Before June 12, you could ask people in the city where they were from and they would usually respond with the name of another state, says Mayor Buddy Dyer. But since the mass shooting at Pulse, he hears people say, "I'm from Orlando." The City Beautiful promised not to be defined by those terrifying hours of hate, and it has kept to that by responding with compassion, from the heroism of first responders to the long lines of residents at blood banks. Orlando was a beautiful place to live before Pulse, but on the city's darkest day, it embodied love when choosing to blame someone would have been easier. And that, as Robert Frost would say, has made all the difference.

Allysia Williams aka Sierrah Foxx, performer

In the year following the Pulse massacre, thousands of people have come to pay their respects and leave tributes at the club. But Allysia Williams, who lives blocks away from the site, can't go past Pulse because of the memories. That night, as she stood at the edge of her driveway, she saw cop cars flying down Kaley Street toward Pulse and two terrified boys running toward her, shouting that someone was shooting inside the club. Williams, who performs as a drag queen under the name Sierrah Foxx, couldn't believe someone would gun down people at the place where she often performed. Williams let the two boys inside her home to take refuge. They were texting another friend still inside the club who was pretending to be dead. When the friend stopped texting, the two boys started to cry and Williams told them all they could do was pray. They prayed in her living room until 5 a.m., when the blast from police at Pulse shook the picture frames off her walls. Williams says it breaks her heart to think that her brothers and sisters who were dancing at the club that night were just trying to celebrate being gay and free. "I'm 45 and I've been through my ups and downs," she says. "I remember saying to God, 'Why couldn't it have been someone like me instead of these people that were so young and so innocent? Why did they have to go?'"

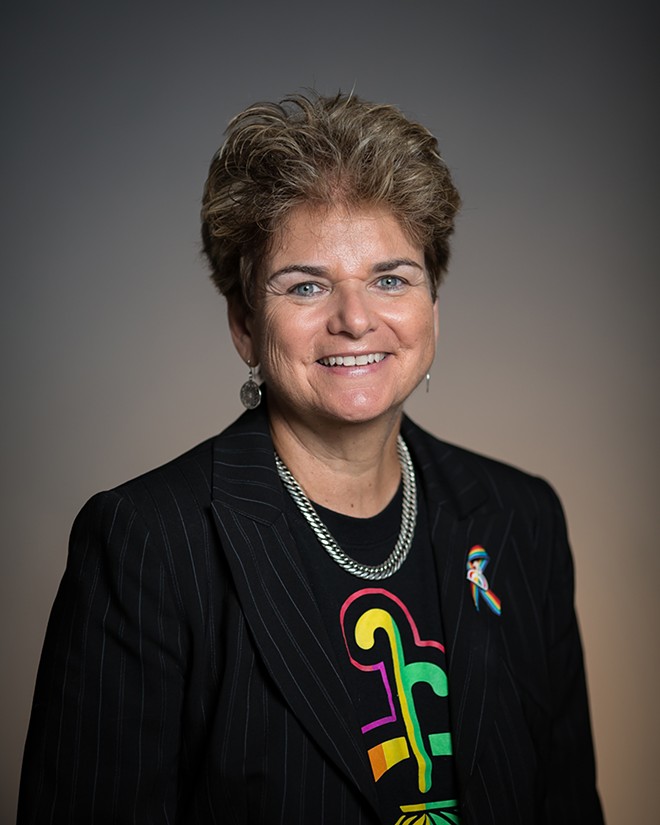

Patty Sheehan, Orlando City Commissioner

Orlando's first openly gay City Commissioner, Patty Sheehan, says Orlando showed the world on June 12 how to stand up to hatred with community support and love. That morning, she remembers being on the street with Terry DeCarlo, director of the GLBT Community Center of Central Florida, as the world found out how many lives had been taken at Pulse. As she and DeCarlo held each other and cried, a local minister offered to pray with them. Photographer Joe Burbank captured the moment. "I will never forget that feeling, at that moment, and being so grateful to be surrounded by friends like Terry who have done service work in the LGBTQ community for so many years," she says.

Dr. Michael Cheatham, Orlando Regional Medical Center

As patient after patient rolled into the Orlando Regional Medical Center during the early morning of June 12, Dr. Michael Cheatham and his team remained focused on the victims despite the devastation around them and even during false reports of another shooter at the hospital. After working for hours to save people, Cheatham remembers one of the hardest moments that day was when he and another doctor had to read a list of survivors to hundreds of desperate family members clamoring for any information about their loved ones. The cries of anguish still stick in his mind. The next morning, Cheatham and hospital staff went right back to work to continue taking care of Pulse survivors and other trauma patients. "They left whatever they were doing and got out of bed at 3 a.m. to come to the hospital to work even though they weren't on duty," he says. "It's what we do as a trauma center because of the commitment we have to the community."

Katie Wright and Mallory O'Neill, Papa John's Pizza on Mills Avenue

Katie Wright was on vacation when she woke up Sunday to the news that a mass shooting had happened in her hometown. Wright, director of operations for the Orlando region of Papa John's Pizza, called the Papa John's on Mills Avenue and asked employees to help in the only way they knew how – by taking pizzas down to the GLBT Community Center of Central Florida. Mallory O'Neill remembers an "eerie feeling" in the air as she drove the pizzas down to the hundreds of people gathered at the Center who were crying and hugging each other. She and other workers delivered more than 200 donated pizzas around Orlando that day, even taking orders from customers in New York and Boston. "It wasn't just a delivery for me," she says. "It was our team helping in the way we could."

