The University of Central Florida thought state lawmakers would be sated with last week's ritual sacrifice of President Dale Whittaker. They were wrong.

Whittaker convinced the Board of Trustees this was the only way to get past investigations into the university's illegal misdirection of $85 million in leftover operating funds, which were used to build a $38 million replacement for a decrepit academic building known as Trevor Colbourn Hall. In a letter, he told the board that it had been "made clear" to him that, without his resignation, UCF would face ongoing recriminations from state leaders.

"I offered my resignation as a way to end punitive measures and threats, and restore normalcy to a healthy relationship," said Whittaker, who took over the position from retiring President John Hitt about eight months ago. "Florida needs a UCF that serves our students and community without fear of what the future may bring."

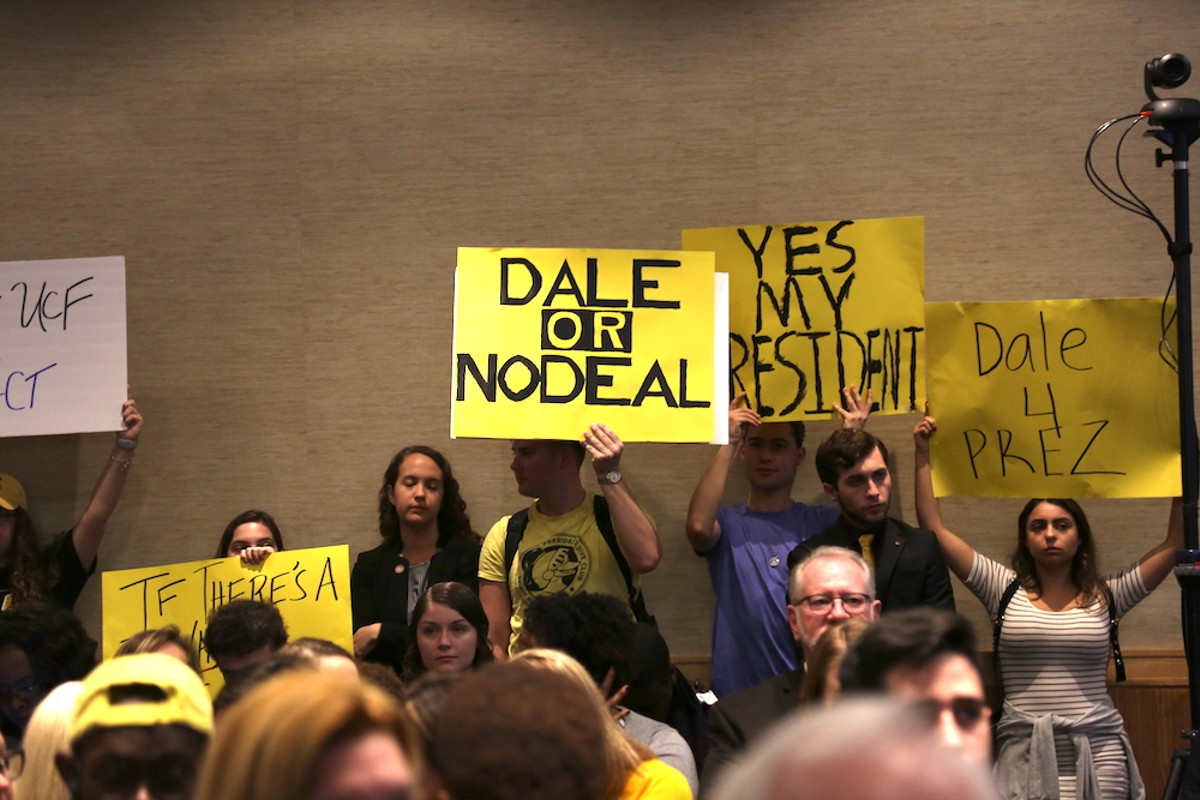

During 90 minutes of emotional speeches, tears and effusive praise at a Feb. 21 board meeting, some trustees fought the alleged injustice of Whittaker's resignation. His wife, Mary Whittaker, said threats were made to her husband and the school.

