Cops involved in the routine raid of Cleo's adult nightclub a few days before Christmas 2001, have probably long since forgotten the events of that Sunday evening. As is custom with such operations, the officers stormed the medium-sized club, which is decorated in Egyptian décor, and immediately took over the DJ booth. They cut the music and began giving orders to the roomful of strippers and their male clientele. Nobody was to move, talk or even take a sip from their drinks.

About half of the officers were Orange County deputies, dressed in the green-and-gold uniforms of the department. The rest wore white golf shirts, black pants and black hoods pulled over their heads. These were agents of the Metropolitan Bureau of Investigation, a special agency that prosecutes organized crime rings in the drug and vice trade. Two MBI agents had run a two-month undercover operation on Cleo's dancers in which they discovered that, in exchange for $50 tips, eight women, using stage names like Luscious, Mirage and Cinnamon, would slide their bikini bottoms to one side, exposing their anuses and vaginas.

Clubs such as Cleo's are required to provide Orange County administrators each month with the names, addresses and photo identification of all strippers who dance for them. Which means the strippers could have easily been taken into custody quietly at their homes. But that would have robbed the scene at Cleo's of drama. "The MBI likes the show," says Morris Wade, Cleo's tall, robust 48-year-old general manager. "They like to be seen."

The eight dancers under warrant were separated from the other strippers, cuffed with nylon cord and hauled down to 33rd Street jail, where they were officially charged with crimes including prostitution, straddle (or lap) dancing and violating the county's 11-year-old public-nudity ban. With the exception of Audra Yolanda Nance and Judith Jolicoeur, all the dancers pled guilty to reduced charges and were given light fines commensurate with second-degree misdemeanors. Nance opted for trial, lost and got a $453 fine, 180 days unsupervised probation and five hours community service. Jolicoeur was never arrested; the MBI still has three outstanding warrants on charges relating to the Cleo investigation.

While the officers involved in the takedown moved on to other business, the fight over the only adult nightclub in Central Florida catering to a predominantly black clientele was far from over. As an example of how county officials and MBI work together to use extreme, overreaching tactics to target the adult-entertainment industry, government attorneys have worked for two years to suspend the club's license even though no owner, manager or doorman was ever charged in connection with the 2001 investigation.

The MBI could have required Cleo owner Gerald Uranick to beef up security or rearrange the inside of the club, preventing dancers from interacting with customers in dark corners. Instead, the MBI went for the throat, trying to shut down the club for 30 days.

"Everything is taken to task," says Wade, taking a break in his office several weeks ago. As he does every night at Cleo's, Wade is dressed in a tuxedo with a whistle around his neck, which he uses to pump up the crowd. "Nothing is ever easy with these people. We'd like to police ourselves in conjunction with the MBI but the MBI doesn't want any part of it."

The MBI has a well-earned reputation for ruthlessness when it comes to driving adult businesses out of Central Florida. Its agents and prosecutors have harassed and intimidated witnesses, lied about investigations, trumped up charges against old ladies and spent hundreds of thousands of tax dollars -- as was the case in the infamous Rachel's investigation -- to coax a handful of people into committing petty crimes. No wonder the MBI is the most reviled law-enforcement agency in Central Florida. "What a waste of fucking money," says Doug Head, chair of the Orange County Democratic Party.

But this is Orlando, a fairy tale land of family friendliness where adult sexual urges are frowned upon. Consequently, Orange County has some of the most restrictive adult entertainment laws in the southeast, if not the entire country. In Dallas, Houston, Atlanta, Tampa, Miami, Ft. Lauderdale, New Orleans, Melbourne and Cocoa Beach, men can still pay topless women to wiggle in their laps for a $20 tip. In Orlando, you get bikini bottoms and nipple tape.

