Heroin wasn't new to Stephanie Muzzy, but the batch she tried from Lake Downey trailer park near Union Park plummeted her into the depths of addiction.

In 2012, Muzzy was driving around Orlando looking for the worst neighborhood she could find in search of prescription pills. Pills were the reason she had left Boston six months earlier – she wanted to get away from the clique of friends who used with her. Living with her aunt and uncle in Florida, she was good for a while and had even gotten a job. Until, that is, she had a bad day.

At the trailer park, Muzzy couldn't find pills, but there was plenty of heroin. Eventually, the Orange County Sheriff's Office busted a heroin ring at Lake Downey where drug dealers were selling 2,000 bags of heroin a day. Six weeks later, Muzzy was sitting in the Orange County jail with a cracked face and a black eye. After quitting her job, she started shoplifting at stores like Plato's Closet to resell items or give them to her drug dealer in exchange for smack. Police arrested her after officers caught her stealing from a Kohl's. As she was detoxing during her nine days behind bars, she had a seizure and fell on her face. Her bond was only $1,000, but her mom wouldn't bail her out until she found a rehab facility.

"I was there almost three months. I thought once you went to rehab, you were cured," she says. "I didn't understand what it was. I lasted about six months before I started using heroin and Dilaudid again."

As the months turned into years, Muzzy was in and out of rehabs in Florida and Nevada, gaining and losing jobs, apartments, cars, cats and boyfriends along the way.

"I was doing well for a while, and I got a lot of my things back, so I thought it would be a good idea to go back home for a visit," she says. "On the first day, I did heroin again, and I overdosed in my friend's car. I decided maybe I shouldn't do drugs again, and I went home, but the obsession was still in the back of my head. It was all I thought about. I thought, 'I can just do one pill,' but it turned into me shooting heroin and Dilaudid about another year on and off. I couldn't stay sober because I was so miserable from losing everything I had."

Despite overdose after overdose, once even while on the toilet, Muzzy was able to recover – but the same can't be said for more than 2,664 Floridians who overdosed on opioids and never woke up during the first six months of 2016. On average, that means 14 people were killed by opioids every day, according to data from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, and those fatal overdoses are on track to significantly surpass previous years. Since 2011, the number of heroin-related deaths has escalated from 57 to a record 779 in 2015. During the same time period in Orange County, the number of heroin-related fatalities jumped from 14 to 85.

Fentanyl is currently Florida's deadliest drug. A state report from the Florida Medical Examiners Commission shows the manmade opioid, which is more potent than heroin, killed 704 people from January to June 2016. That's almost the same amount of deaths associated with fentanyl in all of 2015. While heroin-related deaths dropped slightly in 2016 in Orange County, deaths associated with fentanyl, carfentanil and other synthetic derivatives increased fourfold, from 17 in 2013 to 68 last year.

In February, Senate Democrats lambasted Gov. Rick Scott for paying quicker attention to the headline-grabbing Zika virus than the four-year surge of deaths associated with the opioid epidemic. Lawmakers pleaded with Scott to declare a public health emergency. Scott didn't do so until May. His declaration allowed Florida to immediately draw more than $27 million in federal grant funds and expand Scott's power to financially respond to the crisis without the Legislature's immediate approval.

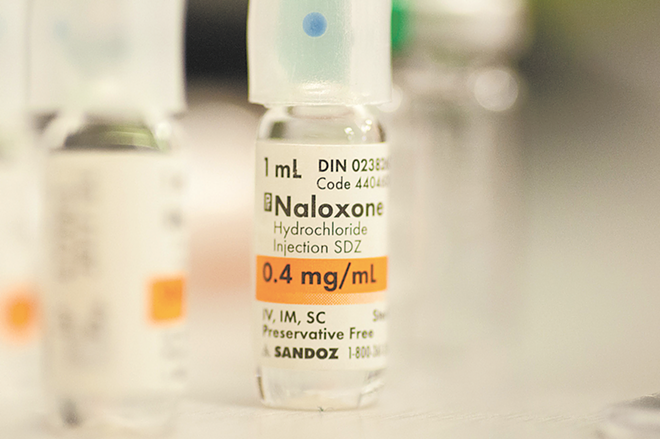

While the state administration figures out how it wants to address this health crisis, local governments across Florida, including Orange County, have already set up task forces and advisory committees to fight the epidemic at home. Law enforcement officials in Orange County were some of the first to start carrying naloxone nasal spray, an opioid overdose antidote. Meanwhile, at the jail, a pilot program for heroin-addicted inmates gives them access to a $1,000 shot of naltrexone, which blocks the effects of opioids. Local leaders launched a new website last month dedicated to spreading treatment and prevention information, and Orange County Mayor Teresa Jacobs has even testified about the crisis before Congress.

