Rob Greenfield is tired. He's lonely. He's having digestive issues. Worst of all, he's hungry.

It's late February, day 107 of the environmental activist's latest project: For an entire year, he's either growing or foraging all of his food. Since Nov. 11, every crumb he's consumed has been harvested from his garden or one of the community gardens he's created, or foraged from Orlando's urban center or the Florida coast.

As he stares at the molding coconuts he intended to turn into oil over the weekend, he can't help but think of how easy it'd be to walk down the street to grab a quick, easy meal at East End Market. But if he cracks, he'd disappoint his more than 500,000 social media followers.

This has been his toughest project yet, he says.

It's harder than the 104 days it took him to cycle 4,700 miles cross-country on a bamboo bicycle towing a solar panel-covered trailer while only allowing himself to drink naturally sourced water and eat unpackaged food. It's harder than when he flew one-way to Panama with no money and only the clothes on his back, his passport and proof of income (for border crossing) to prove he could backpack his way home to San Diego using the kindness of others. It's harder than the time he created a trash-bag suit and added an additional 4.5 pounds of trash each day for a month while living in New York City to raise awareness of the amount of waste each American generates.

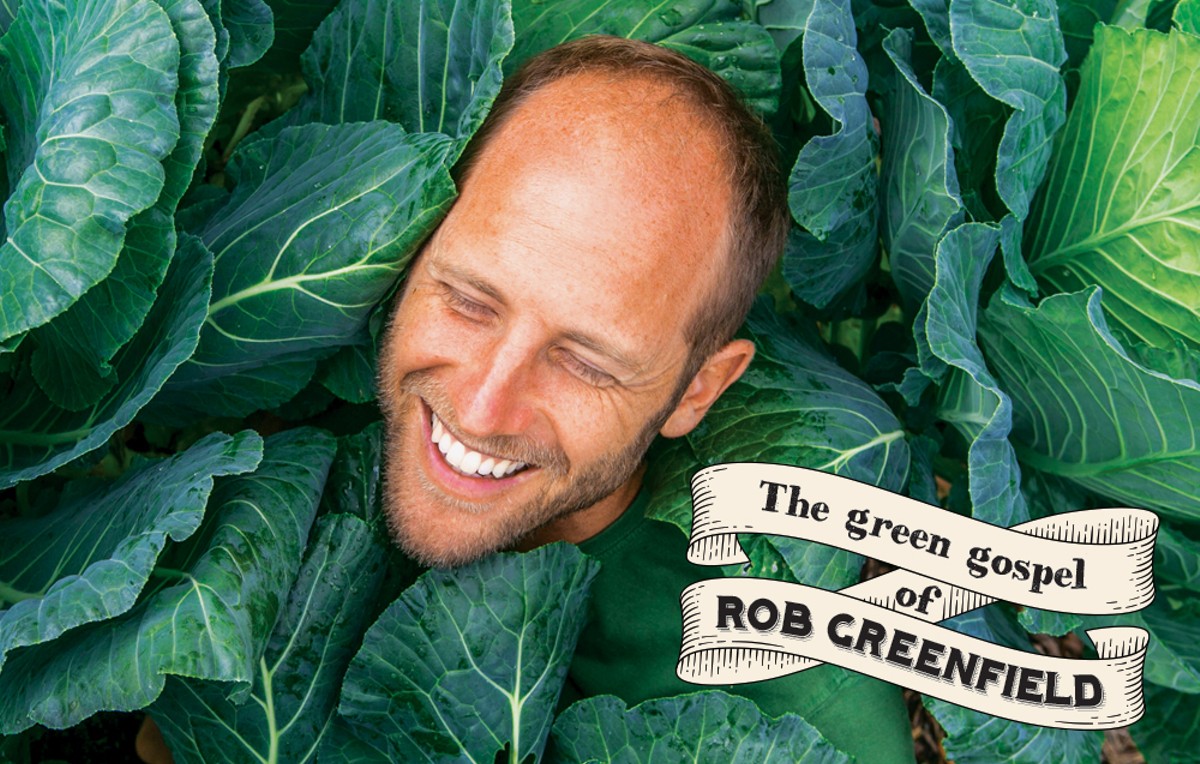

Sitting in a chair next to his 100-square-foot tiny house in Audubon Park, Greenfield pulls his knees up to his chest and hugs his shins. He's barefoot. There's a slight shadow of dirt caked into the wrinkles in his hands, stains from the time he spends digging through soil.