Using the MBI as a battering ram, the county has forced every live nude show from the area, has clamped down on small video-store operators who stock adult material (they tend to shy away from big stores that can defend themselves) and shut down more than 200 escort services. Look for an ad in the phone book for an adult men's club. You won't find it. The MBI has pressured publications, including the Orlando Sentinel, into not publishing legal ads for the sex-entertainment industry. (When a publication does print such ads, as Orlando Weekly does, MBI agents routinely show up demanding records for the people who bought them. The Weekly's policy is to cooperate, though MBI agents could learn all they need to know by calling the phone numbers in the ads themselves.)

It's true the MBI has been successful, but only by degrees. It is, after all, up against a powerful, unbeatable foe: the human sex drive. Which means you can still find oral sex off the Trail for $20. You can still find all-day female companionship for $1,200 through the Internet. And you can still exercise your First Amendment right to buy hardcore porn across the county.

But if you're looking for an effective governmental agency accountable to the people it is supposed to serve, you'll have to look beyond the MBI.

Troubled from the start

The MBI is often called a task force, but the name doesn't really fit. It is a permanent agency, an amalgamation of law-enforcement officials from Orange County, Osceola County, Orlando, Winter Park, Apopka, Ocoee, the DEA, FBI, Immigration and Naturalization Service and the U.S. Customs Service. It employs three sworn managers, 29 sworn law enforcement agents, seven civilian positions and two drug-sniffing dogs. Agents are divided into five narcotics units and one 13-member vice section.

The MBI has a budget of $2.7 million -- a number that has doubled in the last 15 years -- paid for equally by Orlando and Orange County taxpayers. (It has also collected $135,000 in forfeited assets seized from drug dealers in the last three years.) MBI headquarters are located apart from other law-enforcement agencies, on the top floors of a downtown office building (The MBI asks reporters not to publish which building they're in.) Local lore has it that MBI agents lock up drug dealers, pimps and prostitutes in a holding cage that hangs off one side of the building. The cage is there, but it is used for building maintenance; the MBI has no holding cell in its offices.

The agency was founded in December 1978, in the days when Carl Langford was still mayor of Orlando, Robert Eagan was state attorney and Melvin Colman was sheriff. Back then, streetwalkers on the Trail were known to approach cars, even those occupied by families, asking to perform sexual favors. Places like The Connection were thinly disguised brothels where you paid $45 for a room, then negotiated with a female employee for sex. Consequently, most MBI arrests from 1981 to 1987, were for prostitution (1,579), not drug arrests (968).

Two MBI officials are almost synonymous with the agency. The first is Joseph Cocchiarella, a 47-year-old Satellite Beach native who has worked for the Orange County state attorney's office since January 1981. Cocchiarella has served in a number of roles with the MBI, including as its director from 1988 to 1991, and as its legal advisor for the last decade. Cocchiarella literally wrote the book on the MBI, helping to author the "MBI Policy" and "MBI Undercover Surveillance and Techniques" manuals with two other prosecutors in 1987. Officials have heaped praise on him for helping to write adult-entertainment codes in Palm Bay, Lake Mary, Deltona, Altamonte Springs, Sanford and Osceola County.

Cocchiarella's superiors love his work: He received a merit-based, $3,500 raise three years ago, and a $2,766 "top performer" bonus in May 2001.

The other official is 57-year-old William Lutz, a former Orlando Police Department captain named MBI director in 1994. Lutz's affiliation with the MBI dates back to the inception of the agency. He was head of the MBI drug unit from 1979 to 1982 and director of the agency from 1986 to 1988.

Both Cocchiarella and Lutz were already fixtures in the MBI when reports of ethical lapses first came to light. In a series of articles written in 1987 and 1988, Orlando Sentinel reporters Jim Leusner and Bob Levenson uncovered dubious decisions made throughout the 1980s regarding agency's use of street informants.