"In my eyes it seems that the state legislature is acting as a bully to force its agenda," Whittaker's daughter, Erin Whittaker, told the board. "To what end are you willing to allow this bullying to continue?"

But the board accepted Whittaker's decision to take the fall, hoping it would "heal new wounds."

"It's a tragedy for UCF that we're losing him," chairman Robert Garvey said. "His personal sacrifice, willingness to subordinate his own interests for the long-term interests of this institution are a credit to his character."

The potential consequences of not accepting Whittaker's resignation went mostly unsaid – except by Universal Parks and Resorts chief administrative officer John Sprouls, who voted against letting Whittaker resign, saying, "If by this vote it means I should no longer be on the Board of Trustees, I'd be happy to have that conversation."

For a moment, the bloodshed seemed to be over. But multiple investigations continue into what the school did, despite UCF paying back the money and claims that other state universities committed the same offense after years of steep budget cuts. Even though no one personally profited from building the 137,000-square-foot Trevor Colbourn Hall, state officials are hell-bent on showing universities what happens when you challenge their legislative financial authority – and they'll make sure everyone and anyone responsible pays a price. The vendetta against UCF seemingly held by lawmakers is similar to the grudges they hold against local governments, argues Rep. Anna Eskamani, D-Orlando.

"I can't help but make the connection to the vitriol UCF has faced as it relates to cities – especially those progressive havens with energy goals, efforts to protect immigrants and LGBTQ protections," she says. "The Legislature always makes an effort to pre-empt home rule. They're painting a picture of universities as villains, and it's the same type of attitude they take with local government. It's an exhibit of control."

Whittaker hasn't been the scandal's only casualty. Board of Trustees chairman Marcos Marchena resigned and four university administrators have been fired since the issue with Trevor Colbourn Hall first arose last summer.

That's when the state auditor general's office discovered that UCF had budgeted $38 million to replace one of the campus' oldest buildings after problems with mold and structural issues led officials to deem it a public hazard. But the money came from leftover operating funds, which are prohibited from being used to fund new construction. State policy restricts their use to instruction, research, libraries, student services or maintenance.

In September, UCF officials admitted to the misuse of funds to the state Board of Governors, which oversees public universities in Florida. Whittaker terminated four employees after UCF hired a law firm to investigate. UCF chief financial officer Bill Merck resigned, accepting "full and immediate responsibility" for the improper funding.

But transcripts from his deposition with Florida House investigators reveal how he really felt.

"I think the chairman and the president felt a need to show action in response to the things ... and they wanted to, for lack of a better term, to produce some scalps to show," Merck testified, adding that Whittaker's snap decision to ax four employees was meant to shift attention away from the possibility of blame falling on himself. "And these four people were on the receiving end of that unfairly," Merck said.

Whittaker suggested he resign. "And that was it, the end of a 22-year stint at UCF. Plastic bag in my hand with pictures of my wife," Merck testified. "It was – it was pretty brutal."

A subsequent investigation by the Florida House Public Integrity and Ethics Committee found that UCF had a "multi-year strategy" to misdirect nearly $85 million in leftover operating funds from 2013 through 2018, including the $38 million for Trevor Colbourn Hall.

The UCF investigation found that Whittaker, the university's provost from 2014 to 2018, knew leftover operating dollars were being used to build a new Trevor Colbourn Hall, but he didn't know of the prohibition against it. The president and Merck were stripped of tens of thousands of dollars in bonuses as a result.

Whittaker, Merck, Marchena and Hitt were subpoenaed to testify before the House committee led by Rep. Tom Leek, R-Ormond Beach.

Leek says his committee's final report on the UCF investigation will be done in about two to three weeks, and it's expected to reveal more fund misdirection and detail the infighting that led to Whittaker's resignation. Hitt has so far refused to give any testimony and has only offered written responses.

