It's a cold Monday night. The score is Falcons 28, Ravens 21. It's the fourth quarter, third down with 10 yards to go. The Falcons take their positions on offense, their muscles straining against their crimson jerseys, the Atlanta fans roaring appreciation for the home team. Just as quarterback Michael Vick is about to take the snap and zap the pigskin to running back Dez White, he realizes his go-to guy has been cornered by Ravens defensive powerhouse Ray Lewis. So Vick fakes out cornerback Chris McAlister to his left, and then cornerback Deion Sanders to the right, and decides to do the only thing that makes sense for a 24-year-old QB with blazing speed still holding the ball – make a run for the goal line.

But this football action is not going down at the Georgia Dome; though it's playing out on a screen, it's not being televised on ABC or ESPN. And the great fakes can't be attributed just to the quarterback. The glory goes to a long, lean young man sitting in a high-backed office chair deep inside a Baltimore mall. He goes by the name Big Game James.

Not only is James not running or passing or blocking, he barely moves, except for the calculated movements his fingers and thumbs make over a video-game controller. He doesn't cheer. He doesn't even seem like he's having that much fun. But he is so sure of himself that he knows that in this particular situation, if he pushes a certain button on the controller, his on-screen proxy will rush the remaining yards to a touchdown and victory. So he does something no player of any game should ever do – he turns his face away from the play in front of him, and looks at a console next to him, where a girl plays a game called Katamari Damacy. "Now that's a cool game," he says.

Vick gets the touchdown, just as Big Game James knew he would. "I've done that play a million times," he says with aplomb. "You know when you do certain things you're going to score."

The game Big Game James knows and plays so well is Madden NFL. Originally released in 1989, the hyperrealistic game took its name from former coach and current TV commentator John Madden and featured the likenesses and playing styles of real-life National Football League players and teams. Since 1997, EA Sports has released a new, ever more elaborate version of Madden every year. The most recent version, Madden NFL 2005, has sold more than 4 million copies since its release in August.

Madden has become something of a way of life for a network of enthusiasts who call themselves "ballers." The name comes, in part, from the name of the Baltimore club many of them belong to, but it also refers to the way the lives of these gamers mirror the football players they spend so much time studying and, via the game, being. The ballers tour the country playing Madden, they trash-talk, they note their opponents' strengths and weaknesses, they intimidate and psych out their competition and they often bring home big money, although instead of being paid by the NFL, they are paid by anyone who recognizes their game.

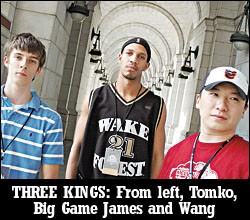

Big Game James' game gets recognized big time. A lanky 23-year-old from Pittsburgh known to his parents as James Lowe, he is the reigning champ of the Madden World Syndicate, an organization of Madden fanatics from all across the country. This past July, James won $3,000 and bragging rights at the MWS tournament in Miami. "There were over 300 people there, but I only had to win 11 games," he says cavalierly.

James says he spends about 20 hours a week playing Madden. The practice pays off, literally. He recently won $1,000 in a tournament in Charlotte, N.C., and he picks up cash here and there from people who like to bet on the games. While he won't let on exactly how much he makes playing Madden, James says it's "enough to pay for an apartment and a car," though he doesn't have many bills because he lives with his folks at their home just off Harford Road.

Still, he has to budget wisely. His reputation precedes him. "I can go a month at a time where people won't play me `for money`," he says. As Charles Wang, the 27-year-old owner of a video game store in Baltimore's Towson Town Square notes, "There are websites out there dedicated to ways to beat Big Game James."

EMOTION IS THE ENEMY

To give something back to the faithful, Madden distributor EA Sports sponsors the Madden Challenge, a nationwide tour where EA gives Madden fans in 32 cities the chance to play for a coveted spot as one of the finalists who will face off to win $50,000 in a tournament held in Las Vegas on Dec. 11. The tour recently made a stop at Washington, D.C.'s Union Station, and despite the fact that he is one of 512 players from around the Mid-Atlantic vying for that trip to Vegas and the finals, James seems more lighthearted amid a field of competitors than when playing a no-stakes game in his usual mall hangout.

"It takes a lot of luck and a lot of skill," he says of his prowess and success, with a half smile. "You need the breaks to go your way."

But Big Game James leaves less to chance in Madden than he lets on. For example, he always plays with either the Pittsburgh Steelers or the Atlanta Falcons, since he knows the Madden strengths and weaknesses of these two teams inside and out. He spends Sundays and many Monday nights at home watching NFL games, analyzing new plays and building on his knowledge of football to further his Madden game. He's more than just a student of actual gridiron action; he says he plans to try out as a wide receiver/cornerback when minor-league arena football starts back up in February.

