"My work is very quiet. I kind of like being almost so subtle that you might miss it if you aren't paying attention."

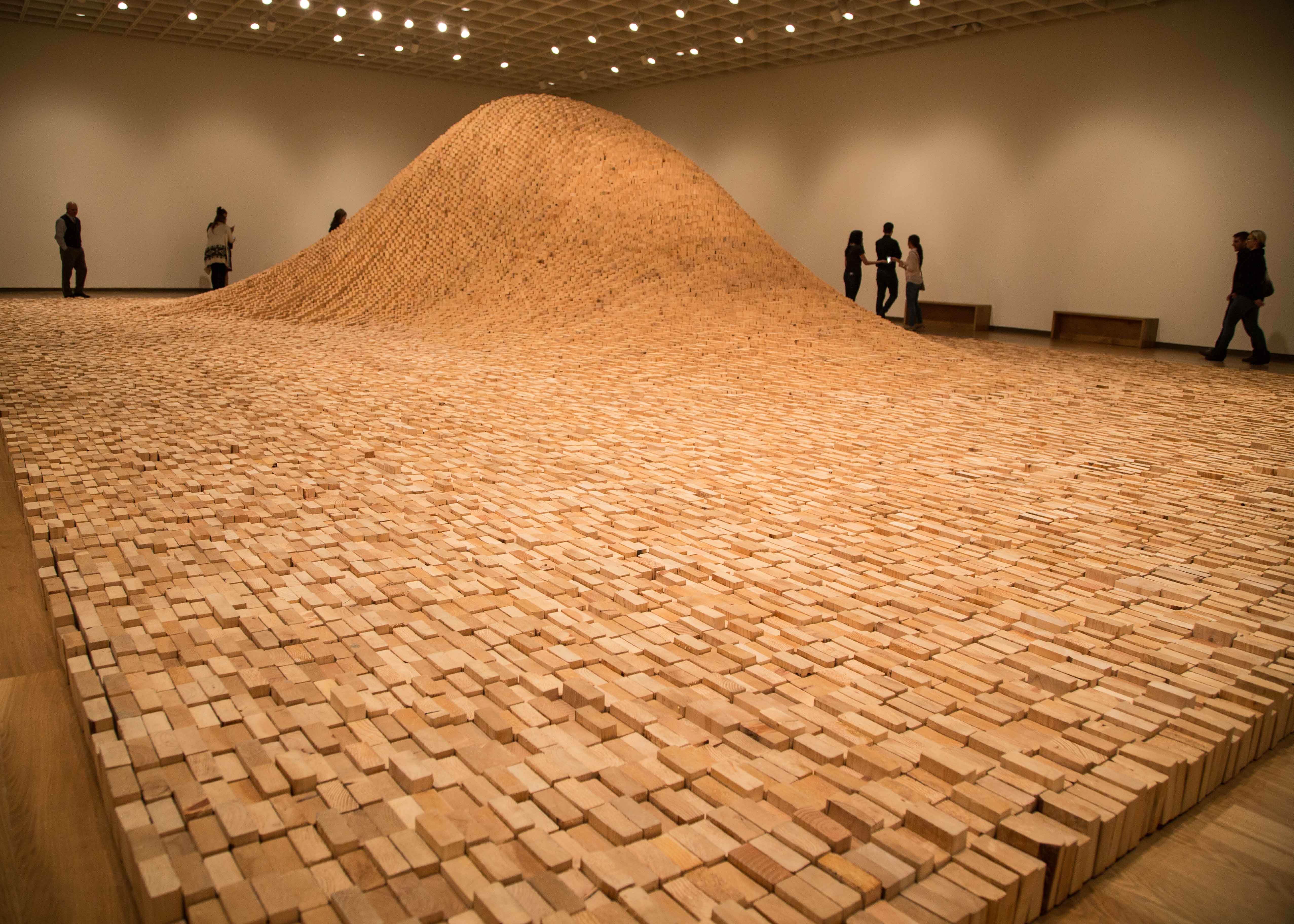

In Orlando Weekly's interview with the artist last month, Lin uttered this self-assessment, and I couldn't disagree more. While her work is certainly subtle – even, to some eyes (not mine), austere – I find it anything but quiet. The sensuous wave of her timber installations "2x4 Landscape" and "Flow," her swelling cast-silver waterways and glittering Pin Rivers, and especially the undulating solid masses of her Missing Bodies of Water – all of them thrum with a clarion message: This is what we've lost. This is what we're losing. This is what we still have to lose.

