first (and worst) thing you’ll notice about Orlando upon arrival. And this will become the road you’re most likely to avoid.

But it wasn’t always that way. It was once known as State Road 22, but in 1924, it was rechristened Cheney Highway, named after Orlando-based U.S. Attorney John Moses Cheney. A bottle of Orange County’s finest orange juice was reportedly shattered on the road to mark the occasion. The celebration of the brick-paved infrastructural wonder carried over onto theater screens nationwide via Fox Films newsreels. Florida, at the time, was at the height of the rural cobblestone phenomenon, ranking third in the nation with 389 bumpy, bricked thoroughfares. We were going places. “The Cheney Highway traverses virgin wilderness, winding [through] beautiful woodlands, along sparkling water courses and silvery lakes, making a drive of continuous interest from Central Florida to the sea,” gushed a 1925 issue of Florida Trucker magazine.

By the postwar era, Cheney Highway was due for expansion. On Nov. 27, 1947, the Thanksgiving Day Sentinel-Star (later the Orlando Sentinel) beamed out the headline “Ocean-to-Gulf Highway Will Pierce Central Florida” with all due fanfare. The Cross State Highway – or State Road 50 – would connect the existing East Orlando portion of Cheney Highway to a $9 million public works omnibus plan that would (with some winding and aberration) stretch to both coasts and open up commerce for Florida’s citrus farmers.

Though the ensuing years have seen State Road 50 (or, in Orlando, Colonial Drive) thrive and falter like the rural economy it virtually replaced, there’s still a certain character, history and charm to its flat-surfaced dullness. To find it, we visited a variety of businesses and landmarks lining the historical path to see if the street could still tell a story. It can: It’s the story of Orlando.

Colonial Drive Facts

State Route 50 runs throughout Central Florida, from Weeki Wachee on the west coast, to Titusville on the east. The highway is called by different names in different regions, such as Cortez Boulevard in Hernando County and Colonial Drive in much of Orange County. Parts of the highway east of 436 (Semoran Boulevard) follow the old Cheney Highway, the original road that ran from Orlando to Titusville.

When driving along Route 50 from Orlando to the east coast, you may see a large, decorated Christmas tree on your left-hand side. That tree marks the location of the town of Christmas’ Old Post Office Museum. The museum is home to a collection of ornaments from the White House trees of five presidents, a year-round nativity display, historic post office memorabilia and a collection of 150 bride dolls in native dress.

“Originally, the roads going into Orlando were just trails, and they did not follow the path of Highway 50, or what we call Colonial Drive today. What they ended up doing, in the probably late nineteen-teens and 20s, was make a road called Cheney Dixon Highway that went from Florida City, now known as Titusville, where it dead ends at the Indian River, all the way to Tampa, just like 50 does. The path is very much the same. It’s a bit off in different areas – it was very much more windy then than it is now, but it follows a very similar direction.” – Vickie Prewitt, recreation specialist, Fort Christmas Historical Park

Excerpt from From the Florida sand to the City Beautiful: A Historical Record of Orlando, Florida, by E.H. Gore, published in 1951: “Mr. Charles D. Sweet, a surveyor from Louisiana, located in Orlando in 1873. He had traveled up and down the Mississippi Valley and got a desire to see what Florida looked like. When he arrived in Orlando, he liked it so well he decided to locate. He surveyed part of the city when it was incorporated in 1875 and laid out some of the streets. He wanted to make Gertrude Street a main thoroughfare through Orlando but when the South Florida Railroad was built in 1880, it followed through a large portion of that street. That street was named for his sister Gertrude. He was elected to the board of Aldermen in 1880 and served as mayor in 1881. He wanted to name the streets running east and west after different mayors so started out with Marks and Sweet streets, but some time later the name of Sweet Street was changed to Colonial Drive. He was one of the pioneers who helped change Orlando from a village to a city.”

1926: F.B. Mills opens a new residential subdivision on 60 acres of land along Colonial Drive, between Hampton and Bumby, and names it Colonial Gardens after the successful gladiola-bulb business and plant nursery he ran on the property before developing it.

1927: City creates a police informational booth at the corner of West Colonial Drive and Orange Street to offer information to tourists traveling through the area.

1953: 24 parcels of land along Colonial Drive are taken in the county’s largest condemnation suit to date.

1954: Completion of the Colonial Drive section of the East-West Highway spurs rezoning of the city from Orange Blossom Trail to Mills Avenue. Much of what was once residentially zoned is opened to commercial development, and Colonial Drive is officially dedicated as State Route 50. “Official dedication of Colonial Drive was held Aug. 18, with the Acting Governor Johns the honor guest,” says Eve Bacon’s Orlando: a Centennial History of the affair. “A parade and street dance highlighted the celebration, with Cracker Jim (Hanley Pogue) in charge of a hog-calling contest.”