"I love football so much," he says with something that resembles excitement. Excitement is not his usual mode when Madden is involved.

Over the course of five hours at the Madden Challenge, most of it spent in front of a game console, James shows very little emotion, despite the fact that during most games he blows away his opponents by tens of points. His demeanor is sullen, almost icy. At 6-foot-4 and built more like a hoops star than a football player, he towers over many of the other players. He usually dresses in a sports jersey of some sort, often in muted tones, which seem to echo his unfazed game play. He speaks in monosyllabic answers with the weariness of a star athlete being stalked by paparazzi. But there are no paparazzi here. When asked if he feels uncomfortable being interviewed, he says, "That's just the way I talk."

He has been playing the game since he was 12 years old, professionally for the last three years. He says he has learned quite a bit during his time competing, much of which can be summed up in four words: Emotion is the enemy.

"Being high-strung is a waste of energy," he says. "Makes me lose focus."

As James battles his way through opponents (he eventually makes it as far as the final four before being eliminated), Mike Brown takes a moment to reminisce. He was in the Baltimore Metropolitan Ballers when Big Game James was still battling puberty.

At 31, Baltimore Metropolitan Ballers "commissioner" Brown has seen the culture surrounding Madden boom, not to mention the business. Back when the Ballers started out in their own space, about 30 people spent their weekends crowded around 15 or 16 televisions and PlayStations in a 250-square-foot space lined with wood paneling, beige carpet and NFL posters. The clubhouse opened weekdays and weekends alike at 10 a.m. and would stay open until whenever – sometimes gamers kept going into, and through, the night. Brown says the Ballers' weekly $5 membership dues were enough to keep up rent, utilities and necessities. During tournaments – Brown says he tried to organize about three per year – more than 150 competitors paid a $25 entrance fee for a chance to win first, second or third place, with purses of $3,000, $1,000 and $500, respectively, though skilled ballers could make even more on the side bets that are common to the game. Brown says he put together some tournaments where the overall winner walked away with $5,000 in prize money, but even on regular weekends one or two top players might take home $500 apiece.

Brown says he understands why Madden players devote themselves to the game. "The game has a lot of realism to it," he says. "It's in the way the players move, the graphics. It's probably the most realistic video football game that's out," Brown says, adding that competitors such as ESPN Football don't even come close. Also, like another game that involves wagering – poker – there's another element to the game than what's happening in the actual game. "It's reading your opponent's `game`," he says, "trying to understand what he's trying to accomplish."

The gamers began traveling to other tournaments. In 1998, a national organization of Madden gamers sprung up in the Madden World Syndicate, founded by Israel "Swammi" Charles. Swammi developed a national standard of rules for play by which all ballers in the Madden World Syndicate abide; he now serves as the league's commissioner.

A teacher at Dillard School of the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale, Swammi has been playing Madden since 1991. He says his organization is comprised of men of all backgrounds and ethnicities. Madden World Syndicate hasn't had a female baller join yet, although Swammi notes, "We're waiting for that moment."

The same sort of technologies that provide for Madden's realism and complexity have made the national Madden World Syndicate league easier to build and maintain. Not only do ballers travel to play each other in person, they can log into dedicated websites and face each other down over the 'net. "I put the first known PlayStation website, aside from EA Sports, on the Internet back in 1991," Swammi says. "People started finding out about it from across the country. And when they found out that there are some other Madden junkies out there that had the same disease that they had, it just flourished.

"This game is very addictive," Swammi continues. "Men love to compete. And the adrenaline that you get from winning is a rush."

GAME TIME

Men love to compete so much that it has helped make video games a major industry. Overall U.S. video game sales topped $10 billion in 2003; by comparison movie ticket sales brought in $9.5 billion domestically last year. According to market research firm DFC Intelligence, U.S. video game sales are expected to near $17 billion in 2008.

Madden maker EA Sports, whose EA Tiburon Studio in Maitland produces the game, is raking in a sizable portion of those billions. According to EA's website, the company made $2.5 billion for fiscal year 2003. Madden NFL 2004 was named Game of the Year at the 2003 Spike TV Video Game Awards, beating out epochal and wildly successful titles such as Tony Hawk's Underground and the controversial Grand Theft Auto: Vice City.

The big business that is video games, and Madden in particular, has trickled down to the faithful. Brown eventually shut down his clubhouse in June 2004 so he could take a job as a zone coordinator running events for the EA Sports Madden Challenge.

