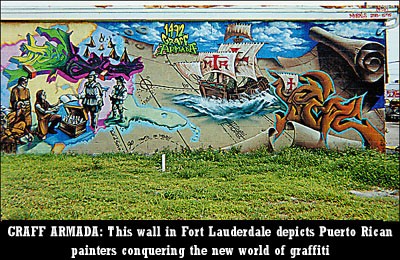

Antonio "Prisco" Ramos, 32, looks like a man who just ran into an old girlfriend. Standing across from his graffiti mural on the back wall of the Overflow Productions building on the corner of Hughey Avenue and Church Street downtown, he never takes his hands out of his pockets. Sweat beads on his forehead and the bright sun forces his blue eyes into a squint. As he observes his work, he seems conflicted; one minute he's peaceful, the next he's tormented.

In mid-February of this year, the managers of Overflow Productions, a photography studio, commissioned Prisco and his crew to paint the mural, giving them the artistic freedom to create whatever they wanted. The job was supposed to take three days; Prisco ended up working on it for two weeks.

"The only thing in life that makes me happy is painting," he says, breaking the silence. "It's where I find peace." After a few more minutes of staring, he approaches the wall and runs his hand over a colorful word painted in bending letters.

"These words you see at the bottom here, these are called 'pieces,' as in 'masterpieces.' That's what most graffiti writers start out doing." He pulls his other hand out of his pocket and runs his fingertip against a "piece" taller than he is. "This is my name. It says 'Prisco.'"

He pauses for a moment, and for the first time all afternoon, makes eye contact. "Prisco isn't my real name," he says with a Spanish accent. "No one in the graffiti world uses their real name. Prisco is a nickname my grandfather gave me in Puerto Rico. It means truth."

Just above the nicknames of his crew members – "Sex," "Ree2" and "Chain3" – an American flag covered with tombstones runs along the middle of the wall. At the top of the mural is a meteor knocking an elevated train off its track, into the American-flag graveyard.

"Somebody asked me if this wall was supposed to symbolize the war, and I told them it symbolizes the graffiti war," he explains. "Everything we do in graffiti symbolizes the graffiti culture. If I had to give this mural a name, it would be called 'Light Will Find a Way.'"

He puts his hands back in his pockets and nods toward the American flag. "The flag covered in tombstones symbolizes all the dying graffiti artists. There's a lot of beef and wars between different graffiti crews. Back in the '70s, when the movement started, graffiti was all about being against the system. This was a time when all the graffiti artists stuck together." He pauses for a moment, and his voice raises a notch. "But now that there are so many people doing it, they are killing each other over paint, and they are destroying other people's walls. Eventually, graffiti writers like me will have to find another place to paint. We're running out of walls."

He turns his attention back to the wall. "The train symbolizes the future – it symbolizes those who are trying to push us out. It symbolizes the barriers we face. But the meteor is knocking the train down. So the overall message is that no matter what they do, we're still going to find a way to paint. The light will always find a way. We'll never stop."

As he talks about his work, Prisco becomes more relaxed. He even smiles a little – a rare sight.

"Graffiti can make you a legend," he continues. "And the better you paint, the more colors you use, the more popular you become. Your reputation `in the graffiti world` is based on what you create. And if you're really good, you're considered a king."

STREET ROYALTY

In graffiti circles, Prisco is indeed considered a king. But fame comes with a price tag.

"Being a graffiti writer isn't as glamorous as it may seem," he says, looking straight ahead. "You're always traveling, you don't really have a home. You're lonely. Life is hard. My life has been full of struggle. But all the struggle fuels me to paint. And through painting, I find happiness. Even if it's only for a few hours."

Prisco was born in Manati, Puerto Rico, in a neighborhood where drugs and violence were commonplace. His escape was his art. His mother, who designed T-shirts, was his sole influence. He was 10 years old when he first picked up a spray paint can.

"Usually people who get their start in graffiti lived in New York during the '70s and '80s," he says. "They get experience from painting subway trains. But my influence was my mother. She used to make T-shirts at carnivals back in Puerto Rico. I grew up watching how my mother would make her shirts. I loved watching her draw out the letters."

When he talks about his mother, his face lightens. "One day I found a can of spray paint, and I tried to do the same thing that my mother did with letters on the walls of our garage. My grandfather spanked me because I accidentally spray-painted the car." He pauses and cracks a tiny smile. "So I used to sneak off to the nearby schools and practice my letters on the handball courts when no one else was around. In the graffiti culture, when you paint letters or names, it's called 'bombing.' There are different levels of bombing. A 'tag' is just a quick signature or a scribble. Bombing is more attractive, but you have to do it really fast, so you don't get caught."

Prisco remains perfectly still while he talks, as if paralyzed by memory. "At the time, I had no idea that the word 'graffiti' even existed, so I wasn't really aware that other people were doing this kind of stuff too. It wasn't until I was in ninth grade that I realized other people were doing what I was doing. And by this time, I already had my own style of doing things."

After years of practice, Prisco's bombing started to stand out among the rest. Soon his nickname and the nicknames of his friends appeared on random walls and school handball courts all over his city. He became a legend, but never revealed his identity for fear of getting in trouble.

"It excited me when people began talking. When you first start out in graffiti, you're not really good. But in your own head, you're an artist. You're already a king."

He moved to New York in the late '80s, and was amazed by how advanced the graffiti movement had become. Graffiti was everywhere, and it wasn't vandalism; it was art.