1955: Western Way Shopping Center on West Colonial Drive opens, with Moses Pharmacy and Landis Stone’s Hardware Store as anchor tenants.

1956: Colonial Plaza shopping center opens.

1960: Evangelist Oral Roberts draws 10,000 faithful to Orlando for a 10-day religious revival set up in a huge tent on West Colonial Drive.

1963: Highway 50 is widened into four lanes and the first traffic light at the corner of East Colonial and Maguire Boulevard is installed.

1974: Speed World, a 3/8 mile high-banked oval racing track, opens near the intersection of State Routes 50 and 520, 15 miles east of Orlando.

1974: Town gossip Charlie Wadsworth’s Orlando Sentinel column Hush Puppies details a controversy involving the renaming of Cheney Highway to William B. McGee Highway by Gov. Reubin Askew. McGee was a 29-year employee of the Florida Department of Transportation. Sen. Bill Gibson, R-Orlando – pressured by the Orange County Commission – brokers a deal with the Florida Department of Transportation to split the highway: McGee on the west, Cheney on the east.

1975: First Vietnamese refugees arrive in Orlando, according to Orlando: a Centennial History, Vol. II. According to the book, a Saigon neurosurgeon and educator, Dr. Pham Huu Phuoc and Nguyen Ninh Hoan, were sponsored for emigration by Orlando psychiatrist Dr. E. Michael Gutman. Gutman and his wife formed what became known as “the Gutman Shuttle,” which helped more than 1,300 families relocate from Vietnam to the United States after the fall of Saigon. The Gutman Shuttle is credited for the dense population of Vietnamese immigrants that settled in Orlando throughout the ’70s. Gutman died in 2009.

1999: Orange County Commissioner Homer Hartage proposes redevelopment of West Colonial Drive. Hartage’s attempt is followed by a 2002 Special Design Overlay District for West Colonial Drive from North Pine Hills Road to Good Homes Road. Numerous businesses are unhappy about the restrictions designed to reduce blight.

2009: Of the twelve most dangerous intersections in Orlando (which was named the most dangerous city for pedestrians by Transportation for America) traveled by performance artist Brian Feldman, five of them cross Colonial Drive: North Pine Hills Road, North Hiawassee Road, North Goldenrod Road, North Alafaya Trail, North Semoran Boulevard.

Jungle Adventures

26205 E. Colonial Drive, Christmas

Erin Sullivan

If you’ve ever driven the length of Colonial Drive, aka State Route 50 once you’re outside Orlando city limits, from Orlando to Titusville, you’ve seen Swampy, “the world’s largest gator.” He’s a 200-foot-long concrete behemoth that stands guard over an iconic bit of Floridiana that’s more than just the campy tourist attraction it appears to be from the outside.

Enter the gift shop and ticket counter through the mouth of the giant gator, and you’re instantly struck by the smell – that’s not a reptilian aroma that’s penetrating the air, it’s sulfur. The moat that surrounds this wildlife preserve is fed by a sulfur spring that keeps the water at a pretty constant 70-something degrees, perfect for the year-round cultivation of our state’s most infamous toothy beast.

Back in the 1960s, when Highway 50 was just a two-lane road and there wasn’t much in the way of development (much less sprawl) east of Orlando, gator farming was a booming trade in this area. Entrepreneur Hermon Brooks got in on the business in the late 1960s and selected this site for Brooks Alligator Farm, which raised gators for meat and hides. His curious endeavor quickly drew attention from people traveling back and forth to the coast from Central Florida. “He put out a sign that said ‘Brooks Alligator Farm,’ and people would stop and want to see these gators,” says Ramona Lashbrook, operations director at Jungle Adventures. “So he started leaving a coffee can out for people who stopped, so they could leave donations.”

Over time, the tourism aspect of the business began to take on a life of its own: In the early 1970s, Brooks opened Gator Jungle, a wildlife park that put commercially farmed gators as well as other wild animals on display for the public.

Though the gators still come from the Brooks’ farm (Herman Brooks’ two sons, Shane and Wayne, aka “Hoho,” run Brooks Brothers Alligator Farm next door to Jungle Adventures to this day), the business of Jungle Adventures these days is based on preservation, rescue and education, not breeding, farming and selling.

