Through smudgy clouds of dust and smoke from burning sage, a crowd of hundreds softly chants under the watchful eyes of police.

"The people gonna rise like water, we're gonna face this crisis now," they sing at increasing volumes. "I hear the voice of my great-granddaughter, we're gonna shut this pipeline down!"

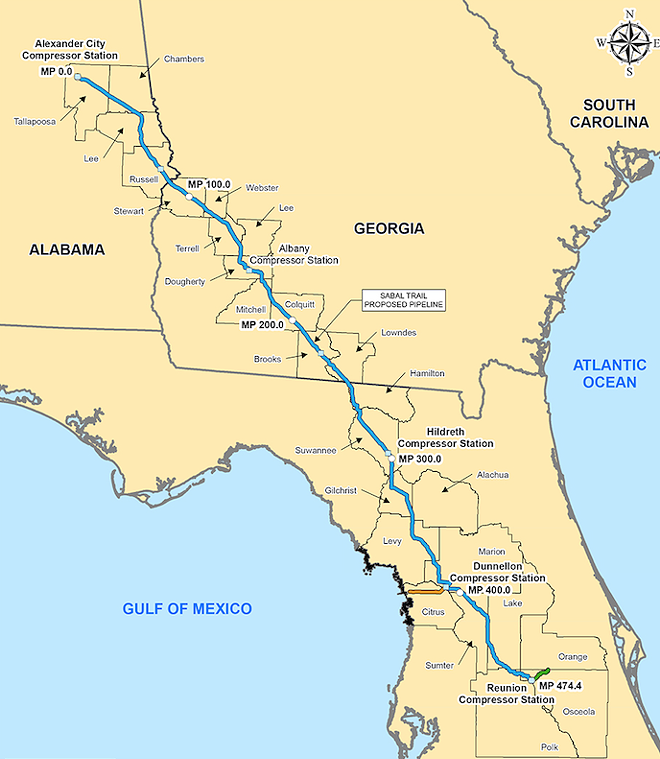

Stationed in the middle of the throng, a smaller circle of 20 people with their arms linked and locked inside PVC pipes sits on a dirt path close to the crystal-clear waters of the Suwannee River. If the energy companies get their way, beneath that same dirt will be a 36-inch pipe – a small piece of the $3.2 billion Sabal Trail pipeline snaking 515 miles through Alabama, Georgia and Florida that's meant to transport more than 1 billion cubic feet of natural gas every day from the Marcellus Shale. Plans call for the Sabal Trail pipeline to tunnel under forests, wetlands, ranches and several bodies of water, including the Withlacoochee, Suwannee and Santa Fe rivers. The pipeline will also sit above the Floridan aquifer, the primary drinking water source for people living in the upper half of Florida and southern Georgia.

Representatives from the energy companies say the pipeline will bring affordable natural gas to Florida and provide an economic stimulus in the form of increased tax revenue and local jobs. But environmental advocates and "water protectors," inspired by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's indigenous-led resistance to the Dakota Access pipeline, say Sabal Trail could potentially jeopardize the source of clean water for millions and threaten Florida's natural environment.

Because of Standing Rock, interest in the Sabal Trail pipeline has peaked, especially among young people, though the fight against the pipeline began several years ago. The crowd demonstrating in January close to the Suwannee near Live Oak was a youthful, scruffy bunch ready to be arrested for halting construction.

Toward the back, Beverly Soulshine holds her 7-month-old baby, Atom, as tears stream down her cheeks. They traveled four hours to get here from an area near Pensacola. Soulshine says she cries because she knows despite the protests, the arrests and the settlement camps, there's no stopping the Sabal Trail pipeline.

"On the day that this pipeline is built – because it's gonna be built – I want to be able to say that I was here to say I don't stand for it," she says. "They will literally cut us out to build this pipeline. I don't know why I'm here other than to say, 'I care,' and connect with people who also care."

Atom grabs onto her with his tiny fists as they look at the demonstrators.

"We're fighting for it now, but if we can't succeed, what's going to happen for the future, for the children?" Soulshine asks. "Atom is going to have to be the one to deal with it. There has to be a more sustainable way to live than to live off oil and gas. We have solar power, we have wind power, we have so much power and yet we give in to fear and money."

