During the November midterm elections, there was much ado about Amendments 5 and 6, two measures that were intended to alter Florida's redistricting process by forcing the legislature to respect municipal lines, balance racial representation and deter attempts by political parties to draw districts that favor incumbents. The amendments were approved by voters with a 63 percent margin, but since then, there has been a cacophony of concerns about them.

On Nov. 3, U.S. House incumbents Corrine Brown, D-Jacksonville, and Mario Diaz-Balart, R-Miami, filed a lawsuit to block Amendment 6 (defining U.S. Congressional districts), claiming that it violated federal law and could actually hurt minority representation rather than help it. Gov. Rick Scott muddied things further when he secretly withdrew the amendments from the U.S. Justice Department approval process in early January. Soon after, Florida House Speaker Dean Cannon, R-Winter Park, expressed concern about Amendment 6's constitutionality and filed a motion that the state legislature should piggyback on the lawsuit. Redistricting is expected to commence regardless, meeting the deadline of June 2012.

But that gerrymandering soap opera is only part of the story.

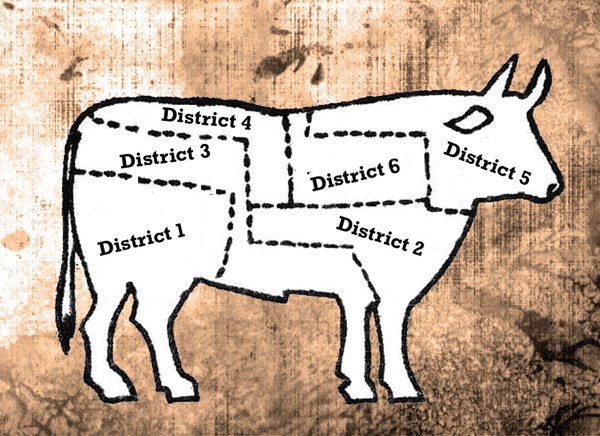

As with state legislative districts and U.S. Congressional districts, local county district lines, school board district lines and even the six non-partisan districts of the city of Orlando have to be redrawn in the coming months to reflect population shifts and growth. Though 2010 census numbers specific to the city have yet to be released, echoes of what was a contentious battle over race and representation in city government 10 years ago (the last time the city had to redistrict) are already resounding.

Substantial developments in Baldwin Park and Lake Nona's medical city may threaten a decade's worth of boundaries, and boom-and-bust foreclosures and empty condo units could shift the balance of power in some areas. At least one commissioner, Phil Diamond of District 1, may be pushed out of his district altogether when the dust settles. Which should be just fine by him - he's probably running for mayor in 2012. Local politics are about to get dirty.

Doug Head, former chair of the Orange County Democratic Executive Committee, knows the drill. He was one of nine members of the city's redistricting advisory committee in 2001; he was chosen by Commissioner Patty Sheehan to represent the interests of District 4 (each commissioner chooses one representative of the committee, the mayor will likely pick three). In 2001, the board included such luminaries as current Orange County Republican Executive Committee head Lew Oliver and, remarkably, Dean Cannon. The drill, Head says, amounts to little more than political theater.

"They don't need a commission or a board," he says. "I can tell you from my personal experience that the commissioners talk to the staff and the staff explains to the advisory board why everything needs to work the way the commissioners want."

In 2001, the city's population was just under 186,000 according to the 2000 census, and the ideal district population was determined to be 31,367. That population number is projected to grow by 15 percent when the current census numbers are released. The process of zig-zagging city district lines to approximate equality is one of exhaustive proposals and public input that will continue through the summer, leading up to a council vote that will most likely take place in the fall - just in time to meet the legally mandated four-month window that must exist between redistricting and municipal elections in the spring.

It might seem like simple math, but in 2001 it wasn't. Then-Commissioner Ernest Page of District 6 lamented that fact that his district had absorbed the predominantly white community of Metro West, telling the Sentinel in late 2001 (after the decisions were made) that "people are calling me and saying it's a conspiracy to dilute black voting power in this city."