More than 200 gators, ranging from hatchlings less than two foot long, to a 30-year-old, 15-foot monster named Goliath, live in a swampy, duckweed-filled moat and in displays around the preserve. They share this space with a host of other beasts, both mundane and exotic: white-tailed deer, peacocks, coatamundis, Florida panthers. Many of the animals that call Jungle Adventures home are rescues turned over by Florida Fish and Wildlife authorities after being confiscated from neglectful owners or illegal situations. Take, for instance, Prada the Rhesus monkey, who was brought to the preserve after being confiscated in a cruelty case when it was discovered that he had been brutally beaten by his owner, or the pair of ring-tailed lemurs that landed at the park when their owners could no longer keep them. Other animals here on display were purchased at auction. When mom-and-pop zoos and attractions close, Jungle Adventures wildlife educator “Safari Todd” explains, the animals go up for sale to the highest bidder. Those not purchased for educational or conservation efforts often meet a cruel fate.

“Have you ever heard of a canned hunt?” he asks a small audience during a recent Sunday afternoon hands-on wildlife show, in which viewers learn about (and handle) gators, tarantulas and invasive species like pythons. In states where the activity is legal, he explains, tame animals are set loose in pens and shot by trophy hunters – it’s a practice Todd makes it a point to disparage during his talks with the public.

Jungle Adventures has partnered with Hands on Wildlife Safari, a nonprofit eco-education organization, that allows the park to offer lectures and demos, wildlife safety programs and handling classes to the public.

“By the time you leave here, you’ve come into contact with something you’ve probably never experienced before in your life,” Todd says. That includes being just a few short feet and a scrawny chain-link fence away from a 12-foot alligator during feeding time.

“Head up, Bonecrusher!” Todd calls out to one of a half-dozen huge gators sunning themselves alongside the park’s moat. The animal raises his massive head and opens his jaws wide so Todd can toss a hunk of meat into his gaping maw. The audience is so close you can practically feel the rush of air when it snaps its mouth shut. You certainly would never get that close at Disney, Todd likes to remind park visitors. Indeed.

None of this is readily apparent from the highway, of course – from its façade Jungle Adventures looks like just another roadside attraction, a fading relic from a bygone era when State Road 50 really was the only way to get from one side of the state to the other. “We hear that all the time,” Lashbrook says. “‘We never knew it was there, we thought it was just a gift shop.’”

Colombia Bakery

10438 E. Colonial Drive

Aimee Vitek

We make the pastries fresh every morning,” affirms Diana Castrillon in a thick Spanish accent. She uses a damp cloth to wipe down the two-top where a mid-morning customer recently enjoyed coffee and a buñuelo (Colombian donut). The cozy seating area inside Colombia Bakery, which holds fewer than 20 people, is teeming with the aroma of freshly baked dough and brewing coffee. A large, glass display case sits at the center of the room, chock full of both sweet and savory traditional Colombian fare: arepas (corn cakes), empanadas (fried corn meal pockets filled with meat), papa rellena (stuffed potato balls) and pandebono (bagel-shaped bread with queso fresco and guava). An adjacent case holds packaged food products – fried plantain chips, fruit candies – shipped in from Colombia and delivered by a distributor in Miami. This time of the morning, just before 9 a.m., Castrillon greets patrons who are looking to grab a quick cup of Colombian java, a breakfast pastry and La Prensa newspaper before starting the workday.

The owner of Colombia Bakery, Jorge Mora, opened the place about five years ago, says Castrillon, and though originally from the Republic of Colombia, Mora has been a Central Florida resident for almost 40 years. While Mora doesn’t typically frequent the bakery, save for the occasional check-in, the interior decor pays homage to his home country with a large photo on canvas of a rural Colombian farm house that hangs on the room’s prominent wall; on another wall, hangs a framed black-and-white photo collage titled “Bogotá ayer” (which translates to “Bogotá yesterday). The sizeable sign out front sits along Highway 50 in east Orange County, bearing the outline of the Republic of Colombia, with colors indicative of its national flag – yellow, blue and red (which has faded to pink).

Castrillon is one of three employees who work full-time at Colombia Bakery. During her seven years living in Central Florida, she’s worked at the bakery for the last three. When asked if she makes the pastries, she laughs, shakes her head and points to the store manager, a middle-aged Hispanic man by the name of Luis. Translating for Luis, Castrillon explains that he arrives around 6 a.m. each morning to prepare the food for the day. Castrillon is the only employee at Colombia Bakery who speaks English.

Colombia Bakery is location on Highway 50 in the Union Park area of east Orlando between Dean and Rouse roads. Situated just far enough west of the college-crazed University of Central Florida corner of Alafaya Trail and about six miles east of the buzzing intersection of Semoran Boulevard, it’s a quieter strip of Orange County’s active Colonial Drive drag. As with Colombia Bakery, surrounding businesses indicate that there’s a thriving Hispanic- and Latin-influenced community in this area: the Alamo Plaza across the street is home to Maria Bonita Mexican & Cuban Restaurant, and the Salsa Heat Dance Studio and La Casa de las Paellas restaurant are located a block or two away in either direction. “Most of our customers are Hispanic,” Castrillon says, “some Colombian and also a lot of Puerto Ricans.”

