Outside O'Horan Public Hospital in Merida, Mexico, the heat is crippling. Dozens of Mexican citizens wait for hours in blue plastic chairs just beyond the hospital's main doors to be seen by a doctor. The hospital is too small to have a waiting room, but sitting in the sunlight feels like baking in an oven. When the wind blows, it only gets hotter.

Inside the hospital, Winter Park plastic surgeon Dr. Frank Stieg works on his third surgery of the week. With his headlamp focused directly at his patient's mouth, Stieg leans over the body of 4-year-old Victor Dominguez. Only a thin cushion separates the boy's body from the rusty metal operating table on which he lies. His mouth is pried open with metal fixtures, exposing a gaping hole in the roof of his mouth and lip. Dominguez was born with a cleft lip and palate. His brown eyes have been taped shut, and he sleeps peacefully under a heavy dose of anesthesia.

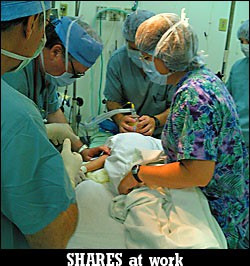

It's the first day of surgery for the Florida Hospital SHARES surgical team, and the mood is tense. Stieg's nurse, Joy Burke, walks into the room carrying a small Gatorade bottle full of clear liquid. The Gatorade wrapper has been torn off, and the word "bleach" written in black magic marker near the bottle's bright orange cap. For more than an hour, Burke has worked to keep the room clean and sterile while assisting Stieg during surgery. It's not an easy job.

"Anyone who kills a mosquito gets five points," jokes Burke, as a mosquito buzzes around her head.

Rust covers the green lamps overhead, and dried blood dots the operating room walls. On the ceiling, one light is burnt out. The remaining three are dim.

Without warning, a 15-year-old volunteer faints, hitting her head on the operating table on her way to the floor. Another volunteer sees her falling and moves to shield the patient from the blow. Burke and anesthetist Erwin Velbis rush to help the dazed girl to her feet. Everyone is stunned, except for Stieg, who doesn't miss a beat. Stieg is intense, and very serious about his work. Like an artist waving a paintbrush on a tiny canvas, his hands move quickly to close the hole in the boy's mouth.

An hour later, his surgery complete, Dominguez is rolled to a recovery room down the hall. As he wakes up from anesthesia, he is agitated and confused. His mother comes in to comfort the crying child.

When she turns the corner to see her son, tears of joy fall from her eyes. With the boy cradled in her lap, she weeps to herself for nearly an hour, gazing at her son's new face.

Stieg and his medical team are members of the Florida Hospital SHARES surgical program – a nonprofit international humanitarian health organization born out of the Florida Hospital Foundation. Four times a year, surgical team members donate their vacation time to repair cleft palate deformities on underprivileged children living in Mexico. Though it looks like an acronym, SHARES is actually just a name coined by Stieg's wife, Sharon (also a SHARES board member) that represents sharing with those in need.

"Members of the SHARES medical team have a reputation at Florida Hospital for being the 'best of the best' in their chosen field," says SHARES chairman Dr. Thomas McKean, a retired Navy maxillofacial surgeon who has been chairman of the SHARES board since the program's inception more than 10 years ago.

The SHARES teams alternate doctors, nurses and volunteers for each trip. The Merida surgical team consists of plastic surgeon Stieg, oral maxillofacial surgeon Dr. Wilbur Davis, anesthesiologists Drs. Robert Tainsh and Kevin Thoni, anesthetist Erwin Velbis, five nurses and 12 volunteers. Among the volunteers are the children of three visiting doctors.

"These trips are a great opportunity for us to show our kids firsthand what it means to help others," says Thoni, who brought two of his five children. "When we're all home, many of us have to work long hours at the hospital. So this is also great way for us to spend quality time with our kids."

Stieg, the surgical team leader for this year's nine-day Merida trip, has made 17 surgical trips in the last seven years. He was selected out of more than 300 Florida Hospital staff members for the 2004 Florida Hospital Foundation Volunteer of the Year award.

"I like fixing things, especially for children," says Stieg, who specializes in pediatric plastic surgery, as well as breast cancer reconstruction and cosmetic surgery.