The MBI was one of the first agencies to use what is known as the three-for-one system, which provided convicted criminals with a unique opportunity to reduce their sentences. To avoid stiff punishment, they had to help the MBI set up three other people. What sounded like a questionable policy on paper turned out to be awful in practice. For example, the MBI turned its back while a teenager named Dawn Jackson turned tricks and snorted coke as she worked to set up low-level criminals. In 1984, agents recruited two 14-year-old girls to buy lewd greeting cards from a gift shop. The MBI paid career-criminal Bob Hicks $30,000 to play the middleman in drug deals. Instead, he sold drugs on the side as agents continually bailed him out of jail. The MBI even gave him a percentage of the drugs he sold, Hicks told the Sentinel reporters. MBI agents also placed mistaken trust in "Bad Bob" Bennett, who talked his way out of a conviction for selling a pound of cocaine and 28,000 Quaaludes by turning informant. According to the Sentinel stories, the MBI never got the information they wanted out of him.

The MBI also wasn't against questionable policing techniques. Instead of arresting homosexual prostitutes having sex in a hotel room, agents videotaped them in order to break up a larger prostitution ring. But prosecutors wound up dropping the charges against the men because, as Lutz was quoted saying, the videotapes "had no jury appeal and were traumatic for agents to sit through."

In 1983, an MBI agent infiltrated a nuclear protest group whose members included teachers and religious leaders. Lawson Lamar, then Orange County sheriff, suggested the undercover operation was necessary because of the group's alleged ties to Libyan President Moammar Kadhafi. The MBI agent concluded, however, the group's chances of violence were "extremely remote."

Big or little fish?

Part of the MBI's problem, which has never been corrected, is its loosely defined mission. According to the agreement that formed it, the agency's purpose is to direct manpower at "vice, organized crime, racketeering and other criminal enterprises in Orange County, Florida."

Some early directors took that to mean fighting drug cartels and Mafia-type kingpins, as if Orlando was a fiefdom ruled by the likes of Tony Soprano. Other directors went after ordinary street crime, including streetwalkers and open-air drug sales. But Orlando and Orange County have organized their own drug units, leaving some observers wondering why the city and county still pay for the MBI.

As a result, the MBI has to continually justify itself. One way to do that is by inflating the importance of its investigations.

In the case of Cleo's, that led MBI agents to rely on sketchy testimony from Pallis May Paulk to try to get the club shut down. Paulk, a short, wiry, 21-year-old stripper, turned out to be one of the worst offenders in the Cleo's investigation. Not only was she busted for breaking the county's anti-nudity ordinance, she also sold undercover agents Cynthia Meinke and James McGriff a half-gram of cocaine wrapped in a dollar bill.

To avoid a 15-year drug-distribution sentence, Paulk turned state's evidence, snitching on other girls in the club as well as its manager, Morris Wade. "Everybody has their own little group of what they're doing in there," Paulk said in a June 2002 deposition taken by MBI prosecutor Greg Tynan. "My thing was to sell cocaine in the club. I know there was another girl in there that sold pills. I know there was another girl that sold heroin."

She said she saw Wade (whom she called Moe) in his office greeting two men who had brought $1.5 million worth of heroin into the club in a suitcase, presumably to distribute it.

Later, though, she contradicted herself by saying Wade was selfish with his drugs. "See Moe didn't let anybody too much touch his heroin," Paulk testified. "You know, that shit there was his. That crystal meth too. He didn't let anybody touch that really too much. He did that himself." Paulk also said Wade ran a prostitution ring from the club at a rate of $3,000 per hour.

"According to her, I'm a pimp, drug dealer, you name it," Wade says. "But if you're going to say something like that, make it real. Make it believable. She said what `the MBI` wanted her to say."

Paulk met with Wade in June this year. According to an affidavit signed by James Jacobsen, Cleo's director of operations who was listening outside Wade's door, Paulk told Wade she made up the stories because she was facing a 15-year sentence. She said the MBI pressured her to bring more allegations about Cleo's.

And then she disappeared. Cleo's attorneys have tried to locate her to discover which versions of events she's willing to stand by. Her testimony was going to be crucial. The MBI, in conjunction with Orange County attorneys Joel Prinsell and Linda Brehmer Lanosa, used it to try to close the club.

