Twenty years ago I spend a month in Haiti working on a feature I will sell to the Orlando Sentinel. While there, I contract dengue fever which nearly kills me, escape the poisoned tip of an angry hougan's knife and fall in love with the sweet, long-suffering people of Haiti.

Fifteen years later I hail a cab at the Orlando airport and strike a good chord with its Haitian-American driver, Jean Edmond, owner of the Orlando Taxi company, and start using his service exclusively.

On Jan. 12, 2010, the roar begins in Leogane, the doomed village deep in the gullet of the topographical dragon's head that is Haiti. It shakes the country to death. By February, when I can bear to look no more but cannot bear to look away, and no philosophy helps my heart, I call Jean Edmond. My hands ache to help and I have to go, I tell him. He is speechless when I ask if he knows anyone traveling to Haiti. I push. Finally he says, "It's very difficult there now. My brother Zacharie is a pastor and he's going, but … ."

But nothing; I run with it.

In the high-noon heat of the airport at Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, I sit atop two suitcases, each bulging with 50 pounds of aid. Curbside, Zacharie Edmond ponders the equation of seven people, hundreds of pounds of luggage and one small car.

Edmond, whom everyone calls Zacharie, is an Orlando pastor with the Body of Christ Church. He co-founded, with wife Angie, the Global Vision Foundation, a mission that serves the poor throughout the Caribbean, particularly their homeland Haiti and Port au Paix, his hometown. Longtime American citizens, the Edmonds are transforming a house in Bon Repos, a Port au Prince district, into a home for earthquake relief volunteers. Zacharie's counterpart in Santo Domingo gives us weary travelers supper and sleeping quarters.

Before dawn we are on the road to Haiti. Ten hours along we reach a depot filled with relief provisions offered free to any pastor going into Haiti. Because of exorbitant fuel costs and hellish road conditions, there are few takers.

Our little caravan has the benefit of Zacharie's 1989 Nissan truck and a driver so we provision. The old workhorse suffers a groaning load and a jerry-rigged cargo cover but we at last reach the frontier. A wave at an armed guard manning an iron gate suffices as a border check. We drive into ghostly beauty, with mountains and vegetation shrouded in limestone dust. The nearly impassable road is serpentine along the banks of Haiti's largest lake, lifeless Luc Azyeu.

Haitian border guards wave the crew into the country

Thirteen hours and 230 miles later we enter the country's pulverized capital.

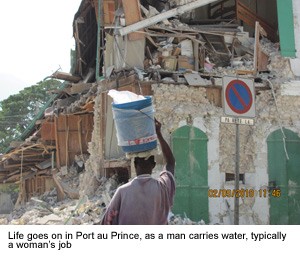

Diesel-blackened air hangs dark over collapsed buildings. Thousands of homeless men, women and children walk as though they have a destination. Amputees on crutches squint through smog and navigate gridlocked roads. A crazed grandmother who witnessed the unspeakable elbows her way, shouting nonsensically, "I am not a seller of milk!" Sidewalk vendors hawk consigned goods, from aerosol rubber to zippers. Vivid Haitian paintings startle, displayed on fences that separate tent cities from the streets. Sellers of charcoal arrange bags of Haiti's last stumps. Words on a wall lament, "Nou Bouke!" — "We are tired."

Gridlocked roads of Port au Prince teem with survivors

At quake time, nearly 60 percent of employable citizens were without work; unemployment compensation doesn't exist. The pre-quake daily minimum wage was about $3 U.S. — less than half the $7.25 hourly minimum in the United States. Exploited workers in foreign-owned garment factories earn the least, thanks to an agreement sanctioned by the United Nations and the U.S. In reality, most Haitians live on less than one U.S. dollar a day. With 90 percent of Port au Prince destroyed, most earn nothing, dependent on the diaspora to live at all.