"We certainly don't want to say we're ahead of the epidemic because we still have dozens of people die every month, but we're glad we had the foresight a year and half ago to start addressing this problem," says Danny Banks, special agent in charge for the FDLE's Orlando region and a member of Orange County's opioid task force. "By making those recommendations and implementing them, this effort has already saved a lot of lives we probably would have lost."

Central Florida residents put a face to the opioid epidemic with the death of Victoria "Rikki" Siegel.

The 18-year-old daughter of Orlando time-share mogul and Queen of Versailles star David Siegel was killed by a prescription drug overdose in June 2015 after a stint in rehab. The teenager was found unresponsive at her home after ingesting a toxic mix of methadone, a synthetic pain reliever that can be used to treat opiate addiction, and sertraline, an anti-depressant.

By then, the epidemic had been ravaging victims in Orange County for about two years, as the deadly remnant of Florida's crackdown on pill mills in 2010. Without addressing the demand, painkiller addicts seamlessly transitioned from the dwindling supply of increasingly expensive prescription opioids to cheaper substances like heroin and fentanyl.

If the sudden jump in deaths weren't enough to alert officials that something dangerous was happening, the amount of heroin that Orange County law enforcement officers were submitting – from the small packets found on addicts to huge drug busts – quadrupled from 2010 to 2015, says Carol Burkett, director of the Orange County Drug Free Coalition. The county accounted for 844 heroin submissions, much more than Palm Beach, Miami-Dade or Broward counties. While fentanyl isn't a new drug, it is now cheaper to make than heroin, which is leading drug dealers to cut the drugs together, Banks says.

While the epidemic doesn't discriminate between race and social class, David Siegel's influence as the CEO of Westgate Resorts and the wealthiest person in Orlando pushed the conversation forward. Two months after the death of his daughter, Orange County debuted its heroin task force – one of the first of its kind in the state.

"I'm on a mission to save lives," Siegel told the task force at its first meeting in August 2015. "My daughter's death will not go without saving millions of lives if I have anything to do with it."

Six months later, the task force came up with a list of 37 ways to fight the heroin epidemic, which included equipping law enforcement with naloxone; increasing funding for detox beds and ambulatory detox; starting a social media and community communication campaign; advocating for increased access to naloxone for groups at risk; implementing a pilot program for heroin-addicted jail inmates to receive a dose of naloxone upon release and, if eligible, a naltrexone-brand Vivitrol injection to prevent an opioid relapse after detox; increasing bond amounts for heroin traffickers; and changing fentanyl's classification so that drug dealers receive minimum mandatory sentences.

"We must be tireless in educating people that addiction is an illness that requires serious medical treatment," Mayor Teresa Jacobs told federal lawmakers in 2016. "From law enforcement to families, the life-saving drug naloxone needs to be more accessible without a prescription and available at a reasonable cost. ... With a regional population of 2.5 million, we have only 26 beds for the uninsured. And yet 62 percent of the overdoses in our community are among the uninsured."

Police at the University of Central Florida were the first agency to carry naloxone in late 2015 after getting a grant for 150 doses. At the time, that made UCF one of only two universities in the country carrying the antidote on campus, according to USA Today. So far, UCF campus police officers have not had to administer a dose of naloxone as of last Thursday, says Courtney Gilmartin, a university spokesperson. The FDLE's Orlando office was the first state law enforcement agency to issue naloxone to agents and have it accessible at public entrances. Since first responders at the Orange County Sheriff's Office began carrying naloxone last summer, they've administered the life-saving medication 106 times.

"I oversee nine counties in Central Florida, and Orange County was the first to initiate this task force and stress the importance of issuing naloxone to first responders," Banks says. "It's a non-traditional role for police, this increased responsibility to carry something on them intended solely for the purpose of saving people's lives. But that's how bad this epidemic has become. Law enforcement may very well be the first ones to come into contact with an overdose."

Burkett says that while many of the recommendations have moved forward, there's still work to do. From 2014 to 2016, the number of babies in Florida born addicted to opioids increased from 1,903 to 4,215. That's a rate of about 18 infants with addiction withdrawals for every 1,000 live births. During the same period in Orange County, the number of addicted infants swelled from 158 to 327.

"We're not seeing as many heroin-related deaths in Orange County because law enforcement officers are carrying naloxone, which is absolutely saving lives," Burkett explains. "What we're seeing now on the street is a switch from heroin to mixing heroin with fentanyl. It's primarily from China, and it's 50 times more potent than heroin. Carfentanil, a fentanyl analog that's an animal tranquilizer, is 10,000 times more potent than morphine. No one really knows what they're getting in the bag that they're buying."

Burkett says the shift to stronger opiates like fentanyl means it might take more naloxone to reverse an overdose – a person might need two to three doses. Narcan, a brand of naloxone, costs $75 for a two-pack nasal dose for law enforcement officials, but paramedics can get cheaper prices on naloxone delivered through injections.