On Aug. 5, the county finally settled with Cleo's. The club must pay $35,000, which is a slap on the hand for owner Gerald Uranick, who owns seven other clubs. "If the business is closed," explains Cleo attorney Steve Mason, "that's a strike on your license. The next time they can close you for three to six months. You don't want one strike on your license."

Too close for comfort

The other fundamental problem with MBI is how closely prosecutors and cops work together. Not only is Lawson Lamar on the board of directors, but Cocchiarella and another assistant state attorneys work out of the MBI's offices. Consequently, the line between cop and prosecutor is blurred, with little or none of the usual checks and balances. In Colorado, for example, Eagle County District Attorney Mark Hurlbert waited two full weeks to formally charge basketball star Kobe Bryant with sexual assault because he wanted to make sure the facts police gathered warranted the felony charge. "I have an ethical burden not to prosecute a case unless I can prove it beyond a reasonable doubt," Hurlbert told Sports Illustrated.

The MBI doesn't display the same kind of restraint. Cocchiarella routinely files felony charges carrying 30-year sentences to convince witnesses to testify.

In November of last year, two days before Thanksgiving, the MBI arrested three women who sold porno tapes to its agents at Jerry's General Store. Jerry's General is a homely, mom-and-pop bookstore in Union Park. A black-and-white cat sleeps in a basket on the counter. A handmade sign reads, "Life is boring without friends and family." In a smaller room on the east side of Jerry's, separated by a cinder-block wall, customers can buy hardcore porn like "Dr. Fellatio" or "Midgets Gone Mad," and sex toys like two-sided dildos. Jerry's opened in April 1976 and never obtained an adult bookstore license. The county didn't regulate adult stores until 1977, and it is legal for stores to sell adult material as long as it does not constitute a "substantial portion" of their sales. Orange County has never defined what that means.

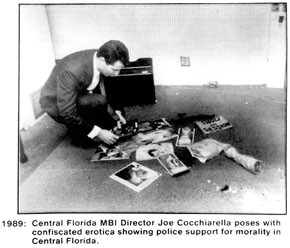

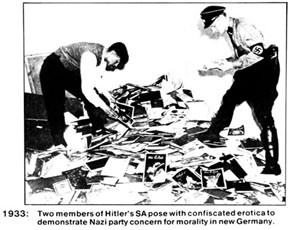

Jerry's is named for Jerry Cooper, an entrepreneur with a libertarian streak who died three years ago of unknown causes after partying on his boat in Titusville. The MBI arrested Cooper for selling adult material in 1987, but Cocchiarella dropped the charges in 1990. Cooper didn't forget, though. He produced a poster of Cocchiarella picking over pornographic material in a manner identical to Nazi morality police 50 years earlier when the fascists were trying to keep Germany pure and orderly. Cooper also put stickers on his products alerting customers to Cocchiarella's censorship, requesting they call and complain to him. When his daughter, Roxie Hanna, inherited the store, she predicted trouble.

Hanna, who was born with her father's libertarian streak, turned out to be correct. The MBI began making undercover purchases at Jerry's last summer to set up Hanna, her mother Diana Cooper, and Eileen Hart, a 75-year-old woman who has been Cooper's surrogate mother since Cooper was a child. Hart, who can't see well, is a part-time employee content to stay at home watching her favorite program, "Wheel of Fortune," and collecting Social Security. But Hanna felt it was important to get Cooper out of the house.