The quake of Jan. 12 collapsed well-off lives alongside the destitute; homes — mansion and makeshift — lie flattened into tombs. At the home of a pastor in the now-crumbled affluent Pétionville district, we gather in a small courtyard, hushed by the account of a quake survivor's horrific loss.

She stood in the street for days, catatonic, staring at the crush of concrete that had been the three adjoining homes of her family and 18 others.

Beneath it was everybody but her.

She whispers, "My only daughter came from the Dominican Republic to visit me, to take me shopping. My son-in-law brought her and my two little granddaughters. We were just back from the stores. It had been a good day. My husband, my son, my son-in-law — all the men — were hungry. My daughter started supper."

Then the earth shifted and in 35 seconds all those lives were snuffed.

"But for me. I was not in the house. Why God not let me be in the house?" she questions.

The lovely lane that winds up to Pétionville's gorgeous landmark Hotel Montana is oddly intact, at first. A young marine stops us. We need clearance and must relinquish cameras. Behemoth equipment gingerly nudges massive rubble that hides countless corpses. Above the engine noise is a canopy of bated breath. We approach the section of the hotel that is partly standing — its lobby and dining room.

For 100 hours, Natalie Cardoza-Diedl was buried beneath eight stories of the hotel her family has owned and operated since 1945. Today she sits in a wheelchair, awaiting a flight to Germany where surgeons hope to save her legs. She is surrounded by ruined heirlooms, stacked chairs and scattered tables. Menus featuring barbecue and a band for Thursdays litter the floor. Behind her, slats of light shimmer through dangling doors once open to patio seating for al fresco dining and a panoramic view of Port au Prince.

Cardoza-Diedl's voice falters speaking of the still-entombed 35 staffers, her employees for four decades. "Unbearable! They were as family, and there is nothing we can do for their families because of insurance companies, which want us to prove everything, even that I exist! But how? All is destroyed!"

It is still unknown how many of the hundreds of guests perished.

By the front door, her sister Garthe talks anxiously on a cell phone, every breath an exertion. The Hotel Montana collapse crushed her adored 8-year-old grandson. "In public, now I only allow myself small tears because I know the enormous losses of other Haitians" — like the family reunion where reportedly 65 of 66 kin perished. "Now we are numb. In the months to come, we will be an entire nation lost in deep psychosis, with no psychologists to help us." Because there is no department of public health, most Haitians will never receive grief counseling, post-trauma relief, anti-depressants, sleep aids or therapy.

The drive from Pétionville across the rent heart of Port au Prince to Bon Repos descends into an end-of-days darkness. The country's pitiful pre-quake power grid is decimated. Tonight, the headlights of cars illuminate men shinnying up listing power poles, long thin wires dangling from their teeth. It is a Russian roulette attempt to clamp onto deadly tangles of high voltage wires, hoping for stray electricity. Suddenly, there are yells, people run, cars honk to move, everyone is looking up: Hanging high on a gutted building, a fiery segment of power line glows, threatening a flash fire. The pole men freeze. The segment sparkles, and then sputters out. The riggers exhale and resume their efforts to capture light.

"No infrastructure" is a toss-around term, seldom mulled by those who live with social order, but Haitians have lived for decades with no functioning departments of transportation, utilities, sanitation or environmental protection, to name a few. For first responders, the consequences of such awful governance were dire.

Now, in the gloom, we make out that the icons of Haiti's history are gravel: the national capitol, the national cathedral, the national archives, the national justice building and the national university. The symbolism is not lost on the populace.

Grand government buildings were demolished along with humble dwellings

Grand government buildings were demolished along with humble dwellings

Arriving at No. 4 Li Lavoix, I feel guilt entering Zacharie's safe haven for volunteers: I ought to be sleeping on rocky dirt with the soul-wounded.

The five-o'clock rooster outside my window coaxes the sun to turn a calendar of urgent days. Ferdinand Pierre-Val, Zacharie's right-hand man in Haiti, knows where to bargain for 100-pound bags of beans — not in the rank, infected public market, but among shop owners with swept floors and no rats. In the evening, we divvy the larder into large reusable bags.