Three hours before Stieg's nurses roll Dominguez into recovery, Davis is waiting for his first surgery of the day. Natalie and Tucker Thoni, the high school-age children of Dr. Thoni, stand in the corner of the operating room with wide eyes. They're among the half-dozen SHARES volunteers who'll be observing surgery – all of whom seem nervous.

A mask covers the bottom half of Davis' face. It's obvious that he's smiling – his eyes are a dead giveaway. With arms crossed, the surgeon waits patiently for anesthesiologist Tainsh to bring in the first patient.

Davis inspects a large trail of blood on the walls of the operating room. "They could always just paint the walls a maroon color to camouflage the blood," he says, chuckling.

Everyone laughs. The hospital staff has secured the wobbly light fixtures into place with white surgical tape. With all four lamps on, the light is still very weak. To the right of the operating table, nurses Candy Riley and Diane Van Luven organize and prepare the surgical instruments.

The door swings open, and Tainsh carries a small boy in his arms over to the operating table. The boy's name is Isaac, and he's literally "tongue-tied."

When the 6-year-old was born, the bottom of his tongue was attached to the inside of his mouth. The boy is only able to lift the tip of his tongue, making it difficult for him to speak clearly.

Isaac doesn't have cleft palate issues like most of the children scheduled for surgery this week. Davis took on the surgery because he knew it would be easy to fix, and life-changing for Isaac.

"When we assess the children for surgery," says Davis, "we always try to fix whatever we can while they're here, even if it's outside of the cleft palate issues we normally see."

Tainsh places Isaac on the table and prepares him for anesthesia. The small boy is scared, and Tainsh tries his best to comfort him, even though the boy doesn't understand English.

"Are they going to pinch me?" Isaac asks translator and SHARES coordinator Maria Blanchet, in Spanish.

"It's only going to be a tiny little prick, you'll hardly feel it," she says warmly, trying her best to keep him relaxed.

In less than two minutes, Isaac is sedated, and a tube is inserted into his throat so that he can breathe during surgery. Davis doesn't waste any time. He looks up at the young volunteers who are anxiously standing in the corner.

"Come here, kids, I want you to see this," he says. Everyone gathers around the table.

He reaches into Isaac's mouth and gently pulls upward on his small tongue. "See how it's attached? All I'm going to do is make a small incision underneath the tongue to free it up," he says, holding his hand out for a scalpel. "He'll still need speech therapy after surgery, because he's already learned to talk with his tongue attached. But this should make it much easier for him down the line."

Davis works quickly, and the volunteers brace themselves for the sight of the first incision. Some of them step away from the table. Some just turn their heads. After the first cut, everyone's bravery is restored. They watch the surgeon's every move, asking questions along the way.

In less than an hour, surgery is complete, and Isaac is on his way to recovery. The boy is groggy from anesthesia, and he's coughing profusely – his throat is irritated from the tube. The volunteers, who have all grown attached to Isaac, swarm around him as he's carried to recovery.

"It's all over, Isaac. You were so brave," says Blanchet in Spanish.

Davis stays with the boy until his coughing subsides and he's reunited with his mother. Then he makes his way back to the operating room for his next patient. Underneath his mask, he's still smiling.

INTERNATIONAL AID

In 1993, Thomas Werner – former Florida Hospital president and current Adventist Health System president – wanted Florida Hospital involved in international medical missions, so he established the SHARES program. Prior to 1993, Florida Hospital had no outreach for sophisticated medical missions. But hospital officials wanted to do the work because it would be a good way for residents to learn.

During the program's first four years, the trips were focused on rural medicine and physical therapy. In 1997, SHARES board members decided to add surgical and dental components to the trips, sending the teams to Jamaica, Guatemala, Brazil, Peru, Ghana, Honduras and Ecuador.

But it wasn't until 2001, at the urging of SHARES team leader Stieg, SHARES director Thomas Donnelly, Florida Hospital CEO Dr. Donald Jernigan and Florida Hospital assistant director for family practice residency Dr. Mark Olson, that SHARES' focus was narrowed to provide health care services and continuing medical education for four of the poorest states in Mexico: Yucatan, Chiapas, Oaxaca and Tabasco.

SHARES board members select cities by evaluating need, desire, support and potential for assistance. The cities must have at least one hospital with at least one plastic surgeon.

Today, the group makes eight trips a year to cities within the four Mexican states. During the four "rural" trips, Florida Hospital residents and physicians team up with Mexican physicians to treat conditions common among poor Mexican families. The other four "surgical" trips are dedicated to operating on children with cleft lip and palate abnormalities.