After purchasing magazines like "Virgin Pink" and videos like "Cocksmokers #31" last summer, MBI agents arrested the three women and charged them with distributing obscenity and racketeering, which means they profited from ongoing sales of pornography. Each woman was slapped with an enormous, $50,000 bond. (Hanna says a pedophile locked up about the same time was arraigned on a $5,000 bond.) Then, according to Hanna's attorney, Dick Wilson, the MBI went to great lengths to keep them in jail over the long Thanksgiving weekend. First MBI attorney Greg Tynan failed to tell Wilson which judge was hearing the women's bail-reduction hearing -- a common courtesy between prosecutors and defense attorneys. When Wilson finally discovered which judge would handle arraignment on the afternoon before Thanksgiving, Tynan presented the court with a seven-page memorandum of why the three women shouldn't be released. Unfortunately for the MBI, Circuit Court Judge Stan Strickland didn't agree with the bail amount, reduced it, and the three women were released at 1 a.m. Thanksgiving morning.

The entire incident left Dick Wilson fuming. "You can add up all the MBI's big wins on one hand," says the attorney, who has battled with the agency since its inception. "They are corrupt, lazy, inept stumbling bums who are using the system to get themselves nice, fat incomes."

Hitting the three women with racketeering charges is like swatting a gnat with a frying pan. Yet prosecutors defend the practice of charging small-time offenders with felonies, saying if they did the crime, they should do the time. "The laws were meant to apply to whomever falls within the language of the statutes," says G.R. Blakey, who helped write the first federal racketeering laws in the early 1970s, and is now a Notre Dame law professor. "They say 'any person.' They do not say 'any high-level person.' Some of the statutes passed around 1970 like RICO are aimed at only high-level people. There is no 'Mob-only' defense, and there is no 'not-me-I-am-a-low-level-guy' defense. If your culpability is low-level, that should show up in the sentence."

In June, the MBI quietly dropped charges against Hart, saying she had provided them with evidence involving sales-tax evasion. Wilson says the MBI dropped charges as a result of the public backlash against the agency after her story was broadcast on WKMG-TV. "The MBI was tired of seeing her on the Channel 6 news," Wilson says. "She was a huge embarrassment to them. They will tell you they dropped charges because they got information out of her. They didn't ask her a damn thing they didn't know already."

In June, the MBI filed additional charges against Hanna and her mother, saying they owe the state $3,000 in sales taxes dating back to October 2000. According to David Bruns, a spokesman for the Florida Department of Revenue, it is extremely rare for a local law-enforcement agency to prosecute on sales tax evasion charges. "They are more than pleased to leave this to us," Bruns says. Tax evasion is often a sign a business is struggling, he says, and prosecution is used as a last resort. "We are delighted to work with businesses. It's the least expensive way to proceed. We resort to prosecution after we've exhausted all other opportunities or if we have an uncooperative situation."

Of course the MBI doesn't work that way. Hanna says the whole case is about payback for Jerry Cooper's slight of Joe Cocchiarella years earlier. "This is nothing but a grudge fuck," Hanna says. "When the old man passed off the store to his daughter, they said, 'We're going to go back and fuck that bitch.' There are a lot of vindictive people out there. If you can't get the father, get the kid."

Big time flop

The agency's most publicized flop involved Rachel's, an investigation in which agents spent $193,000 to build a racketeering case against the club's owners, but ultimately managed only to coax low-level employees into breaking the strip club's rules.

The MBI's questionable calls started from their choice of lead investigator when they decided on agent Cleveland Ray Peters for the January 2000 investigation. Peters, a 26-year Orange County deputy who moved from the sheriff's vice squad to MBI in September 1995, was involved in an internal-affairs scandal just six months before the Rachel's investigation began. Patricia Howard, a former prostitute, claimed Peters had sex with her in a hotel room in 1988 several weeks before he was to be married. Sex between the two produced a son, according to Howard. Peters claimed the sex was consensual, and he didn't pay for it. Orange County internal affairs cleared Peters of misconduct charges.

There are actually three Rachel's clubs -- one in Casselberry, one south of Orlando on Orange Avenue and another in Palm Bay. They're one of the few adult clubs in Florida that are also a full-service restaurant. The MBI believed that wealthy friends of Rachel's owners Jim and Charlie Veigle -- brothers who amassed a fortune in the Tom's Pizza and Beefy King fast-food franchises -- were receiving sexual favors from Rachel's dancers in exchange for large tips. Peters and his colleagues, posing as high-rollers, tipped managers $400 to look the other way while they snuck strippers out of Rachel's for two-girl sessions in the back of a limousine. The strippers were paid $7,000 each to make out, perform cunnilingus and penetrate each other with a strap-on dildo. The sex was recorded on hidden video cameras.