During the past 10 years, a number of neighborhoods in east and southeast Orange County, including Union Park, where Colombia Bakery is located, have seen immense growth in the number of Hispanic residents and business owners. As confirmed by one U.S. Census Bureau report obtained by the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce of Metro Orlando, Orange County’s Hispanic population rose 83.09 percent from 2000 to 2010. And according to the report, in 2010, Hispanics made up 26.9 percent of the population of Orange County. For Hispanic residents in Central Florida, small cafés and businesses like Colombia Bakery offer a taste of home with familiar menu items, as well as sundries such as international calling cards and money-shipping services for those with family still living in Latin America.

The steady mid-morning breakfast flow subsides at Colombia Bakery. “It gets busy around 3 or 4 p.m.,” Castrillon explains. Typically, that’s when a late-lunch crowd fills the bakery, often ordering the most popular menu item, the daily lunch special for $5.99: choice of steak or chicken, rice and beans, and plantains. Also, written in Spanish and taped to the window, a piece of paper with the words “employee is needed for the kitchen.” Castrillon tidies up another table near the window and then steps behind the counter to put on another pot of coffee.

Orlando Fashion Square

3201 E. Colonial Drive

Billy Manes

Outside the Colonial Drive entrance to Orlando Fashion Square, two elderly women with walking canes squint into the sunlight as they stand beneath squares depicting lifestyles of fashion – happy couples in warm embrace, gleeful children, vaguely ethnic portraits of success – that hang two-dimensional and still over their heads. That widening gap between the shopping mall’s business model and its reality only continues through the point-of-sale thoroughfare indoors: an empty tattoo parlor, an empty nail salon, an empty massage storefront giving way to the only business that seems to be attracting any customer fluidity, Panera Bread.

Gone are the days of the pinkish bubblegum smack and the putrid wafts of Crabtree and Evelyn runoff overexciting the teenage masses into cliquish semi-inhabitance. The rite of passage that led to such mass-market retail realities as Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Mallrats has distilled into a schizophrenic sense of lowbrow utility. Also, it’s hard to champion consumerism in the middle of an economic depression, even at Hot Topic.

But that’s a half- (or almost completely) empty perception, says Orlando Fashion Square’s marketing director, Dave Ackerman. Following a lengthy, and unexpectedly engaging cultural history of what malls have meant to people, Ackerman concludes that the original purpose of indoor shopping outlets – as a town center that is as much about culture as it is convenience – is on its way back.

“We don’t necessarily shop anymore as a recreational activity; we’re not so consumed with status and brands,” he says. “We start realizing that as we sprawl and build, we again want to revisit repurposing what we already have, spaces that already exist.”

The roots of Orlando Fashion Square date back to October 1963 when a freestanding (and still standing) Sears outlet was built. The rest of the mall was the brainchild of Pompano Beach developer Leonard Farber, a patron saint in the mall trade, who developed the 70.5-acre property in 1973. In the ensuing years, anchor stores like Burdines (now Macy’s) and Robinson’s (later Maison Blanche) were enough to attract a multiplex theater and the development of a food court, making it an all-purpose attraction fit for losing a full day.

But there would be challenges. In addition to the development of Florida Mall in 1986 and the more upscale Mall at Millenia in 2002 – both buffeted by transient tourist traffic, Ackerman says with palpable disdain – shifts in personal tastes that led to outdoor shopping centers and outlet malls have dampened Fashion Square’s fashionable glimmer. So Ackerman, who came to his post at the end of 2007, has worked to redefine what fashion is. Most notably, the mall became home to the National Entrepreneur Center (formerly the Disney Entrepreneur Center) in April, something that Ackerman says could help sustain the mall itself. People who want to test their entrepreneurial impulses through the center’s resources could “transfer some of their efforts into real-world opportunities” at a kiosk or a store in the mall. There are, as is indicated by the numerous Orlando-themed postcard walls where stores used to be, many vacancies.

“I definitely think we’re very encouraged,” Ackerman says. “After a year and a half of more closures than openings, there’s been a readjustment.”

Part of that readjustment has been more interactive sales via mobile kiosks; retailers are trying harder. “In 2005, you basically opened your door and rang into a register,” he says. “In 2011, there’s a little bit of a return to the experience of shopping.”

But you wouldn’t know it from looking at Fashion Square on a weekday afternoon. The food court is virtually empty, several kiosk attendants are reading their iPads to pass the time, one man is ironing out a hair extension as he tries to peddle a straightening iron to a woman whose hair is already straight, there are vibrating massage recliners being unused. It is a plastic ghost town.