The probe has consumed a tremendous amount of resources, so investigations into funding misuse by other universities have not started. Politico reported last week that the House committee flagged 23 university building projects amounting to more than $252 million in the 2018 budget that may have been funded with leftover operating funds at multiple schools.

Asked about the dwindling state funds that may have caused some schools to improperly use leftover operating funds, Leek says UCF still broke the law. The Legislature's Public Education Capital Outlay, commonly known as PECO, funds construction and maintenance projects at public universities, colleges and K-12 school districts. The Orlando Sentinel reports PECO funding declined to a low of $73.5 million in 2012 after the recession, despite growing enrollment. In 2018, Florida lawmakers approved $487 million in PECO funding, with the 12-university system receiving $112 million in individual projects and $47 million in maintenance funds.

"You have to work within the system you've got," he says. "They constructed a building instead of conducting maintenance all those years. ... UCF has plenty of money to do everything they need to do lawfully, they just didn't want to do that."

Aubrey Jewett, an associate professor of political science at UCF, said the Legislature is "somewhat responsible" for the mess.

"They did not provide a reliable source of money to replace the steadily diminishing PECO funds traditionally used for [new buildings and infrastructure], and yet still expected the universities to accept more students and figure out a way to build new buildings and replace older, unsafe buildings," he says.

"And of course the Legislature is hypocritical in that they often have used earmarked funds for different projects than originally intended, like the practice of sweeping up money designated for low-income housing," Jewett adds, referring to lawmakers' frequent diversion of funds from the Sadowski Affordable Housing Trust Fund for other unrelated projects – something that's legal for the state but illegal for universities.

An ongoing probe by the Board of Governors could also uncover more misspending at UCF all the way back to July 2010.

"The Board of Governors is continuing to further investigate the university's other used and planned uses of education and general funds for construction projects beyond the construction of Trevor Colbourn Hall," Board of Governors spokesperson Brittany Wise said in a statement.

The four employees Whittaker fired in the early stages of the Trevor Colbourn Hall scandal are demanding their jobs back and say they wrongly took blame for a "broken culture" of misspending that Whittaker created. Whittaker did not respond to a request for comment.

"UCF would begin the healing process by giving these women their jobs back," says attorney Charles Greene, who is defending three of the employees. "Merck admits that he and others were involved in the decision-making process – not these lower-level employees who didn't have any input into the decision at all. They've just been blamed for it."

"I just hope UCF does the right thing, because if they don't, they will be sued," Greene adds.

The scandal plaguing UCF had been going on for months, with Florida lawmakers berating school officials throughout the process, but things started feeling like a personal vendetta when one legislator threatened to shut down the entire university for a decade.

In February, Rep. Randy Fine, R-Palm Bay, actually suggested that the largest school in Florida, with 68,000 enrolled students, should be shut down for five to 10 years. The Brevard County Republican made the comment at a hearing of the Florida House Higher Education Appropriations Subcommittee.

"I believe that we are stewards of the taxpayer money," Fine, the committee's chairman, told UCF's interim vice president for finance and administration, Misty Shepherd. "We are obligated not to fund organizations that refuse to steward that money in an appropriate way. If this a private business that I owned, I would shut it down."

Fine then asked Shepherd: "I'm working on a five- and 10-year potential shutdown of the university, and so how much money ... do you believe you would need next year if next year was the first year of a five- or 10-year shutdown because the university refuses to put in place appropriate corporate governance?"

Hours after that meeting, and with House Speaker José Oliva downplaying Fine's threat, Fine backpedaled, saying his comments were hyperbolic because he wanted to raise awareness of the serious nature of the investigation.

The damage was done, though, and some Orlando lawmakers began to question why their colleagues seemed so vindictive toward UCF.

Eskamani has a dual-degree bachelor's and master's degree from UCF, and is currently in the public administration school's Ph.D. program. Eskamani, who has also been an adjunct professor at the university, says she remembers taking women's studies classes at the old Trevor Colbourn Hall.