The question is how far MBI agents had to push Rachel's dancers to get them to perform. Sifting through depositions from the case, it becomes apparent that the Veigles not only did not condone illicit activity, they tried to ensure it wasn't happening at their clubs.

Robert Rexroad, a Rachel's manager MBI agent Peters had to practically beg to come on one of the limousine trips, says on tape he's afraid of being caught. "I'm a little worried," he says. "I don't want to get in trouble. If the owner calls, I'm not here. A lot of shit has been going on." Delores Hurrell, a Rachel's dancer briefly famous for her large breasts prominently displayed on an Orlando Predators billboard, tells Peters not to disclose her two-girl show to general manager James Mulrenin. Later, she tells Peters that Veigle fired Mulrenin after he was caught allowing other girls to leave with one of Mulrenin's friends. The same night, when Peters badgers manager Sean Smith to allow girls to leave, Smith responds, "I have to see what's going on. The owner's been in here like every night fucking laying down bricks." When Peters suggests allowing the limousine to pick up the dancers at a nearby Denny's, Smith says, "That would be a much smarter idea. They'd have to drive out of here in their own cars to make it all legal."

At one point in the investigation, Ann Marie Stevenson, one of the strippers who performed in the limo, tells Peters that the entire dining room staff had been fired because "someone had ratted them out." She also said the rumor going around Rachel's was that Agent Peters was a "spotter" sent in by Veigle to spy on his employees.

Carlos Sanchez, a contracted limousine driver who sold Peters $2,400 worth of cocaine, was one of several people who had Peters pegged as an undercover agent. "If this is a sting operation, you fit the profile," Sanchez said. "You would be perfect. You spend a lot of money in here. It could be DEA money for all I know."

Some of the dancers in the sex shows were high on tequila shots and GHB, a liquid drug that provides a temporary euphoria similar to ecstasy. Others seemed desperate for cash. A moment after a stripper identified only as Melissa talks about her two young children's college fund and Winnie-the-Pooh collection, she tells an agent, "I'll fuck anybody, damn it. Just show me the money."

On July 20, 2000, MBI raided both Rachel's in the same fashion as the Cleo's raid later that same year. Only this time, the MBI alerted television crews, who filmed the big takedown. School buses were lined up to cart suspects to nearby elementary schools and the county courthouse for interrogation. Thirty Rachel's employees were arrested and convicted. None served prison time except Sanchez, who got three years for dealing cocaine. Despite the lack of evidence that Jim Veigle was involved in illicit dealings at his clubs, the MBI charged him with racketeering.

The MBI also showed how vindictive it can be. Several days after the raid, MBI investigators interviewed Timothy Cash, a limousine driver who was also a reserve Kissimmee police officer. During a conversation in which Cash praised Veigle for being an "outstanding person," MBI agent Michael J. Laney replied, "Tim, I don't want to offend you, but being a sworn law-enforcement officer, you sure aren't very good on detail."

Statewide prosecutor Kellie Tomeo sent Kissimmee police a memo saying Cash had been uncooperative in the MBI's investigation of Rachel's. Kissimmee later released Cash from duty for associating with felons even though no one involved in the Rachel's investigation had yet been convicted.

Agent Paul Winsett, an Orange County corporal who began working for the MBI in 1994, chastised Cash for working at a strip club. "I've been in law enforcement since 1985," said Winsett, who began his career as a Winter Park patrolman. "So I find your association with this type of business something I wouldn't even think of. When I got hired here, you weren't allowed to be seen in, on, around, near associating with any adult-entertainment oriented business. It was a disgrace to the sheriff and reason for immediate termination." Yet Winsett was videotaped rubbing the inside of a dancer's thigh and getting a kiss on the cheek. On the same tape he gushes to a fellow agent, "I'm going to end up fucking this girl. If not here, somewhere else." Winsett goes on to tell a female agent that he had an erection he didn't think would ever "go away."