Beyond the far-apart sites where on designated days able-bodied folks can queue for rice, beyond the remedies of scattered field hospitals, beyond the efforts of countless well-intended volunteers, wait thousands of the still-unreached and unattended. Val knows where to find some of them.

Nearly every dwelling on the road to Leogane is demolished. Miles of scrawled signs plead for aid. No traffic cones warn drivers of quake-chasms that could demolish a car. We stop to acknowledge an eerie memorial: Beside a deep gash in the asphalt a decapitated doll and her head lie alongside a willow's limb.

In Leogane, our little relief truck is nearly overrun by desperate refugees grabbing for aspirin, ibuprofen, bandages and detergent. Many are forced to camp near the cemetery with its old fractured monuments and its hurried new graves.

In the side of a sere suburban mountain a hole holds the anonymous bones of thousands. Grieving survivors are also here, living in tents, cobbling makeshift lives. On a tattered army canvas a scrawled cardboard sign advertises a generator-charge for cell phones. Women mend clothes and plait hair. Men in a line use broken hoes and plastic pipe to divert water from a far road.

The ingenuity of the Haitian people matches their resiliency

Young boys spy us and realize our mission. With grins and waves, they frolic alongside to receive bags bulging with beans and sardines, the first relief many of their families have received since their sad relocation.

From an adjacent scrubby hilltop three suspicious men watch us. When we reach the cluster of low, barred-window buildings, one man approaches and says he is the "director" of the place. He claims it is a shelter for pregnant women and homeless mothers with small children taken from the post-quake streets.

Zacharie explains our presence. The pitiful population stands back, listening. The two other men, sullen and holding sturdy sticks, glare and order the women and children into an obedient line to receive sacks of aid.

The little ones play with new balls and balloons. The bottomless sorrow in the eyes of the women who watch our departure defines the moment and a feared possibility: They are captives, with children and babies likely to go on the market.

They are called "restaveks," children who suffer deplorable damage as domestic slaves in exchange for meager meals and sleep pallets. At the time of the quake, there were at least 250,000 of them, two-thirds being vulnerable little girls enduring sexual abuse and rape. Their government doesn't record most of them as people.

In pre-quake Haiti, an estimated half-million children were orphans. Now the number has doubled. They are prime prey for domestic and foreign predators who feed the world's annual multibillion-dollar appetite for pedophilia and prostitution.

In the summer of 2009, fewer than 100 licensed orphanages served Haiti, a few with fenced yards, nursery-rhyme walls, trained staff and ownership by NGOs or churches. Others are good-hearted but bare-bone efforts by somebody with four walls and a roof. Many are nasty nooks, unlicensed and packed like fish tins with Haiti's most helpless. Now most are tent-or-tarp shelters, with one downtown tent location alone caring for 2,000 recent orphans.

A stranger directs us to the Upper Room Orphanage, a few miles from the mass-grave mountain. In an unfinished home, behind a stone wall and blue gate, it miraculously escaped serious damage and became a refuge when Joseph Pierre Josy and his pregnant wife, both teachers, offered to take in a single child. "After the quake, we stopped at 17; we cannot properly care for more," Josy says. Like most in Haiti, fear of aftershocks has the household living outside beneath a blue tarp.

We bring them beans on the day of their last rice. The children sing a welcome. We are escorted through the house. No electricity. No furniture. No plumbing. No water supply. No appliances. Jumbled piles of salvage are kept for now-homeless neighbors. On a wall, school lessons are chalked for children who'd never before seen the alphabet. We promise that Engineer Val will inspect the house for safety, and then we'll clean it, bring beds, keep them in beans and rice, and buy a proper blackboard.

Smiling, the children sing us away with a blessing. The tiniest girl waves a red balloon.

It was first-sight love; now each evening sisters Lili and Anoualle, 13 and 9, watch for my return. They are anxious for our ritual: We sit. They snuggle me. I point to words and they recite from a page of Creole/English vocabulary that I tore from an old travel guide.