Other writers schooled him in the rules of the game. He learned, for example, that writers aren't supposed to buy their paint, they're supposed to steal it; he also learned that the more colors you paint with, the more your reputa- tion grows.

He also found out that to be considered a real graffiti writer, he had to spray-paint a subway train. He was jailed twice for doing just that.

People would see his work around New York and contact him from the information he left behind. As graffiti writers collaborated with Prisco, hip-hop event coordinators began taking notice, inviting him to paint at festivals and inner-city events. He ditched illegal painting and turned pro. The jobs started out small, and he worked as a flight attendant for American Airlines to make ends meet.

The highest-paying graffiti jobs were in Europe, where the art form is more widely accepted. Prisco traveled overseas and was soon getting sponsorships from European spray paint companies like Montana, True Colors and Belton. To date he has painted in dozens of countries, including the Netherlands, Canada, Chile, France, Brazil, Argentina, Slovakia, Mexico and Puerto Rico.

"The graffiti movement has really become a worldwide movement," he says. "And it's a lot more popular in Europe than in the U.S. Europeans are more open-minded about the art. Here they think graffiti is vandalism. And sometimes it is. But that's not what I do."

Today, Prisco's travel calendar is full. His walls have been featured in several books, including James and Karla Murray's Broken Windows and Burning New York – collections of photographs of New York's finest graffiti productions. He attends hip-hop events throughout the year, and when he's not painting for money, he's collaborating with other graffiti artists on murals. He also does urban advertising for products such as Big Red gum. In April, Big Red paid Prisco to travel around Florida to paint advertising walls for the brand.

These days, Prisco is able to support himself with his painting. The bigger the job, the bigger the bucks; paychecks range from $100 to $36,000 per wall. Airfare, food, lodging and paint are typically covered as well.

He paints with a crew who call themselves the "MTR clan." In English, MTR stands for "Minds to Reality." In Spanish, MTR stands for "Mi Tierra Represento," which means, "My country, I represent." Prisco is usually in charge. His crew members help create concepts and add their own touches.

The MTR crew claims to be the first graffiti crew created in Puerto Rico, by Puerto Ricans. Three of the original MTR members live in the Orlando area, including Willie Soto ("Wie"), Noel Olmo ("Sex") and Eric Bula ("Spec"), all men in their mid-30s.

"Next year, we will have been painting together for 15 years," says Prisco. "It's like a brotherhood. I love painting with my crew."

And the crew has several members from different states and parts of the world. "`Since our crew now has newer members from all over the world,` my walls are always different. We bring a message of unity and peace," he says.

He adds, "I never paint anything with a violent message, unless there is also a message going against it," he explains. "I like to play with people's minds."

BEEF

Money and travel notwithstanding, graffiti is not a particularly glamorous way to make a living, says Prisco.

"This kind of life is hard. You're always dealing with police asking you what you're doing. On every wall we paint, we're constantly having to defend what we do. But to me, this is art. We're capable of doing with spray paint what others are capable of doing with brushes. You can learn how to paint with a brush by reading a book. But with spray paint, there's no way for you to learn like that. Not everybody presses the tip the same way, not everybody has the same control. You have to love it and you have to practice all the time. There's no other way to study it. It's very difficult."

And of course, there are egos involved. "People get jealous, and it turns into beef. If you make it further than others, they're going to want your spot. It's kind of like rap, I guess."

One of the most common forms of disrespect in the graffiti culture is painting over someone else's work.

"People who are jealous of you will paint over your walls, or they write their name," he says. "The better you become, the more beef people have with you … . It gets lonely at the top. When I started, I didn't have any enemies or people trying to take my place. Now, I have many rivals, which is stupid. The only reason I do this is because I love it. It helps me forget and not think of anything else."

Turf wars and violence are often the result. In the summer of 2001, Prisco was painting a mural with a friend in Harlem when six men with baseball bats attacked the duo, shattering Prisco's leg and leaving both men in the hospital. The attackers were after Prisco's friend, but when Prisco tried to break up the fight, they beat him too.

"I have a metal pipe in my leg now," he says as he pulls up one pant leg, revealing a scar.

It's a good idea to know who you're dealing with, he adds. "It can be dangerous. Or people can use you or `rip you off`."

Prisco says a local man, whom he didn't want to name, coordinated two major jobs for him in Central Florida (one in Orlando), offering to act as his agent and even distribute pictures of Prisco's work. In return, the man wanted a cut of the profits. The man also agreed to let Prisco keep any leftover spray paint. But the guy failed to come through with his promises after the work was completed, stealing his paint and cutting off all contact.

"He just disappeared. I wasn't planning on staying in Orlando this long. I came here because I was hired to do work, but I ended up getting played."

Chris McEniry, head photographer for Overflow Productions, felt bad for Prisco and wanted to help him.

"We weren't the ones to hire him," says McEniry, "… but he definitely got shorted. We didn't want him to stop working, we wanted to keep it going. We liked what he was doing. So we pulled together some money and bought several hundred dollars' worth of spray paint for him."

Despite his bad experiences in Orlando, Prisco says he wants to stay here, at least for a while. "I am tired of traveling. I want to settle down. I want to get a job here. Painting clubs, painting whatever. Just as long as I'm painting. I want to make some money so that I can bring my mother out of Puerto Rico."

His face lights up for a brief moment. "I miss my mother. I haven't seen her in over eight months, but every time we speak, she asks if I'm happy. I tell her painting makes me happy. I send her pictures of my work so that she can see my happiness. So that she'll know I was thinking of her when I was painting, and hopefully she'll feel peace."