That wasn't the only issue: Hispanic advocates were denied a majority in East Orlando's District 2. The affluent white homeowners of West Orlando's Rock Lake area - a cluster of homes known as Spring Lake Manor - were not able to hop Highway 50 (and Commissioner Daisy Lynum's District 5, which is home to many minority communities) to become part of District 3, where the likeminded community of College Park is located. Some business owners who found themselves in District 5 worked ineffectively to be separated from the blight of Parramore, which is also part of that district.

Significant changes were made in the municipal shuffle: Commissioner Sheehan ceded Baldwin Park to former Commissioner Vicki Vargo of District 3 (a position now held by Robert Stuart) and picked up numerous neighborhoods, including the area surrounding the Mall at Millenia, in the interest of supporting the city's two minority districts. She's hoping for more stability this time around.

"Basically, I was a peacemaker last time," she says. "I took everything everybody else didn't want, and it's been great. I mean, I had the most change last time. I'll work with anybody. I want to be amenable, but the only concern I've got - and Commissioner Stuart's got - is that we're all the way at the north part of our districts, so there's not a lot of room for us to be flexible."

And there's only so much flexibility to be had, according to Sheehan. She predicts a strong focus on keeping existing neighborhoods together, referring to a pre-2001 conundrum wherein Colonialtown was under the control of two different - and different minded - city commissioners.

"I think you should have one person you deal with, and if you're upset with the leadership as a neighborhood, I think you ought to be able to express that as a neighborhood," Sheehan says, noting that the neighborhood split was more than likely a political machination to dilute progressive voting. She will be running for a fourth term in 2012, but with district lines up in the air, she isn't sure how to go about campaigning. "I might not even get a chance to walk because I won't even know where to walk," she says.

Sheehan wouldn't have to walk far to be in Commissioner Phil Diamond's District 1. His home is bordered on two sides by Sheehan's District 4. For the past couple of redistricting procedures, she says, there's been an emphasis on protecting District 1 by connecting the Wadeview area and Delaney Park neighborhood through creative mapping, something she suspects may be impossible this time. As a result of the mapping, District 1 is an apparent misshapen blob with a tenuous connection to the rest of the city. At about 55 square miles, it's also roughly equal to half of the city in physical size.

"I have a really interesting district," Diamond says. "I have some parts of the city that were established in the 1920s, then you have some areas that were developed in the '50s, '60s and '70s. It's interesting to deal with a mix of neighborhoods. It's interesting to deal with a mix of issues."

Previously, District 1's most prominent feature was the largely unpopulated Orlando International Airport, but with the explosion of growth around the adjacent Lake Nona, the features of the district could easily change. In 2001, the Lake Nona neighborhood only had about 100 residents, all of them white. Surely that's changed, but Diamond isn't jumping to any conclusions, instead allowing that there have probably been demographic ebbs and flows in all of the districts. According to city statutes, should Diamond's home no longer fall in his district after reapportionment, he'll be able to serve out his term through 2014 but could not run for re-election. Diamond "hinted" to the Sentinel on Feb. 18 that he would likely be going after Mayor Buddy Dyer's seat in 2012 - all the more reason that the reapportionment process is taking a political turn.

And redistricting, at least from the city staff's standpoint, should be a reasonably clinical process including a "traveling road show" for public input. It should not be, as history has had it, contentious and overtly political.

"From the government's perspective, what we have to do is put those political agendas aside, ignore them and draw lines in a way that isn't based on the color of peoples' skin only," says Kyle Shephard, assistant city attorney and redistricting point-person. "The driving thing for us, the controlling operative issue, is as much equality in the number of people in one district to the other."

Just don't try telling that to somebody like Doug Head who has endured the process before.

"There's a thousand games and this is politics at its worst," he says. "I have always used the analogy of The Matrix. This truly is The Matrix. You may think you're in paradise, but this process determines the matrix on which we make all political decisions for the coming decades. If it's rigged, as it is very definitely going to be, people will not get representation."