"Something I frequently hear the mayor say is that the reason Narcan is so important is that you can't get somebody help if you don't first save their life," says Carrie Proudfit, a spokesperson for the county. "Without naloxone, there's not even an opportunity for an intervention."

Banks says the task force's fight against the opioid epidemic has to include health services and treatment for addicts – to ignore it would cause a repeat of the surge in heroin and fentanyl use after the pill mill crackdown.

"Law enforcement officers can't just constantly displace drug addicts by moving them to just abusing a different kind of drug," he says. "There's going to be a different drug of choice two years from now, so we have to look at it from a rehab perspective and turning addicts away from their need to have any type of drug."

Many people still don't understand that addiction is a health care condition, says Mark Fontaine, executive director of the Florida Alcohol & Drug Abuse Association. Although lawmakers may not comprehend that funding for addiction treatment is needed, they're already picking up the tab without realizing it.

"There's a growing understanding in the Florida Legislature of the impact addiction has on the state budget," Fontaine says. "The cost gets played out in emergency rooms, in Medicaid spending, prison beds, juvenile detention beds and certainly in the child welfare system, where there's a tremendous pressure because of an increase in child removals from the home because of parental addiction. This epidemic is hitting all fronts."

Jeff Turiczek, CEO of Tampa's River Oaks Treatment Center of American Addiction Centers, says Florida's opioid epidemic could be dramatically affected if Republicans in Congress and President Donald Trump keep their promise to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Currently, the federal health care law gives low-income people with mental health problems or addictions the ability to afford preventative services, like rehab, through Medicaid.

"I don't think anybody goes in knowing an opiates addiction can be so expensive," he says. "There's never enough beds, never enough indigent care for the uninsured in Florida. It's a disease, and something that needs to be treated. It really is beyond somebody wanting to just give it up."

So far, state lawmakers' biggest accomplishment this year has been signing tough mandatory minimum prison sentences for people caught with fentanyl or carfentanil. The bill Scott signed last June forces judges to sentence people possessing 4 grams of fentanyl to three years in prison; 14 grams to 15 years in prison; and 28 grams to 25 years in prison. While the law is meant to punish traffickers, critics say mandatory minimums have failed in the past to reduce drug abuse in Florida and would likely lead to locking up low-level drug addicts – the very people the state says it's trying to help.

Despite the fact that thousands have died because of opioids, Florida has invested little in the epidemic and consistently ranks last among the states in terms of spending on mental health and substance abuse per person. Although the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is providing the state $54 million over two years for medication-assisted treatment and counseling for indigent and uninsured people with opiate addictions, the Miami Herald reports state lawmakers budgeted a mere $10.5 million this year on opioid-blocking medications, which will mostly be used by state prisoners. Advocates have not specified the amount of money needed to curb deaths, but for some context, the New York Times reports Ohio spent $1 billion last year to address its epidemic, and in April, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo committed more than $200 million to fighting opioids. Florida is also set to lose a $20.4 million federal grant for mental illness and substance abuse treatment, according to the Sun-Sentinel.

Orange County officials have pursued innovative methods to stem the tide of heroin and fentanyl overdoses, but if Florida lawmakers can't commit to funding treatment and prevention resources to help drug addicts, the skyrocketing trend of opioid deaths will continue on an unrelenting path.

Scrolling through Facebook, Stephanie Muzzy says she gets angry when she sees friends on her timeline calling drug addiction a "choice."

"It's classified as a disease, which is why health insurance pays for it," she says. "I didn't choose to steal from Kohl's and get arrested. Something in my brain makes me obsess and crave for it, makes me think, 'I'm going to steal all of my mom's jewelry today.' It's something pushing me to do horrible things just so I can get drugs in my body. I love my mom so much, but I know I've hurt her more than anybody in the world, because part of me is compromised."

When she tried to detox herself cold turkey last year, Muzzy had withdrawal symptoms that felt like having the flu, but 10 times worse. She was dripping sweat but freezing cold. For a week, she stayed in bed without showering, eating or sleeping. Muzzy was able to get up eventually, but the anxiety and insomnia stuck with her.

Finally, the 30-year-old decided to leave the destructive culture she was surrounded by in Florida for good and moved to Las Vegas again for treatment at Solutions Recovery. She's been sober since March 6 and has a new apartment, roommates and a job.

"Getting everything back is the best feeling," she says. "Losing it is horrible. I don't want to go through that again."

Muzzy realizes she's lucky to be here – she's already had at least 60 of her friends die after overdosing.

"I'm about to be 31 years old," she says. "I want to have a family, get married, have kids, go back to school, get my associate's degree. I want to do something where I can increase awareness for people and help them through what I've been through. The thing I would really want people to know is that if you are a drug addict, it's OK to ask for help. I was too ashamed and I didn't know other people were going through the same thing. But my mom never gave up on me. If she had, I would probably be dead."