“Sometimes I think that people look at our malls and they don’t realize that the hallways are immense. It tickles me,” Ackerman offers by way of explanation, or overstatement. “When you’ve got a football field in between, of course it’s going to look empty.”

Church of Scientology of Orlando

1830 E. Colonial Drive

Paul Hiebing

You’ve likely walked by the Church of Scientology’s storefront a thousand times and hardly even noticed it. It’s impressively bland (especially when compared to its Rubik’s Cube neighbor Sam Flax), and there’s little to entice you to come inside, save a few half-hearted placards advertising “free stress tests” set up on the sidewalk outside.

Inside, the space is just as drab: posters hung on plain drywall, worn carpet leading down boring hallways. Strings of party lights hung from the drop ceiling for a church function do little to dress the space up.

Since 1982, this has been the nondescript home of Orlando’s Church of Scientology, the infamous religion based on the writings of sci-fi author L. Ron Hubbard and embraced by celebs like Tom Cruise and John Travolta. Given the ribbing the religion has taken in the media (including extended assaults on Comedy Central’s South Park) and the negative attention it has received from those who’d just as soon call it a cult as a religion (Scientology has, for instance, been the target of an extended campaign by hacker group Anonymous, which seeks to dismantle it and see its status as a religious, tax-exempt organization revoked), you’d think the church would be a bit more scrutinizing about those it lets walk through its front doors. However, as at most churches, walks-ins are welcome and visitors are greeted with a smile and a firm handshake. The storefront church is open every day of the week, and Sunday services are open to participants of any faith.

When you walk in the door you’ll quickly be asked “Do you want to know more?” by someone on duty, and if you answer in the affirmative, you’ll be whisked into the media room, a destination decorated in sharp and fashionable contrast to the rest of the space: flowing burgundy curtains, a podium and a flat-screen TV adorn the room where the damage control begins.

“What have you heard?” you may be asked. An innocent question but loaded, considering the controversies and negative attention Scientology has received in the media. You can answer what you want: stuff about Hollywood celebrities, the Dianetics commercials from the 1980s, Tom Cruise. They’ll tell you about local volunteer ministers who have assisted in local homeless shelters or at disaster-recovery sites around the world.

Then they’ll show you some DVDs. A disc is inserted into the TV, the lights go dark and you’re alone in the room when a Hollywood-crafted documentary about Scientology’s founder, L. Ron “Flash” Hubbard, begins. He’s an impressive guy. Twenty-one Boy Scout merit badges, Eagle Scout by age 13, worldly jetsetter, WWII soldier, amateur psychologist, self-help guru to the stars and, finally, founder of Scientology. Fin.

The next video begins. Young, attractive people tell you why they are Scientologists (“I love helping people!” is a common theme) and soon the greeter returns to ask you what you think so far. He asks if you know that matters of the spirit can be scientifically measured (you didn’t) and tells you that they can (though you don’t believe it) if you use the right equipment, like the Scientologists’ patented E-meter.

More videos play, working an angle opposite the one most religions use: moral imperative. Scientology focuses instead on the idea that the preservation of one’s self – survival – is the ultimate goal in life and that Scientology has got the strategy for survival down to, well, a science. Your greeter may ask if you’ve ever felt exhausted after work, if you’ve ever finished reading a page of a book and forgotten everything you just read, if you ever felt like you just didn’t understand something. There are strategies to get around this, he says – strategies that Scientologist technology can fix. The selling point propping up the philosophy is the insinuation that the end result of Scientology’s improvement of your life is the accumulation of wealth.

If you walked in a skeptic, you’re likely just as skeptical – if not more so – after walking out. But you’ve become better acquainted with one of the oddities that can be found tucked among the noodle shops, Asian health food stores and boba tea counters that are ubiquitous along this stretch of Colonial Drive. It’s a curious spiritual mile marker that, in its own way, fits in well with this eclectic stretch of businesses, all of which are somewhat mysterious until you walk in the front door.

The Jungle MMA and Fitness

1419 E. Colonial Drive

Justin Strout

This year has been a big one for Mills 50, the approximately 30-block district that takes its name from the intersection of Mills Avenue and Colonial Drive (aka State Road 50). A marketing push to brand the area with “Mills 50” banners has brought new attention to the traditionally quirky, LGBT-friendly area that includes Colonialtown, Lake Eola Heights, Park Lake Highland, Hillcrest and a punchy, second-floor office that houses a certain local alt-weekly newspaper. Business is booming.

The Mills 50 restaurants, of course, have garnered the biggest media buzz, and rightly so. From the flowery Dandelion Communitea Café to the famous Bananas Diner, not to mention the widest selection of Asian cuisine in town, as well as scene staples like Will’s Pub, Wally’s and the Cameo Theatre, there’s no shortage of people-watching pleasure. On any given day, one might see fixed-gear enthusiasts, food-truck prowlers and pub-crawlers galore.

