This book took shape with the premise that understanding the origins of someone's art is crucial to experiencing that person's imagery. The notion questions the modernists' posit of seeing the artist as a conduit through which art and meaning mysteriously flow. Art does not speak for itself. I doubt that it exists beyond the sensibilities of the viewer. ... This book offers a look at 62 self-taught artists who have made Florida their home. Their personalities and their art are as diverse as the Sunshine State. Preferring to risk failure rather than engage in exclusionary politics or cubbyholing, I assumed a pluralistic stance when selecting the artists. Time will tell which artists' works maintains a connection to society. ... These artists create in ways that are relevant to what it means to be alive. They are survivalists of the material world.

— Gary Monroe, from the preface of Extraordinary Interpretations, Florida's Self-Taught Artists (University Press Florida)

Who knew? Not as many people as soon will, once "Extraordinary Interpretations, Florida's Self-Taught Artists" comes off the presses for its October debut. Once again, DeLand-based documentary photographer Gary Monroe (author of "Highwaymen: Florida's African-American Landscape Painters, 2001") has had some fun, poking around his home state in search of artists who came to their muse all on their own, with no formal training or intentions. For each of the 62 artists chosen by Monroe, he has snapped a portrait and a piece of their art work, and written a brief-but-evocative biography; the write-ups are far from being comprehensive and serve as more of a lyrical sketch.

The result is a scattershot blast of imagery and insight into some of Florida's everyday, if eccentric people, who are artists in their own -- and sometimes very strange -- right: the elderly lady who lives for her church; the doctor's wife with a chilling secret; the long-haired dude shilling his wares roadside; the old man who shoots his gun off in the night.

Some of the artists profiled are better known in their circles and beyond -- such as Mary Proctor and Orlando's Keith "Scramble" Campbell -- and make a living selling their works. Most have created for years in obscurity, without any notion of compensation. Some of the artists are mentally ill or suffer maladies that necessitate caretaking. More than a half-dozen of them died during the final editing of the book, including Bryant Gowen of Sanford, whose gun works are featured on the following pages. But Monroe doesn't really care about expressing those particulars or about getting into a scholarly discussion of "self-taught" vs. "outsider" theory. There is an intelligent introduction to the book that covers "Some Principles," "Some Places" and "Some People," just enough to bring the reader into this specialized realm of folk art, without yawns.

Considering Monroe's intention to help understand the imagery that plays inside an individual's mind and how it comes to life via artistic self-expression, the reader then has the double-loaded experience of glimpsing the imagery that plays in the head of Monroe himself as he captures the artists' essence in his undeniably powerful portrait photographs -- and this is where Monroe's own special genius fortifies the objective.

Still, there is a sadness that sweeps through the 130 color photos; sadness for demons that haunt, for broken lives, for unspoken dreams. "Life is sad," Monroe says with a resigned smile, before questioning, "Isn't it?"

Indeed, and Monroe intuitively understands these "survivors of the material world" at the same time he compassionately trumpets their beautiful and unique self-expressions through his own art of choice.

Monroe will sign books from noon-3:30 p.m. Saturday, Nov. 15 at the "Focus on Florida Folk" event at Mennello Museum of of American Folk Art; (407) 246-4278. His books are available through the University Press of Florida (www.upf.com)

The following highlights six artists from "Extraordinary Interpretations," accompanied by excerpts from their biographies.

|

Susanne Blankemeier | |

|

"I learned how to keep secrets, even from myself," says Susie Blankemeier, referring to her youthful suspicion that her charismatic stepfather was involved in southern California's cultlike network of pornography and drug distribution. Living her youth in fear, she was unable to talk with her siblings about it, and isolated herself from her entire family soon after beginning one of her own. | |

|

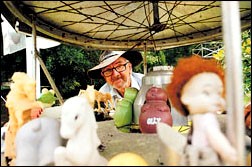

Aurelia Johnson | |

|

"Mama Johnson" acknowledges plastic detergent and shampoo bottles that have been transformed into dolls that she calls her "missionary girls going out to do good." She often talks to her dolls, mostly chastising them. "Ain't nobody going to want you," she tells them. "You're so ugly." ... Mama Johnson also draws "Aliestos," her endearing term for aliens. | |

|

Melvin Thayer | |

|

When Pop began collecting Social Security, he starting growing his metallic garden. The complex sculptures are cut from scrap aluminium. ... Melvin Thayer considers himself a "half-assed auto mechanic," not an artist. He says that he makes the whirligigs for his own pleasure. It's a hobby; he's not interested in selling the sculptures he creates. He adds that he doesn't want to worry about county officials looking over his shoulder for fees and taxes, either. | |

|

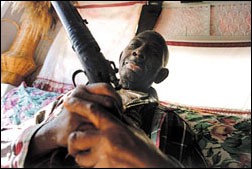

Bryant Gowens | |

|

Bryant "Bubba" Gowens made images of guns. ... He drew as many guns as he could fit onto the pieces of scrap plywood that he used. ... He added glitter to give the guns additional presence. ... He was not a violent man, but he did have guns, which were a part of his life since childhood. ... Gowens was known to "shoot up a box of cartridges a week" in his yard, reasoning that it might scare away anyone who might be lurking in the dark. | |

|

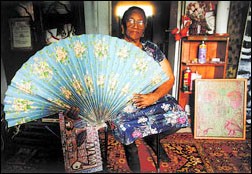

Alyne Harris | |

|

Alyne Harris ... compulsively mixes and feverishly applies paints to canvas boards, oblivious to the pieces she has produced once they are completed. Her subjects include landscapes, slaves, and churchgoers. She also paints "haints," devilish creatures whose open mouths sometimes reveal angels. ... "Beauty," she says in her turn-away voice, "is different for everyone. Somebody much likes lamb chops. I don't. I like chicken." | |

|

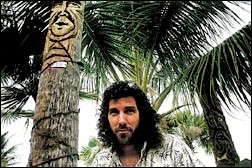

Ed Volonnino | |

|

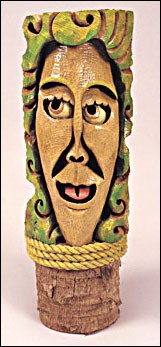

Ed Volonnino professes to have a "consciousness of trees." In order to carve his tiki heads, he has to know all about the sabal palms that he uses for his work. ... Volonnino has been an independent artist since 1981, selling tiki heads along the area's roadsides. ... His creations are secular. He doesn't mind, however, if a buyer prays to one of his tikis. ... He contents that onlookers'alcoholic consumption boosts his sales. | |

(photos by Gary Monroe)