In court he said his comments were taken out of context and that he was role playing. On one of the surveillance tapes, however, he said working strip clubs was "one of the benefits of the job."

Winsett and Tomeo, the prosecutor, were involved in the most ethically questionable aspect of the Rachel's case when the two surreptitiously videotaped one of the high-rollers who allegedly bought sex from a Rachel's dancer through Jim Veigle. The videotape of the Orlando businessman and his attorney, Mark Horwitz, at MBI headquarters in November 2000 surfaced when prosecutors unwittingly handed it over to Rachel's attorneys.

On it, Tomeo and Winsett turn on an audio recorder and begin asking the businessman questions. Tomeo played the role of the tough prosecutor and Winsett the sympathetic cop. After about 10 minutes, Tomeo asks to see Horwitz in the hall. The tape recorder is turned off but the video camera keeps rolling. Winsett begins speaking to the businessman. At one point, before revealing personal details of his life, the businessman asks if the tape recorder is still on. Winsett responds no. The man then tells Winsett that his wife has had a "life change" and prefers to have sex only twice a month.

Tomeo and Horwitz re-enter the room, then Horwitz leaves with the businessman. While they are gone, Tomeo and Winsett decide to talk. But instead of speaking in front of the camera, they slide to a corner of the room and whisper so they can't be heard. When the businessman and Horwitz return, Tomeo and Winsett leave for several minutes, violating the businessman's attorney-client privilege because the videotape was still running -- though the two didn't say anything to each other when left alone.

After it was revealed that the MBI resorted to what amounts to an illegal wiretap, Tomeo denied she knew the meeting was being videotaped. In depositions, Winsett and Bill Lutz contradict her, saying she was shown the equipment. Tomeo resigned in November 2001, a month after the tape surfaced. Her boss, Rich Bogle, who heads the statewide prosecutor's office, says Tomeo left the statewide prosecutor's office in good standing. "She was a conscientious, hard-working prosecutor whom we were sorry to lose," Bogle says.

Lutz, meanwhile, put the blame for the covert videotaping on Winsett, saying he was taught himself to operate the machine. "I'm `a` third party on this," Lutz testifies in deposition. Lutz didn't even bother to review the tape to determine the extent of MBI's error. Winsett, on the other hand, knew who was responsible. "We discussed this in our vice meetings," he said in a deposition. "So, that would have `included` members of the vice unit, director `Bill Lutz` and Joe Cocchiarella."

The businessman's testimony was supposed to be crucial to the case against Jim Veigle. But the man said Veigle had nothing to do with his having sex with Jennifer Lethig, one of the dancers. (Lethig earned her 15 minutes of fame when it was revealed she had fondled Agent Laney in his pickup truck several months after the Rachel's raid.) "As far as Veigle is concerned, he's not a bad character," the businessman said. "I know `Veigle's` ex-wife. She would have told me. I've been out a hundred times with her and her boyfriend."

Despite all their bumbling, the MBI still charged Veigle with racketeering and deriving proceeds from prostitution. Other government agencies jumped in. The Florida Division of Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco tried to take Rachel's liquor license. The city of Casselberry suspended the business license for two years. The Attorney General's Office seized $700,000 from the club but had to give it back because Ray Peters had done such a poor job of linking Veigle and Rachel's to illegal profits.

In mid-July, Veigle accepted a plea agreement. Two of the corporations that own Rachel's pled guilty to racketeering and must pay the government $620,000. Veigle was completely exonerated. In 2000, his clubs made more than $4 million. At that rate it will take about two months for him to earn enough money to cover the fines.

Reform, anyone?