Perhaps only in the Mills 50 area, though, can someone spot, in the same visual horizon, nurses shopping for scrubs, down-on-their-luck DUI class attendees and a capture-the-flag battle royale in a rain-filled ditch behind an auto-parts shop involving sweaty, mud-covered wrestlers. The nonprofit Mills 50 Main Street Co. touts this area as “the intersection of creativity and culture,” but it’s not clear exactly how this kind of spectacle fits in.

Strangely, it’s not as unusual as one might think for the Mills 50 district: The aforementioned wrestlers, often spotted lugging monster-truck tires around a sparsely used parking lot, are part of a brutal conditioning class at the Jungle MMA and Fitness, which is part of a proliferation of martial arts studios in the area – including Gracie Barra Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, which teaches the style of the world famous Gracie family. So why the concentration of kicks and punches? It’s a natural fit, first of all. The martial arts originated in Asia, and the Mills 50 Main Street Co. calls its Asian community “the cultural cornerstone of our district” on their website. But Patrick Hennessey, general manager of the Jungle, points to a more practical reason: This is where the gear is.

“We have a great relationship with East Coast,” Hennessey says of East Coast Martial Art Supply, the Colonialtown South storefront that has catered to karate needs in the area since 1979 – and happens to neighbor yet another dojo, Martial Arts World. “They’ve been here forever.”

Hennessey also believes the popularity of the sport itself, which has seen ups and downs as fads have come and gone, from The Karate Kid to the Ultimate Fighting Championships, has had an impact. Five or six years ago, Hennessey says, interest in MMA might have been more “spread out.” These days, businesses specializing in the sport can be found nearly anywhere, but Hennessy says the Jungle, which has been open for about four years, “is not just some fly-by-night place trying to capitalize on the trend of MMA.”

Hennessey says auto traffic in the area is “horrible,” but he says the “foot traffic” in the Mills 50 neighborhood has contributed to his gym’s success. Many of his customers are locals who’ve driven or walked by and spotted a class training outside.

“We have people that come from Clermont and Apopka, but mainly it’s people downtown that might have seen one of our shirts at L.A. Fitness and ask about it,” he says. “Word of mouth around here is great, and the crazy tire-dragging stuff outside gets some attention. People drive by and slow down, like, ‘What the shit are they doing?’”

Magic Mall Flea Market

2155 W. Colonial Drive

Jessica Bryce Young

At 7 p.m. Saturday night, Nov. 19, Colonial Drive west of Orange Blossom Trail is a river of cars, five lanes wide and dammed by orange barrels and yellow police tape. (Woe to the driver who wants to pull a U-turn; the tape-and-barrel construct extends for blocks.) For those who are not simply caught in traffic, the destination point is the spacious parking lot of the Magic Mall at 2155 W. Colonial Drive. It’s Florida Classic weekend, and a significant segment of the folks in town for the annual Citrus Bowl showdown between Florida A&M University and Bethune-Cookman University are here to show off their cars or ogle others’. The shiny, shaved, jacked-up American cars on 30-inch rims called donks are the main flavor, though plenty of intimidatingly tall trucks are present as well. The cars are directed (with more tape and barrels) into a slow processional around the lot, stereos bumping, surrounded by lesser cars like pilot fish, drifting in a grand circle until pulling into an isolated parking spot, the better to be admired from all angles.

Inside the roughly 100,000-square-foot flea-market-cum-mall, business is good, but not great. Clumps of young women drift around the periphery in an unconscious echo of the cars outside, frowning critically at costume jewelry and hair extensions; a couple banters while negotiating who’s buying what for whom at one of the many stalls trading in gold jewelry priced by the pound (or fraction thereof).

The Magic Mall specializes in goods for the so-called “urban” shopper: framed art depicting African-American families, hair products, oversized rims, local hip-hop mix tapes, hugely baggy T-shirts and shorts, Jamaican horror/comedy videos, and smile-brightening gold-and-diamond grills. In fact, it was the presence of a stall plastered with pictures of children wearing grills that prompted MediaTakeOut.com to post a shot from the mall in April, with the title “In Our CONSTANT SEARCH For The RATCHETEST City In America ... We Think We Found A Winner …. ORLANDO!!! … you can go the Flea Market. And there’s a place where they sell GRILLS … just for kids!!!! Orlando …. c’mon y’all … what is wrong with you …” Comments from readers were split between disapproval (“*HANDS IN FACE* LAWD HAVE MERCY!!!!”) and fondly defensive nostalgia (“MAGIC MALL BABY … U CAN GET YA HAIRDONE, TATTOOS, FOOD, SHOES, CLOTHES, GRILLS, CDS AND T SHIRTS FOR THE DEAD HOMIES … I STILL LOVE MY CITY ...”).