As he chats, a loud clamor erupts from the other side of the station as the 32 semifinalists from the morning's games are announced. Only one of them will advance to the finals in Las Vegas, but caught up in their winning moment they have circled a fountain on the other side of the station to repeat the chant Raven Ray Lewis made famous – "What time is it? Game time!" – at the top of their lungs while jumping up and down.

INSULT TO INJURY

Big Game James took his nickname from former basketball star James Worthy, the low-temperature, big-results standout of the Los Angeles Lakers teams of the '80s.

Michael Taylor took a different but entirely appropriate tack for his game name. He was already known to friends as Curly Top for a long triangular wedge of hair that used to adorn his head before, he says, his barber "tricked me into cutting it off." He combined his existing handle with that of Nostradamus, the 16th-century French physician and astrologer whose predictions of the future are still widely pondered today. Thus, Toppadomis.

Walking into the Baltimore mall, Toppadomis struts like Jay-Z starring in his very own video. In fact, the 6-foot-4 Toppadomis bears a striking resemblance to the rapper, though he has just a little lighter complexion. He commands the room, as if sending the subliminal message, I am here – let the games begin.

Toppadomis sports mirrored sunglasses that go right along with his flashy clothes and gregarious personality, including plenty of trash-talking and jokes to go around. The contrast with introverted, insulated Big Game James could not be more stark. But later Toppadomis admits he's wearing the shades in part to hide dark circles under his eyes. He was up the night before until 4 a.m. playing Madden.

At 33, Toppadomis has nearly 10 years on Big Game James. Though his conversation consists of a near-endless stream of cracks and jokes, he's the first to acknowledge that not everything in his life has been a laugh riot.

"People wouldn't know it when I'm talking trash with these guys, and trading 'your mama' jokes, but I lost my mother, my father and my grandma at a young age," he says. Stone serious for a second, he adds, "I just probably blocked all of that out."

Toppadomis says he has been playing and betting on Madden NFL since 1990. "We bet on anything," he says. "We bet on whether or not the guy we're playing can get a first down, or a field goal or sometimes who will win the coin toss at the beginning of the game." Toppadomis has worked as a loan officer at a collections agency and as a retail-store manager, but notes, "I have made more money off of this game than I have in my career. And I don't seek out the money games. They just come to me."

His emotional, competitive style can upset opponents, especially those who lose. When he bested a competitor, he used to add insult to injury. "There's nothing more degrading than to take a man's controller," he says, laughing. "And what I would do is get into an SUV, run over my opponent's controller over and over again and keep the remnants."

Of course, Toppadomis has lost a few himself – defeats sting enough that he remembers the number of tournaments from which he's been eliminated: 15.

"I'm a much better loser than I used to be," he says. "I didn't use to lose well at all." Beat. "Actually, I still don't lose well," he says with a laugh.

TALKIN' TRASH

When Toppadomis shows up at the mall, he and Big Game James eyeball each other. They have known each other for many years, but they greet each other by trading simple, pleasant "wassup"s and get down to business.

James is the favorite to win, being the Madden World Syndicate reigning champ and all, but Toppadomis is still likely to make him sweat. Though Toppadomis has never won such a lofty title, he says it's coming. "Oh, it's a matter of time," he states flatly. "I went out in the final four in one `Madden World Syndicate` tournament in 2002, and final eight in 2001. So Big Game has got to watch his back."

Toppadomis plays with the Ravens and Big Game James with the Falcons. Their game is peppered with outbursts from Toppadomis when his Ravens can't keep on defense. He shouts out, "Come on, McAlister" and "Pro Bowlers, come on!" But Big Game James remains ice-cold.

By the time James' Falcons are up 14 points, Toppadomis has had enough. In the second quarter, Toppadomis gets Jamal Lewis to run for a touchdown to make the score 14-7. Toppadomis' defense holds tight long enough for him to make a touchdown in the third, and then they trade touchdowns until time expires with the score tied at 21. Big Game James wins the overtime coin toss, elects to receive and proceeds downfield to get that final touchdown – delivered by Michael Vick – to win.

"Ever get the feeling the computer is trying to beat you out?" Toppadomis laments, frustrated with game. "When you have two hands on the ball with a Pro Bowl corner`back`, and he drops it, you think, 'It's man against the machine.'"

Toppadomis does not use his typical trash-talking on James, however. He says later that he knows Big Game is accustomed to that type of behavior. So, Toppadomis takes another approach – reminding Big Game James of his former weakness.

"I remember tears coming out of this man's eyes for nothing," Toppadomis says, recalling his now-frosty opponent as a 19-year-old newcomer. "Every time I'd turn around, he was about to fight his best friend over a game."