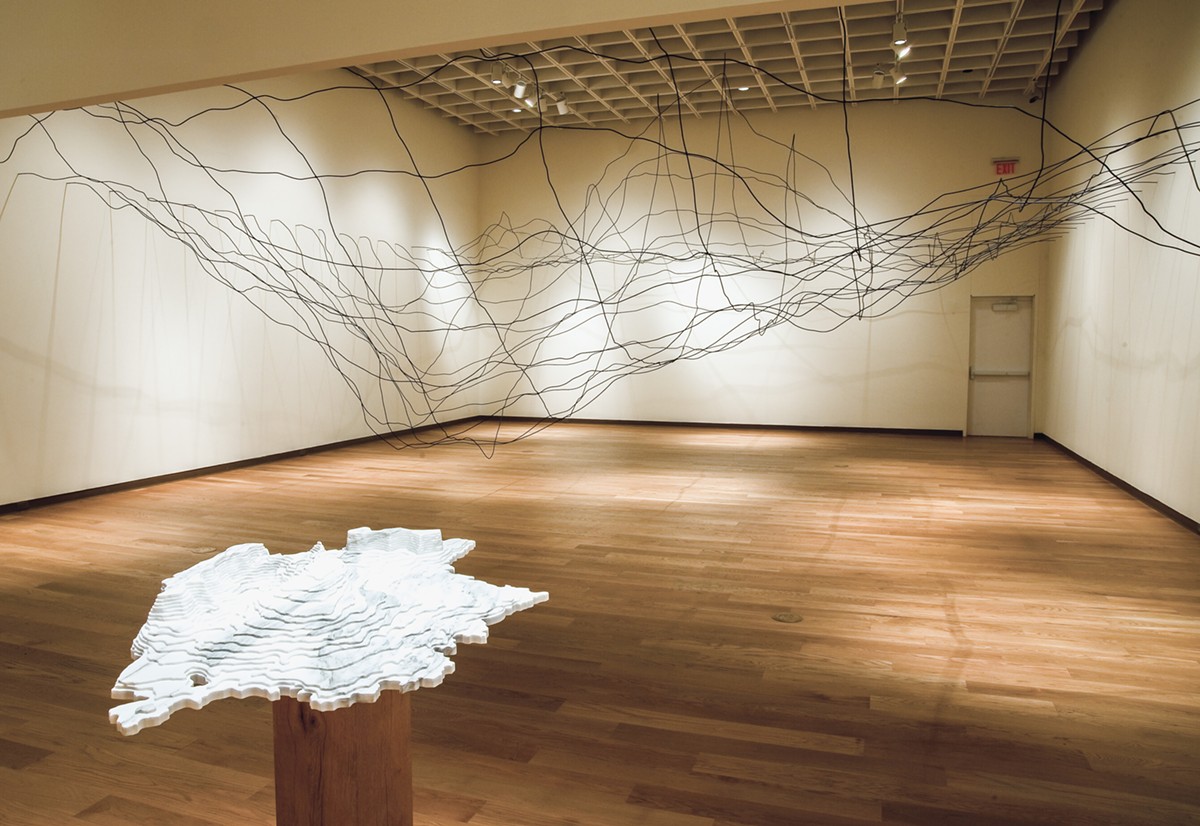

Though Lin is known for her masterful earthworks and giant-scale memorials, this show focuses on more personal, more handmade objects and installations, and on the artist's self-labeled "obsession" with water – wave forms, undersea topography, disappearing lakes and rivers. With a wide range of materiality, from lowly 2-by-4 lumber and steel pins to cast silver and carved marble, Lin creates a tactile narrative of the natural world.

"We are less inclined to pollute the things we are able to see," Lin says, and so these works solidify negative space, asking viewers to reverse their vision and consider the water, not the land, as an organic whole.

The three marble rings that make up Around the World – "Equator," "Latitude New York City" and "Arctic Circle" – are not mountain ranges, but longitudinal slices of the globe, re-creating topographical maps of the ocean floor. (So, yes, mountains – but underwater ones.) That they are set on the floor, not mounted on a pedestal, subtly reinforces their reality – this is a representation of the real world, not some gewgaw in a glass case. Lin's Disappearing Bodies of Water are just that: using painstakingly researched data, they re-apparate the Aral Sea, the Red Sea, the Caspian Sea – lakes and oceans that are drying up due to climate change – in Vermont marble and Baltic birchwood.

This series brought to mind Rachel Whiteread's House, a monumental 1993 work that cast in concrete the entire interior of a condemned terrace house in East London. Much as Whiteread's somber House used negative space to preserve and memorialize a very specific way of life, one that was being razed along with the physical building, Lin's Disappearing Bodies preserves and memorializes these specific lakes, calling attention to the erosion of natural life forms.

Regarding her newest project, What Is Missing?, Lin says it's "taking me out of my comfort zone. Because I'm advocating. ... Because I had to, because I don't think we have much time." It's not all gloom, though. "We could turn this around tomorrow. If you look at what happened with the ozone hole, and banning CFCs — that happened in, what, a three-to-five-year window. It was fast, it was done, and I think you've gotta be hopeful that we can turn this around." Lin refers to Missing as her "last memorial," and while it's true she has never explicitly called for change before, it's a natural progression – her memorials have never been neutral.

"A lot of my work is using scientific data to get you to look at the world differently," Lin says. By displaying what's hidden, she makes absence tangible. And this is the connection between What Is Missing? and A History of Water: Lin's ability to make the absent beautifully present, or rather to make absence powerfully tangible, in the hope of forcing us to see what we're losing.