Worldwide, about one in 500 children are born with a cleft lip and/or palate, says Stieg. A quarter of those cases have a cleft lip alone, and 25 percent have both a cleft lip and palate. About half of the cases have only a cleft palate.

According to a study by the Centers for Disease Control, American Indians have the highest total rates of cleft lips and/or palates. Since many indigenous cultures live in Mexico, thousands of children are born with the disorder there each year.

Stieg says one-third of clefts are passed down through genetics. Certain prescription drugs, such as Dilantin, Retin-A or Accutane, as well as cocaine use, heavy smoking, high consumption of alcohol and exposure to pollution, have all been associated with clefting. But in the majority of cases, says Stieg, there have been no causes discovered for the disorder.

Most afflicted Mexican children are forced to live with their deformities for life, due to extreme poverty and limited access to health care.

"Cleft palate deformities can greatly limit the overall function of the mouth," says Stieg. "Those afflicted with the disorder have trouble speaking, eating and swallowing. Sometimes the hole in the palate will lead to nasal regurgitation, or food coming out of the nose."

Donnelly, the SHARES program director, says the Mexican federal health agencies cannot afford to fully fund surgeries for children with cleft palate.

"The health agencies in Mexico must prioritize where their money is going," he says. "There may be 15,000 children suffering from cleft palate, but 2 million in need of clean water and vaccinations. So the Secretariat of Health places emphasis on those programs that will help the most people. That's why a program like SHARES is so important."

Donnelly, who for 20-plus years worked as a diplomat in Mexico, says the purpose of SHARES is to create multidisciplinary cleft clinics that will continue treatments after the SHARES medical team has left. The clinics will consist of several doctors, including a psychiatrist, an anesthesiologist, a speech therapist, an oral surgeon and a plastic surgeon, treating each child on an individual basis.

"We're not just flying over there to close holes," he says. "We want to treat the whole child. We want this program to go on every day of the year, every week of the year, with or without our involvement."

The Winter Park Rotary Club helps SHARES by purchasing expensive medical equipment, making hefty financial contributions and networking with several Mexican Rotary Clubs.

The club helped raise over $16,000 for the Merida trip alone, money spent on supplying O'Horan Hospital with a full set of surgical instruments to use in cleft palate surgeries.

Winter Park Rotary also enlisted the help of Merida's local Rotary club, which was able to garner the support of high-ranking officials in the Mexican health agencies.

Club Rotario Merida Nuevas Generaciones also offered the group logistical support for the SHARES team during their stay – providing transportation, serving food and assisting with translations in the hospital.

"We only travel to places where we can partner up with local public health institutions or private organizations, such as a Rotary International Club," says Donnelly. "Without their assistance, we wouldn't be able to go there in the first place."

LONG DAYS

During the Merida trip, from March 25 through April 3, each surgery took up to three or four hours to finish, translating into long work hours for the team. They completed 43 surgeries during the week.

But Stieg and his team weren't the only ones putting in long hours. Nearly 100 children, parents and family members arrived at O'Horan Hospital seeking help – many of them traveling long distances to get there.

"Making a trip like this, if you're poor, requires an enormous effort," says Donnelly. "Many `of the visiting families` walk for hours by foot to reach a bus station, only to travel for another 10 hours by bus."

Maria Carolina Escamilla Cach, 22, traveled for three days with her 4-month-old daughter from the city of San Carlos, located in the neighboring state of Quintana Roo. This was her fifth visit to the O'Horan Hospital since December.

"The doctors here told me it would be faster for me to wait until the American doctors arrived to do the surgery," she says in Spanish. "I had to travel by passenger truck, bus and van just to get here and I didn't sleep between trips."

For parents like Cach, simple things like eating and sleeping can become nearly impossible tasks, and some traveling families arrive at the hospital without a place to stay.

"During the week, it's not uncommon for family members to sleep outside of the hospital, sometimes for days, while waiting for their scheduled surgery," says Stieg.

Despite the exhausting hours and harsh conditions, all of the families felt the trip was well worth the trouble. One by one, children were brought out of surgery with restored faces and placed in the arms of joyful parents. But perhaps no one was as content as Stieg himself.

"These trips are an incredible opportunity for us to change the lives of children forever," says Stieg. "Not much can top that."