Education is a craving among Haitian children. No public education system has functioned in the country for decades. Despite free-education mandates in Haiti's 1987 constitution, corrupt dictatorships have ignored the document's promise; further, countries giving massive aid, primarily the United States, have not demanded results and oversight. Consequently, over a half-million school-aged children have had no opportunity to attend school. Most who do don't make it past fourth grade. The paucity of public schools, which are not free, has unleashed thousands of fee-driven "private" schools, unlicensed, unregulated, often with unqualified teachers who have no more than four years of learning themselves. The best of these **petit seminaries** are attended by Haiti's more affluent students; 38,000 of them died in those academic halls so coveted by the poor.

The girls sit on broken desks in front of their collapsed school, which Lili attended for four years, Anoualle for two. Jarringly, their widowed mother approaches and beseeches me to take her daughters. It is their only hope, she says, to become educated, to have lives different from hers. "They are good girls," she says. "They will work hard in your house."

Anoualle and Lili are eager for any type of mental stimulation, as provided by writer Dee Rivers

A five-acre tent city sprawls across the hilly horizon. Curious children cavort around us. An aging monitor explains that a family's first food dole here consists of wheat flour, white rice and a tin of vegetable oil. After that, only rice, at two-week intervals. With few policemen, the place is a security and health nightmare. Scant protection guards unlighted nights. No toilets are here. Still, as we depart to the day-end clatter of U.S. helicopters, children and grownups move from their hovels toward a muddy clearing with hymns and prayers that lift into the gloaming.

The daily rituals of life continue in a dense refugee community

Somewhere outside at 5 a.m. Sunday morning, gospel voices sing: "Love lifted me … when nothing else could help, love lifted me." In this land of leveled lives, Haiti remains one of the most religious nations on earth. Elements of its national religion, Vodou, weave through most denominations. All day and into the night worshippers congregate in clearings or atop the remains of their churches. Pentecostals swoon, Catholics genuflect, and while holy men preach the unknowable mind of God and the balm of faith, the **hougans** conjure.

Pastor Jean Claude Silva stands on the ruins of his church surveying his flock. "You are hurting. The Lord knows the reason. Look up!" They do, eyes closed, arms aloft. Silva nods to boys holding brass instruments. The trumpet leads with middle C, a drum taps in, a saxophone and French horn harmonize, voices crescendo, "Do, Lord, oh do remember me."

Silva suddenly jumps and the dancing begins. The very old manage stiff shuffles. The children do little jigs. Men and women move with release and praise. Eventually the crowd is wrung out and grateful.

"Nobody has been here to see how we are doing," Silva says of his church's tent city ministering to 3,100 displaced survivors. "We've had no food distribution, and my people have lost so much."

Despite the devastation, church members gather in their Sunday best for a healing of gospel and dance

Beside him is Jonathan, a high school student who was buried under six stories of classrooms. "I was on the second floor. It gave way. I fell atop a dead classmate on the first floor. The rest come down. Next to me another young lady scream `that` her body pull apart. She never came out. In my grade alone were 120 students. Only five of us survived."

Silva moves to put his arm around Mark Lexon, whose wife, Denise, was quake-crushed at her ironing board while her babies slept nearby. The little ones were dug out alive. "I had to take one to the country for care," Lexon says, holding another tiny son. "This one, all he do is cry for he mommy, all the time he cry, ‘Mommy, Mommy!'" Lexon is now a widower with five children.

Widowed father of five mourns the loss of his young wife

Another woman shows me the nearby pallet where her mother clung to life for three days. "She ran to her bed when the shaking started, and the house fell on her," the grieving daughter says.

Some recollections are too terrible to relate, like the desecration of the dead by roaming, starving dogs.

As the service ends, Silva promises his people: "A tree grows from a seed planted upon rock, this rock." He points to his church's slab. "And nothing can remove it!"