About the time the MBI was knee-deep in the Rachel's investigation, the MBI was involved in another high-profile case against Vicky Gallas, who was charged with deriving proceeds from prostitution and racketeering. Gallas ran Valentine's escort service since 1992. The MBI filed charges against her after one of her employees, Carmen Rodriguez, was arrested on prostitution charges stemming from an encounter with MBI agent Brant Rose at the Hyatt Grand Cypress Hotel.

Gallas, 43, is one of the few MBI defendants to have taken her chances in a jury trial. Usually, defendants plea bargain to reduced charges.

One of the key witnesses against her was an alleged business partner named Robert "Rocky" Mihalek, who supposedly ran the "east coast" portion of her escort service. (Gallas sold him a Broward County escort business in 1998 for $2,000.) The MBI pressured Mihalek into statements against Gallas, but they were so unbelievable prosecutors couldn't put him on the stand during her trial. Mihalek told agents Gallas was worth $500,000. The MBI was convinced she had bags of money buried in her back yard. In fact, she was so poor she had to sell her $120,000 home to pay for an attorney. Even then, prosecutor John Craft tried to block the move because Gallas' home was being leveraged to pay for her bond.

Craft, who works in the statewide prosecutor's office, also insinuated that Gallas attorney Steve Wolverton should be removed from her case by alleging Wolverton was part of a scheme to tamper with witnesses.

Gallas was ultimately acquitted, but not before the MBI's dubious tactics were revealed. Carmen Rodriguez testified that MBI agent Rose intimidated her by camping out at her job at an apartment complex. When Gallas found out about it before trial, she tried to call Lawson Lamar, Orange County's state attorney and a member of the MBI governing board. Gallas says she was referred instead to Joe Cocchiarella, who Gallas says shouted at her for 20 minutes, telling her to get out of business or face racketeering charges. Gallas also says MBI agents followed her to a Barnes & Noble, and even called her mother to tell her Gallas was involved in organized crime.

"There was a tremendous amount of arrogance," says Wolverton, Gallas' attorney. "They kind of saw themselves as federal prosecutors. Their attitude was, 'I'm a statewide prosecutor. I have all this evidence and all these resources.' If you don't roll over then they get really nasty. They break out the heavy-handed tactics. I don't know if it's a search for justice on their part."

None of the main players on the MBI's governing board seems willing to discuss the possibility that the agency needs reform. Sheriff Kevin Beary failed to respond to interview requests. Orlando Police Chief Michael McCoy designated one of his lieutenants to answer questions. So did State Attorney Lawson Lamar. His representative, Randy Means, became incensed that the Weekly would ask such questions, which he characterized as "unprofessional," "uninformed" and based on "flawed premises."

"The Metropolitan Bureau of Investigation does not have a history of problems," Means wrote in an email to the Weekly. "Conversely, they have a long and outstanding history of law enforcement successes, to include the appropriate closing of a number of illegal houses of prostitution and successfully enforcing complex drug crimes."

MBI's critics point out the agency might be forced to change if it keeps losing cases. "They need to reassess their purpose," says attorney Steve Mason, who has battled the MBI for a decade. "They've been stuck in quicksand too often latelyÃ? They need to be more global in their thinking."

Doug Head, chair of the Orange County Democratic Party, says the MBI will not be a wedge issue during the re-election campaigns of MBI board members. "Probably because America is basically puritanical," Head says. He will work against the re-election of Sheriff Kevin Beary, a Republican. But he wants to keep Democrats Lawson Lamar and OPD chief Michael McCoy's boss, Buddy Dyer, in office as long as possible.

Changes may come as the current MBI leadership steps down. Ray Peters, the lead agent in the Rachel's case, retired in June amid speculation he was forced out in part by the botched investigation. Joe Cocchiarella and Bill Lutz, given their ages, probably aren't far behind.

Until then, don't expect an agency infused with "integrity, perseverance and investigative excellence," which taxpayers were promised 25 years ago. Instead we've got the MBI.