Greenfield understands why people consider him overzealous. He's a 32-year-old who says he only spends the meager money he earns through public speaking; who donated the $2,500 he made from his book Dude Making a Difference and the $30,000 he earned from his 2016 Discovery Channel show Free Ride, in which he trekked across South America with little money or planning; who got a vasectomy in his mid-20s so as not to contribute to a growing population; and who, despite a few unavoidable amenities, lives almost totally off the grid in suburbia.

"Some people look at me and think that maybe I think in a very extreme manner, and in some ways I do," Greenfield says. "But when you look at global norms, my life isn't extreme at all. The mainstream American lifestyle is what's extreme."

Opportunity brought Greenfield to Orlando.

He got acquainted with the City Beautiful in 2016 during a speaking tour. He and his former partner were looking for a place to move to from San Diego. Greenfield says he liked Orlando because it seemed open to sustainable change, and it needed it.

"It's that kind of middle area where I actually feel like I can make change," Greenfield says. "Chris [Castro] was like the perfect example of that, being the director of sustainability for the city and accomplishing so much with Fleet Farming," a nonprofit program that develops gardens on residents' lawns.

They moved here in December 2017, at first crashing with people like Castro and Sarah Robinson, the pastor at Audubon Park Covenant Church, who first met Greenfield at a potluck for Fleet Farming several years ago.

Greenfield asked to renovate Robinson's home garden in return for a place to stay for four months while they set up camp. She agreed.

"For me, the idea of bringing sustainability and helping people imagine a different way of doing life is really powerful and is definitely part of what my passion is at the church," Robinson says. "He's showing people what's possible and then inviting them to think about what things they might be able to change."

In the last year, Greenfield's launched three community projects: Gardens for Single Moms, which provided gardens to five single-parent families in Audubon Park (Greenfield plans to expand the program into "Gardens for People"); Community Fruit Trees, which has allowed Greenfield to plant 110 fruit trees in front yards, public parks and elsewhere; and the Free Seed Project, which Greenfield says has sent out 2,000 starter gardening kits.

Greenfield believes what you eat should reflect your beliefs, which is why he's taken on his latest project. But what exactly does urban foraging mean? Technically, you could forage through your pantry or fridge. Browsing a grocery aisle meets the literal definition of foraging as well. "Generally, what it means is that I won't eat anything that anyone else grows intentionally as food," Greenfield says.

He's nixed dumpster diving – for now – and won't let himself pick from someone else's garden unless he's working in it *(see note, end of story). But he does let himself pick fruit, or go to wooded areas to collect wild mushrooms and yams, or fish in a lake or ocean.

At its core the project is a protest of the global food system.

In 2012, America's largest factory farms produced 13 times more waste than does the human population, according to the nonprofit group Food and Water Watch. A report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations also found that consumers in wealthy countries waste almost as much food (222 million tons) per year as the entire population of sub-Saharan Africa consumes (230 million tons.)

But Greenfield doesn't expect everyone to follow his lead.

"My goal is to inspire moderation," he says. "I want people to start to live in a way that they feel really good about, where they feel in balance with their environment, with the earth, with humanity, and in a way that causes less harm to other people and species."

This is the paradox that defines Greenfield: To inspire moderation, he goes to extremes, even if costs him things – love, companionship – he says he values.

"The thing I struggle the most with is I'm very driven with what I'm doing, so that can leave relationships to be less prioritized, which is somewhat hypocritical because I value love so much, but yet can neglect it for ... my mission, my work," Greenfield says.

He adds: "When you're walking around [New York City] covered in trash for 30 days, it's not exactly easy to be making love and paying full attention to that person."

Greenfield stands up and walks over to the outdoor kitchen he's set up near his home. He starts slicing up a grapefruit.

The kitchen, built from reused materials, is nestled underneath an awning. From left to right on its wooden counter, there's a metal Berkey jug that filters his drinking water, a large blue 55-gallon barrel that's rigged with a hose to intercept rainwater from the top of the awning, a sink and a home biogas stove.

Connected to the stove is a hose that slithers around to the back fence. Situated about 20 feet away from the stove, it's connected to a "bio-digester," which acts like a stomach: Filled with water and bacteria, it breaks down food matter to a gas that powers the stove via the hose.

The water he uses is recycled rainwater, and not a drop goes into a sewer system. Instead, it filters into other places and uses, such as into the barrel on the kitchen counter, which he uses to wash dishes. (The leftover "gray water" from his sink is funneled into his gardens' banana plants planted along the back fence via a separate hose.)

Across the yard are two 275-gallon totes he uses to catch water from the roof of the property owner's home – the space was provided to Greenfield on the condition that he'd help the owner live sustainably and tend to her garden.