Before the Magic Mall became Orlando’s go-to spot to buy XXXXL T-shirts, it was a Kmart, says Porfirio Sanchez, proprietor of Magic Arts and Variety, a stall selling pinup prints and designer smell-alike perfumes. In the early 1990s, the empty building was leased by a group of Korean businesspeople and transformed into a flea market. When the Korean group decamped farther west to open the Magic Mall Outlet at 5176 W. Colonial Drive, they took with them many of the original vendors and patrons. Business began to decline, but it’s hard to say whether that was the change in management or the general decline in the economy. “We’re surviving, but I don’t know how long I’m going to stay here if I don’t see more money coming in,” Sanchez says. (He’s been there 16 years, but his business used to occupy many more square feet than it does now – as did the market itself, he says.) “It was nice … I made a lot of money. As soon as Bush took over [sales] went down,” Sanchez says, with an ominous whistle.

Aside from its economic woes, the Magic Mall saw trouble in February, when, in the culmination of an investigation launched in 2009, the FBI arrested four men on federal drug charges. The 28-year-old proprietor of Vitamino Discount and Gift Items and Magic Metro, Ali Abdul-Amir Joumaa, was accused of selling substances used to cut cocaine and heroin.

Interestingly, the Orange County Property Appraiser’s website lists the Magic Mall’s owner as the Chesley G. Magruder Foundation. In 2006 (the most recent tax documents available), the foundation made grants totaling $611,250 to Orlando Shakespeare Festival, Orlando Philharmonic, Orlando Museum of Art, and Lake Highland and Trinity preparatory schools, among dozens of other arts, charitable and Christian organizations. Their rental income from the Magic Mall that year was $274,414. Although the bulk of the foundation’s net worth is in financial investments, it’s notable to realize that the sale of hair products and T-shirts is supporting the efforts of some of Orlando’s loftiest institutions.

For what it’s worth, I didn’t spot the “Grills for Kids” stall on any of my recent trips to the mall.

Barnett Park

4801 W. Colonial Drive

Paul Hiebing

Cloistered between the Scylla of the Orlando Auto Auction and the Charybdis that is the Central Florida Fairgrounds in Pine Hills sits one of Orlando’s most underappreciated city treasures. Perhaps you’ve heard of it – it’s called Barnett Park.

It’s easy to be misled about what you’ll find when you get there. The tiny dirt entry into the park’s complex, after all, is flanked by a dingy parking lot on one side and a dusty flea market on the other. But once you worm your way down the drive (and over several nerve-rattling dips in the road) you find yourself baffled that the Orange County Parks and Recreation department doesn’t have a bigger boner about this park.

Spread out over 159 acres of well-kept grounds, Barnett Park is home to a ton of activities. There’s a paintball arena, a pro BMX track, two 18-hole disc golf courses, batting cages, golf driving ranges, tennis courts, a skate park, a boat launch and that’s only scratching the surface. The disc-golf courses are peppered with challenging hazards, making effective use of the natural ponds, dense and spiny brush, and (admittedly not-so-natural) power poles that give the park much of its character. It’s hard not to appreciate living in Orlando while casually walking around the outdoors on a warm winter afternoon, haphazardly chucking discs into the unknown, listening as the breeze catches the “pip-pip-pip” of paintball duels in the distance.

Barnett Park also houses a fitness center and gymnasium, the latter of which has a regulation-sized basketball court used by area schools. Sitting like a stucco bulldog in the middle of the park, the fitness center contains your typical arrangement of workout equipment, but offers its amenities to the neighborhood (and general public) for just $100 a year. And some truly interesting community activities happen in there, as well – tournament games of the Orange County Clash, Orlando’s own quad-wheelchair rugby team, for instance.

If you want to really appreciate the impact of the place, though, you’ve got to go there on the weekend. You can’t come on a weekend and fail to miss the smell of barbecue or hear the squeals of children playing at a party. (Side note: Whoever is renting the bounce houses, weekend in and weekend out, to groups using this park has got to be making killer bank.)

And it’s found in the unlikeliest of areas in Orlando: off West Colonial Drive, where car lots and strip malls rule the landscape like paved golems.