Though his face clouds slightly at the remark, Big Game counters quickly with the story of the time Toppadomis cried in the parking lot of the Madden World Syndicate Championship in Los Angeles in 2003 after he was eliminated. "The worst thing about losing is you have to wait for everyone else to lose before going home," Toppadomis acknowledges.

James pushes back harder. Turns out, unbeknownst to Toppadomis at the time, his tears were captured for posterity.

"They've got you crying on DVD," Big Game taunts.

"And there weren't just tears," Toppadomis says with a laugh, compelled to tell the embarrassing truth. "I was actually making sounds."

FULL TIME JOB

Since he was laid off from his collection agency job in September, Toppadomis' only source of income has been Madden. And aside from the time he spends with his fiancee and three children, playing Madden is all he does. Right now he plays about 40 hours a week.

"When I play it's hard to keep track of time, because it's like being in a time warp. You play, and time just slips away," he says. "I played for three hours today and I got nothing done."

Most of the time Toppadomis plays at home. In the back room of his Baltimore apartment, where most folks might put a dining room table, sits a computer with a wireless connection. A 63-inch big-screen television hooked up to a PlayStation looms in the living room.

While video-game equipment dominates his living space, Toppadomis is aware of the dangers of letting Madden dominate his life. He tells the story of a guy who lived in Chicago whose Madden name was Renegade X. Last year Renegade X was trying to sell a "controllerment," a tiny customized plastic box that would identify and protect competitors' controllers in the confusion of a big tournament, to EA Sports. But Renegade X lost all of his money traveling from city to city trying to win the EA Challenge and peddle his product. When his wife took his son and left, he committed suicide.

"For me it was eye-opening, and it put things in perspective," Toppadomis says. "I didn't know Renegade X well, but when I found out that he killed himself because he didn't win the challenge and his wife and son left, I just went upstairs, got into bed with my fiancee and I just cuddled."

Realizing what he has just said, he adds, "in a thugged-out kind of way."

Toppadomis acknowledges that "a lot of guys have lost their wives and girlfriends behind `Madden`." But, he continues, "What women have to understand is – you know where your man is, he's there in front of the TV screen, not fornicating or trying to get high on crack."

Big Game James may show little emotion in his game, but it leaks out when he takes a quick break from battling Toppadomis to take a call from his girlfriend. "I love you," he says into his cell before hanging up. He says he and Parker are on what they call a "three-year plan" for getting married; they are now about a year and a half in.

Big Game James is enough of a Madden eminence that younger players look up to him. One of those younger players is 15-year-old Gino Tomko. They both favor the Atlanta Falcons, they use some of the same tricks, and they like the same go-to guy, Michael Vick. But James says Tomko already had game: "I didn't have to teach him that much."

Tomko says he failed his freshman year of high school largely because of playing Madden. He was banned for a while, although his father lets him play now, with restrictions. "I don't play as much as I used to anymore," he says. "I used to play about 40 hours a week. Now I play about 15."

In the three years that Tomko has been playing Madden, the last of which he has played competitively, he says he has only lost three games. That means a lot of bets collected, small and large. Nodding at a fellow high school student, Tomko says, "His mother thinks I'm a drug dealer, because I always have money." Tomko is able to travel to Madden tournaments because he can fund all of the trips himself. Plus, he says, "My dad trusts me, and I don't do anything stupid."

Tomko recently traveled to Philadelphia for a Madden Challenge tournament, and although he didn't make the playoffs in Vegas, he won enough games to surprise a lot of people. Or, maybe more to the point, the fact that he surprises people won him a lot of games.

"Everybody was looking at me like `I was` a church boy," he says. "People think that because I'm a white guy and I dress preppy that I can't play. Then they're shocked when I win."

A few Madden players who were being followed around by an MTV camera crew for a series called True Life also underestimated Tomko, according to video store owner Wang: "Gino kind of embarrassed them" by beating the show's reality stars. Tomko pulls out an MTV executive's card and brandishes it like it's his ticket to superstardom.

On the morning of the tournament in the mall, Big Game James is nowhere to be found. But there are plenty of other Madden maniacs to take his place. The grand prize today is $2,500, and Toppadomis starts the day feeling pretty optimistic.

By 3 p.m., though, things aren't looking so sunny. While Toppadomis finishes in the final four, he does not take home the prize. Tomko won. It's all part of his will to power, to be the next Madden champ. Part of his prize money today will go toward that goal.

"I have to win a city because I want to go to Vegas," he says. "I'm going to Kansas City on Nov. 15, and if I don't win there I'm going to California." He knows all of this is contingent upon getting at least C's in school – otherwise his father will shut him and his money-earning Madden mania down. "I used to fool around in school and I used to be a class clown," he says. "But now I've got to focus. It's all about the game."