Next to the barrels is an "outdoor shower," though it's more akin to a place where he dumps a bucket of cold rainwater on himself from behind a fence-like barrier.

The inside of his tiny house smells like wood and Nag Champa. Using 100 percent repurposed materials and with the help of volunteers, it cost him less than $1,500 to build. Only 30 pounds of trash went to the landfill; Greenfield uses other leftover materials for fire kindling.

The shelves inside are littered with homemade goods. Honey wine sits on one of the top shelves in the corner, a product of the beehive he keeps in the yard. Next to it is a jug of Jun, a kombucha-like drink made from honey and tea. There are jars of fermenting kale stems, dozens of pumpkins and sweet potatoes, and a small freezer filled with more.

The wooden chair he got from a yard sale. His desk was made from scrap wood including discarded shipping pallets, as was his bed frame with storage built underneath. The flooring was recovered from a flooded home. The shelves themselves are from Habitat for Humanity.

Greenfield's house isn't insulated. In late January, when Orlando was at its coldest, he stuffed his clothes into gaps in the ceiling. The same cracks provide a breeze during warm weather.

There's no indoor plumbing; he uses an outdoor compost toilet that's situated discreetly behind the house – luckily the fence around the yard is tall. It's open-air and doesn't smell because he sprinkles sawdust over his waste; there's not a fly in sight. The toilet system is 100 percent closed-loop, meaning the 5-gallon bucket *(see note, end of story) underneath the throne's head collects the waste, which he turns into "humanure."

As a toilet paper substitute, he uses the leaves of the blue spur flower that's growing in the backyard. The plant is from the mint family, so it smells good too.

In 2015, the average size of new houses built in the U.S. peaked at 2,687 square feet, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Over 42 years, the average new U.S. house has increased in size by more than 1,000 square feet, up from an average size of 1,660 square feet in 1973, the earliest year data was collected.

"But we know for sure happiness has not doubled in that same amount of time," Greenfield offers.

Americans, indeed, have grown less satisfied with their lives in recent years. The Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index, which surveys Americans annually on their sense of well-being, found that 2017 was the worst year on record since the survey began in 2008, at the height of the Great Recession.

As a kid growing up in Ashland, Wisconsin, in the small two-bedroom house *(see note, end of story) he shared between his mother and three siblings, Greenfield dreamed of living in excess.

During summers in college at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, when he wasn't binge drinking and chasing women, he worked 80-hour weeks selling educational books door-to-door. He says he made a killing.

After finishing his degree, he moved to San Diego in 2011, where he and several others launched a marketing company. Then he left to start his own company, whose bread-and-butter product was hotel key-card advertising.

But an epiphany – what he vaguely describes as a waking up to how his actions were harming the environment – would bring all that tumbling down.

By February 2012, Greenfield had given up mass-marketed products, like deodorant, and switched to a mostly plant-based diet. Later that year, he sold his car and bought a bike.

In 2013, he began growing his food and got rid of his last pair of business slacks. He spent a week on the streets to learn about homelessness. He also embarked on what would be the first of three cross-country cycling trips he'd take to raise awareness about sustainability. Over a distance of 4,700 miles, he only used 160 gallons of naturally sourced water, created just two pounds of trash, plugged into five outlets without ever flipping a single switch, and consumed 280 pounds of food from grocery store dumpsters.

In 2014, he canceled his last credit card and paid off his last debt; finished a year without showering (he used water sources such as a leaky fire hydrant); and traveled moneyless for the first time. In that time, his message began gaining traction on social media as he traveled the country documenting his Food Waste Fiasco initiative, during which he ate solely from grocery store dumpsters for two months.

Greenfield was just getting started.

In 2015, he said goodbye to his phone, the last bill to his name; committed to rigorous standards for flying due to carbon emissions (he will only fly if it's for a good cause, such as a 37-stop speaking tour he did across Europe); and moved off the grid in San Diego to a 50-square-foot tiny house he purchased for $950.

In 2016, he auctioned off that tiny house for $10,000 (on the basis of his celebrity) and used it to build 10 tiny houses for the homeless; closed his bank account and decreased his net worth down to $3,600; and vowed to make no more than $5,000 a year and to have no more than that amount in possessions.

This isn't altruistic, Greenfield insists, and he's aware of how ludicrous his lifestyle sounds. But it's part of his commitment, he says, "to earn less than federal poverty threshold every year," or a little more than $12,000 a year for a single person, according to the 2019 federal poverty guidelines.