Along a lovely bucolic road bordered by a bay putrefied with the city's raw sewage we find a country church with a small tent-clinic. Dozens of refugees have staked their body space along the church's covered walkway. They stand, jab the air and in unison order the devil away. We give the last of our medical supplies to the grateful young doctor who tends their ills.

Spirits hold strong among refugees at a rural church and clinic

Nearby, a Mennonite medical mission is rehabilitating amputees. We learn they will soon need local-knowledge drivers to deliver thousands of crutches and walkers to patients released back into their broken world. Val volunteers.

Later, at the end of our own road, we find more unrelieved bereavement. In a place ironically named the Valley of Silence, a woman sits before a pancaked house. Beneath it is her only child, a 16-year-old son. "If I could just hold his bones," she says, "If I could just lay them in hallowed earth." Down the street is parked a bulldozer that might help, but I never can find the owner.

By our 10th and last day, Zacharie, Val and I have handed several hundred people the first food and other supplies they have received since the disaster. Departing is difficult.

Passengers, mostly relief volunteers and traumatized, green-card Haitians, sit in quiet conversation as the jet touches tarmac in Miami. In that instant, from a seat in the last row, a woman's primal wail silences the cabin. As Marie St. Fleur implores God, those who speak Creole bow their heads. The rest of us brace for interpretation.

"Lord Jesus! When I leave here I have my arms around her, I come back with arms empty, empty. Give mercy, God, take me!"

Lovena Valliere, her funny, affectionate 15-year-old daughter, had insisted on accompanying her mother to Leogane — Marie's hometown — to visit sister Richemaine, 26, and nephew Shosie, his first birthday just passed.

Jan. 12 was filled with hair-braiding and sister talk. Shosie, in his new white onesie, had made the girls laugh as he tried his wobbly legs. Marie was visiting long-unseen relatives for the day. As Lovena and Richemaine chattered outside with friends, baby Shosie sprawled in sweet infant sleep. Suddenly, at 4:53, hell unleashed beneath them. Instinctively, they ran inside for cover, into the bedroom, tucking Shosie between them on the bed. Three days later, when neighbors unearthed them, they were still locked in futile embrace.

Now St. Fleur clutches a photograph of their found bodies and is compelled to show a stranger: "See what a pretty boy?" Shosie, his new onesie still remarkably clean, looks like he's just been put down for some tummy time, his dusty little head turned to his left. With her thumb, his grandmother rubs his tiny back on the image. Then, she tenderly moves her finger over Richemaine's face, as if to clear the heavy concrete powder. Finally, she gently brushes Lovena's apple-red blouse, like a mama removing lint from her girl's clothes before allowing her out the door.

Despite billions in aid, massive international effort and their own epic survivalism, the characteristic resilience of many Haitians is foundering. They are barely hanging on. They fear that even with foreigners promising a rebuilt country, old devils lurk in the details.

For thousands of homeless whose dwellings are roofless stick frames and cardboard, the specter now is flooding and mudslides. "All we can do," says a man, "is pray for Bill Clinton to hurry."

Late afternoon light moves into the troubled skies over Port au Prince. A ray's skinny shadow strides across the city's rubble and climbs a jumble of girders to finally perch on the demolished dome of the presidential palace. It is not hard to imagine that it is the shadow of Legba, the tricky Vodou guard of crossroads who can either offer good direction or mislead. His contrasting talents offer a cautionary tale for those who would be the builders of a new Haiti.

Finishing this story, I revisit for the first time my old Haiti file from 20 years ago and happen upon a tattered note. I vaguely remember a woman handing it to me in Port au Paix. On it she'd written a name and a Miami phone number. Now I stare at the name and am numb: Jean Edmond.

Twenty years ago I am too sick with dengue to follow up on her request and file the paper scrap. Fifteen years later I hail a cab at the Orlando airport and strike a good chord with its Haitian-American driver, Jean Edmond, owner of the Orlando Taxi company and begin to use his service exclusively.

[email protected]