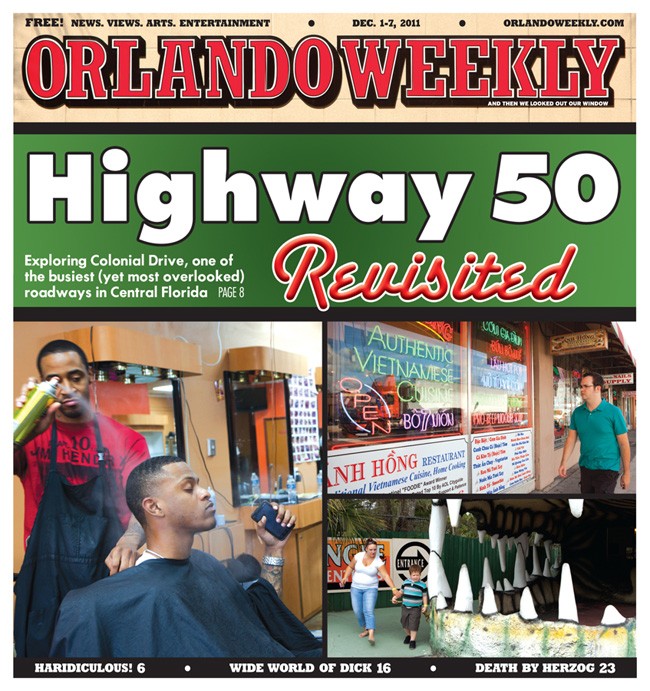

Strictly Skillz

400 County Road 431 (near the corner of West Colonial Drive)

Jeff Gore

On a recent November evening, in one of the few glowing storefronts in an otherwise dim strip mall on Pine Hills Road, Reggie Trammell, Jermario Anderson and Brian Berry are buzzing, clipping and trimming. Four other males, including an adolescent, are waiting for the same treatment; the barbershop, called Strictly Skillz, closes at 9 p.m. on most weekdays. The owner is Berry, a 38-year-old native of Columbus, Ohio, who bought the shop formerly known as Sport Cuttz in February of 2007.

Berry, his two barbers, the seven customers in the shop and the amorphous handful of men chatting outside all have something in common: they’re black. Berry’s barbershop is barely a minute’s drive from State Road 50, which forms the southern boundary of Pine Hills, an area with a population that is 68 percent black (Orange County, taken as a whole, is 21 percent black). Because Strictly Skillz falls just south of West Colonial Drive, it’s technically considered part of Orlovista, but that’s a majority-black area as well. In African-American communities, Berry says, “The barber shop is a social spot. We get people to hang out, congregate with their friends.” Perhaps not coincidentally, there is not a single Great Clips, Hair Cuttery or Supercuts in Pine Hills, though with a population over 60,000, the area is large enough to be considered its own designated place separate from Orlando, according to the U.S. Census,

Despite the apparent bustle inside Strictly Skillz on this evening, however, Berry guesses that he’s lost about 50 percent of his clientele during the last fifteen months. This is not due to the creeping decay of a recession, but according to Berry, a very distinct “black eye” inflicted on August 21, 2010.

It was the last Saturday before the beginning of the school year, and, according to Trammell, “It was nothing but kids in here. [The] boy I was cutting was about 10 years old.” Suddenly, five Orange County deputies – including a narcotics agent – entered Strictly Skillz, ordered the customers out of the store, and cuffed Berry, Trammell and Anderson without any questions asked. This “sweep operation” would soon move next door to Jazzyt Hair Designs and Accessories, where owner Jackay Patterson was detained and arrested while a state investigator broke into a locked room with a pry bar, though a subsequent state investigation of the raid found that he had no authority to do so. “They just came in tearing through everything,” Patterson says.

Judging by the military nature of the pre-planned operation – all in all, nine barbershops in and around Pine Hills were visited in a similar fashion that day – it’s perplexing that its stated goal, formulated in conjunction with the state’s Department of Business and Professional Regulation, was merely to “enforce statutes and regulations concerning barbers and cosmetologists operating without being properly licensed.” Strangely, the cops didn’t bother to ask Berry, Trammell or Nelson for their licenses before putting them in handcuffs, which is how they remained for nearly a half hour – until their licenses were retrieved and verified as current. Nobody at Strictly Skillz recalls an apology. Even more bizarre is the fact that a DBPR inspector had visited Strictly Skillz two days earlier; she could have easily found that the shop and its barbers were operating legally. But instead, she was busy gathering “intelligence information such as number of exits, number of people inside the establishment and number of stations,” according to an administrative review by the DBPR.

Three state employees were fired in the raid’s aftermath, but that’s not nearly enough to appease Berry, who calls the event “racial profiling, plain and simple.” Indeed, judging by the state’s and county’s own reports, the hunt for those committing the crime of “barbering without a license” was most likely an excuse to invade minority-owned barbershops with the hope of seizing guns and drugs (which, in a few cases, is exactly what happened). It’s for that reason Berry announced on Oct. 24 he would be suing both the county and the state for monetary damages, though he won’t disclose a dollar amount. “We want to make a stance for the black communities, for the African-American barbershops, for all the barbershops across America,” he says.