Dr. Joshua Stephany, Orange County Chief Medical Examiner

Bodies don't bother medical examiner Dr. Joshua Stephany. But going in to identify the victims of the Pulse shooting, he felt like time had stopped at the crime scene. "Picture any nightclub in the country at that hour," he says. "People buying drinks, buying food, they're paying bills, people are dancing and joking, and the music is still pulsating. And then take away the people. It was surreal." Many were touched when Stephany and his office decided to keep the bodies of the victims and their killer in separate rooms, out of respect for their families. It was a small, comforting gesture from the office, but it inspired people to send the office thank-you letters and even food. "When you're the medical examiner's office, you can't do much after the fact – the only thing we can do is reunite victims with families as soon a possible," he says. "It does sound like a cliché, but in the darkest hour, we really can see greatness in people."

Barbara Poma, owner of Pulse Nightclub

For Barbara Poma, Pulse was a way to celebrate the legacy of her brother John, who died of complications from HIV/AIDS in 1991. Terrible and profound events happened on June 12, but what still stands out in Poma's mind is the sense of community felt in the city after the worst mass shooting in modern American history. She plans to turn the club site into a national memorial and museum that honors the victims, their families and survivors. "I think it's fair to say that the rest of the world has been able to see Orlando as it always has been – accepting, strong and loving," she says.

Rich Martin, director of K9 deployments at Lutheran Church Charities

The golden retrievers (like Ruthie, above) that flew to Orlando after Pulse had already been to the site of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting and the Boston bombing, says Rich Martin, director of the comfort dog program at Lutheran Church Charities in Illinois. They visited hospitals, vigils, media stations, dispatch centers and dozens of other locations around the City Beautiful for two weeks to provide a calming moment for hundreds who grieved in the days after the massacre. "Many times they will lead us to the person that most needs it," he says. "They know who needs love."

Elizabeth Moreno, manager of the OneBlood donor center on Michigan Street

When Elizabeth Moreno got into work at the OneBlood donor center on Michigan Street at 9 a.m. the morning of June 12, the building was already at full capacity. People distraught over the massacre at Pulse stood for hours in long lines under the summer sun to help in one of the only ways they knew how. At one point, more than 600 people were waiting at the center to donate blood. Moreno and her team finally stopped working at 4 a.m. the next morning after the last donor left. By then, they'd been collecting blood for 21 hours. "The compassion and outpouring of love and support for the community helped keep us going," she says.

Joshua Granada and Carlos Tavarez, firefighter paramedics with Orlando Fire Department

Joshua Granada and Carlos Tavarez were dropping off a patient with stomach pain at ORMC around 2 a.m. when they heard gunshots in the distance. Far away from their home station in Parramore, they drove their ambulance down the street toward the police lights and sirens clustered around Pulse. Granada and Tavarez stopped close to Station 5 on Orange Avenue and saw firefighters dragging a man into the station. The two men immediately grabbed the man and sped off toward ORMC with their first patient. Trip after trip, the firefighter paramedics used their small ambulance to transport one-third of the 44 patients for the half-mile ride to the hospital throughout that morning. "I just remember telling one guy, 'You're not going to die today,'" Granada says. "Technically you're not supposed to say that, but that's what that person needed to hear." Tavarez credits the muscle memory they developed during training for the amount of victims they were able to help. "It took me a few days to fully realize what that was and what part we had in it," Tavarez says. "Some days you're angry, and sometimes you're OK. We were just trying to the do the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people."

Michael Perkins, executive director of the Orange County Regional History Center

A woman's rosary beads from the Vatican. A couch from IKEA covered in writing. A small treasure chest filled with 49 sparkly pink and red hearts. These are just a few of the tribute items that Michael Perkins and his staff at the Orange County Regional History collected and preserved from memorials around the city after the Pulse massacre. For weeks, his staff was out in the hot sun, cleaning candle wax and other debris from the things mourners left behind. "It's hard enough for us as adults to understand how somebody could do this, impossible for a child," Perkins says. "But the simple, handwritten messages of hope, love, peace and support left by children just really spoke to me."

Mayor Buddy Dyer and Heather Fagan, City of Orlando

Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer remembers his deputy chief of staff Heather Fagan's face was a stark white when she came to tell him the actual number of people that had died at Pulse. In those confusing first hours after the shooting at Pulse had ended, it would have been easy for residents to respond with fear and anger, not only toward the shooter but also the Muslim community. "We were going to have to support each other and this community was going to have to come together," Fagan says. Together, Dyer and Fagan crafted a message that they hoped would inspire Orlandoans during the darkest moment to choose love and compassion over hate. "Were we going to be known as the site of the worst mass shooting in history?" Dyer says. "Right out of the box, we said we wanted to be defined as something different than that." The final message was an iconic line from Orlando's longest-serving mayor: "We will not be defined by the act of a cowardly hater. We will be defined by how we respond and how we treat each other."

Chef Kevin Fonzo, owner of K Restaurant

Chef Kevin Fonzo found out about the massacre at Pulse just after closing for the night at K Restaurant, his award-winning College Park eatery. After the initial shock, Fonzo recognized a familiar face among the victims – Cory Connell, 21, was a graduate of Edgewater High School who worked at the College Park Publix where Fonzo shopped daily. He decided to throw a fundraiser at his restaurant for Connell's family to help pay for the funeral and other expenses. "[The evening] showed how, when challenged through devastation and loss, we can come together as one, regardless of race, religion or sexual preference," he says.

Nina Reynolds, UCF graduate

Nina Reynolds didn't come out as transgender until her third year at the University of Central Florida, but says other students and her professors were kind and understanding. But there were still odd looks on the bus, misgendering and an endless battle with the state's medical system. She says Pulse woke up many people in Orlando's LGBTQ community to the hatred still present. "There's a perception that just because gay people can marry and have a fire-ass parade every year that the fight is over. I feel it's barely begun."