"This building was dangerous," Eskamani says. "Their only option was to tear down the building and rebuild."

Systems of government reporting allowed the misuse of funds to happen without oversight, and checks and balance are needed, Eskamani says. But she argues things got out of hand with threats to the university, which is an economic hub for Central Florida.

"We've seen lawmakers villainize UCF and try to use UCF as an example of the Legislature's strength on accountability," she says. "There are plenty of examples of hypocrisy where we're not holding ourselves accountable in the same vitriolic nature that continues to be exhibited toward UCF."

Eskamani wonders whether the University of Florida or Florida State University, two of Florida's pre-eminent universities with dozens of alumni in the Legislature, would be treated the same way as UCF.

"We now know that other universities may have been doing the same thing, so I ask, 'Are you going to shut down UF for five to 10 years?'" Eskamani says. "I don't know if UF would have experienced the same treatment because of UF's political power and number of grads serving in the Legislature. ... These are public universities that are part of our system of impact in Florida, and we're treating them like evil players in some sick game when they're trying to make the best out of limited resources."

Rep. Carlos Guillermo Smith, another Democrat from Orlando and a UCF grad, says lawmakers need to consider "what factors have led to this systematic misuse of funds at multiple universities, not just UCF."

"I'm worried that we're not looking at the systematic problem, which is the underfunding of public school buildings at our state universities," he says. "We need to address that as part of the response. Not just punitive measures that punish students and faculty that have nothing to do with these problems."

Smith and Eskamani have been the most outspoken UCF graduates in the Legislature in defense of their alma mater. Republican UCF graduates, though, have remained mostly silent. Orlando Weekly reached out state Reps. Amber Mariano, Rene Plasencia and Chris Latvala, all UCF alumni, but received no response.

The only vocal Republican UCF graduate has been Leek, who chairs the powerful House Public Integrity and Ethics Committee that's currently investigating the school. Leek says he's seen no signs of bias toward UCF. Although the University of South Florida also admitted misappropriating $6.4 million in leftover operating funds, UCF's $85 million misdirection of funds is significantly bigger, Leek argues.

"I love UCF," he says. "I hate what they did because it was absolutely wrong, but they're not being unfairly targeted in any way. ... Any wound UCF has suffered is self-inflicted. Any trouble they've gotten themselves into is because of trouble they've caused. Dale Whittaker is a good man. What he did was step down for the sake of the university, so the university could put a new face going forward. I happen to think that was the right decision."

Scott Launier, an associate professor at UCF and the president of the United Faculty of Florida at UCF, says the scandal is a "violation of public trust and taxpayer funding" and that a culture of misspending further impedes legislative trust.

"Once we get to the bottom of all of this, are we pursuing accountability strongly enough? I mean, this is criminal stuff. This is a really big deal," Launier says. "But I think that there are other people that are behind this that have not been named and touched by it yet. Because it seems that whatever agenda the university has had for the faculty union has not changed or wavered at all."

In the wake of reports last week that at least a quarter of Florida's universities have some issue with the improper use of state dollars, Fine struck a more measured tone, telling the News Service of Florida that he wanted to look at more training for university officials who oversee school finances.

Fine, a Harvard University graduate, says "nothing could be further from the truth" about lawmakers favoring other universities.

"I understand where that concern comes from, but I didn't go to any of these schools, so I don't have any affinity," he says. "If the University of Florida and Florida State had stolen $80 million, I'd be just as mad at them. ... I don't know that there should be any punishment for UCF. There should be appropriate actions for people who caused the misappropriation, but it's not students' fault."

Eskamani, though, says UCF students and staff would be directly affected if the Legislature refuses to provide for needed remodeling projects or allow the university to create a planned $40 million scholarship fund.

"I know it's not over," she says. "Whether it's removal of individuals from positions of leadership or lack of funding during this legislative cycle, it's definitely not over."