"Money is the simplest way of outsourcing our burden onto somebody else," Greenfield says. "If we need something, all we do is hand some money over and then we have what we need, and we don't have to think about where that came from, how other people were treated, the impact that it had."

Greenfield's also opted out of receiving health care provided under the Affordable Care Act. Given the amount of money he's made in recent years &ndash roughly $8,000 in 2018 – he'd qualify for Medicaid. But if he opted in, Greenfield says, it might damage his message.

"The problem is that by me accepting free health care, I risk losing legitimacy far too much from people that are my critics," Greenfield says, without mentioning who those critics are. "I don't want to give people an excuse to basically write off what I'm doing."

He spits out a seed from the grapefruit.

"So what do I have to do if I break my arm? I have a medical debt and I have to pay it off," Greenfield says. "My main health care is taking care of myself, and my secondary health care is that most things that I would deal with don't cost that much."

For all that's DIY about Greenfield, he doesn't make his own soap. A friend buys a natural brand for him and ships it to his post office box. He doesn't use it much.

"The reality is that if I was to wash that table with soap, I'm not really doing anything," he says, pointing to his outdoor kitchen. "So I don't use soap. You don't get the bacteria off the table when you use soap. It's one of those American delusions."

"Delusional" is a word Greenfield often repeats.

He's not delusional about the fact that the foods we eat can harm others, or that products like deodorant and lip balm are unnecessary to human existence (though perhaps we've developed to the point where we're permitted such luxuries). Neither is he delusional about death: In the worst of circumstances, such as cancer, Greenfield says he'd refuse chemotherapy and let nature take its course.

"That's the type of delusion I'm not buying into, and that's why I am very confident that if I need to die, I'm going to choose death," he says. "The way that I look at it is that if you believe life is important, then the best thing you can do is make way for that life. But by holding on as much as we can, what we're doing is we're killing future generations and giving them the worst quality of life."

It's not a happy take. Still, to scroll through Greenfield's social media accounts is to see a happy person, which, by all measures, he appears to be.

But he's always been different, his aunt Louise Greenfield says.

"Robin doesn't approach things like that with my attitude, like, 'Oh you're never gonna get anywhere near that' and 'You're going to look foolish to risk so much,'" she says. "He wouldn't think that way. He aims for the sky and maybe he reaches the sky, or maybe gets close to the sky, or maybe he doesn't get close to the sky, but he knows he tried."

Louise Greenfield points to a recent family tragedy as a testament to his impact.

Last month, in the middle of the night, Greenfield's mother's house in Wisconsin burned down. His brother, who lives there, was at work, but his mother was there and was forced out into a near-zero-degree weather without time to put on a jacket. They lost nearly everything, including the family cat.

The next day, Greenfield wrote to his followers on social media. He rarely makes requests online, but he asked them to donate to his family's GoFundMe.

"When I've seen so many people make donations of all sizes for my sister and one of my other nephews' benefits, it kind of shapes my assumptions about the proportion of humanity that's bad versus the proportion that's good," Louise says.

"I think Robin has attracted the attention and the respect of a lot of people and it's just so ..." She hesitates. "People have been so generous."

Greenfield's sister set $30,000 as the GoFundMe goal. As of press time, weeks after the incident, almost 500 people had contributed more than $18,000.

The green gospel carries far, it seems, as does Greenfield's ecstatic personality. It's a charisma that's inspired followers to take similar measures, from cutting down the amount of flights they take to investing more in homegrown gardening.

He's bringing much-needed awareness to issues of consumerism and consumption, says Tim Center, the executive director at Sustainable Florida, though his methods are "probably not for everybody." Center thinks that's a good thing.

In the long run, Greenfield isn't sure it will matter.

"I think most people, considering they see me trying, would assume that I think we can change the world, that I must have a positive outlook on the future," he says. "But the reality is that I think that it's extremely unlikely."

He leans back in the chair again, pulls his knees to his chest and spits another seed.

"It's meaningful because life matters. And so if we can have a positive impact on life around us, if we can make life better, if we can reduce suffering, all of that matters because life matters," Greenfield says. "But we shouldn't be delusional in thinking that making these small changes means we're living an environmentally friendly life, because none of us are living a life of regeneration. We're all living a life of destruction."

*Note: Some inaccuracies came to our attention after publication. Greenfield says "I don't eat from other people's gardens, even if I'm working in it. Only from gardens I've planted." He also says the two-bedroom house he grew up in was "more like two and a closet we turned into a bedroom, but we've always considered it three." And the "humanure" toilet uses a 5-gallon bucket, not 10. We regret the errors.