Soulshine isn't the only one worried about stopping the pipeline before its completion in June 2017. Environmentalists in Georgia and Florida say they've been fighting for years to get someone – the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Army Corps of Engineers, the federal Environmental Protection Agency, state departments of environmental protection, state legislators – to halt Sabal Trail and revoke its permits. Advocates hoping the increasing demonstrations would cause an intervention were disheartened after President Donald Trump superseded the Army Corps of Engineers' December decision to halt DAPL construction and revived the Keystone XL pipeline then-President Barack Obama vetoed in 2015. But other activists say they won't stop fighting until the underground pipeline is turned on, and even then, they'll be there yelling until someone turns it off.

"Florida is late to the party," Gordon Rogers says with a dry laugh.

The Flint Riverkeeper from Georgia doesn't mean to sound disparaging – it's the tone of someone who's exhausted his options in a years-long battle to stop the Sabal Trail pipeline.

"Some people protested back then, but it's not the kind of response we're seeing now," he says. "It would have been nice to have this two years ago. I'm not criticizing people for protesting now, but what's happening is just a travesty. It's absolutely ridiculous."

Rogers says almost three years ago, a group of wealthy landowners on the northwest side of Albany, Georgia, including former Florida Gov. Bob Graham and media mogul Ted Turner, reached out to the Georgia chapter of the Sierra Club and the WWALS Watershed Coalition because they'd heard about a new pipeline from Houston-based Spectra Energy that would be cutting through easements on their properties. More people joined the coalition after they realized that one of the project's compressor stations would be constructed in a predominantly African-American neighborhood. Aside from posing no material benefit to Georgia, advocates argued Spectra has had a series of troubling incidents, including $12 million in damage from an explosion at its Texas Eastern Transmission line, though the company says on its website that its incident rate is roughly half the industry average.

After the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission granted the Sabal Trail pipeline a certificate of public convenience and necessity, Spectra Energy could use the powers of eminent domain under the federal law to buy the pieces of private property it needed.

"The FERC process is completely broken from a citizen's point of view, but quite nice from the pipeline's," Rogers says. "The lawyers basically explained they were going to lose."

In a surprising bipartisan measure, the Georgia Legislature even voted down a measure to grant easements crossings under five rivers for Sabal Trail. But Rogers says that wasn't enough to halt the project.

"I hate to tell these folks in Florida, but you can't stop it," he says. "Even if the president stepped in and did something, it would eventually be overturned by the Supreme Court unless Congress changes the law. You can't win. We're trying like hell."

Aside from explosions, environmentalists like John Quarterman, the Suwannee Riverkeeper, are concerned about sinkholes that could be provoked by drilling into the karst topography filled with underground caverns and streams. Back in November, Quarterman and his group found drilling mud from the Sabal Trail pipeline leaking into Georgia's part of the Withlacoochee River. In a statement released at the time, a spokesperson for Sabal Trail said "there was never any danger to human health or safety, and no harm to the environment." The company did acknowledge the discharge was a mixture of bentonite clay and water, which Quarterman says can deplete the oxygen in the water. He's more concerned other discharges could upset the delicate system in the Floridan aquifer, ultimately affecting the drinking water.

The EPA seemed to think so as well, at least at some point. In a 30-page letter delivered to FERC in 2015, Chris Militscher of the EPA's National Environmental Policy Act Program Office wrote that the EPA has "very significant concerns" about how the Sabal Trail pipeline could threaten the Floridan aquifer and directly impact 1,255 acres of wetlands and the sensitive Green Swamp in Florida.

"The proposed pipeline is expected by the EPA to have significant impacts to karst areas in the State of Georgia and Florida and represents a potential threat to groundwater (and surface waters) resources," Militscher wrote. "The EPA is requesting that the FERC develop an alternative route to avoid impacts to the Floridan Aquifer and its sensitive and vulnerable karst terrain."

During a lawsuit brought by WWALS Watershed Coalition to stop the Florida Department of Environmental Protection from issuing Sabal Trail an environmental resources permit, the state agency joined the company in blocking the EPA report from being submitted to the court. Florida Bulldog, an online media organization, reports Gov. Rick Scott has made several investments in energy companies, including $53,000 in Spectra Energy stock in a blind trust in 2013. That same year, he signed two bills to speed up permitting for Sabal Trail, and his five appointees on the Florida Public Service Commission gave it unanimous approval to be the state's third major natural gas pipeline, according to Florida Bulldog.

Two months after the initial letter from the EPA, the federal agency reversed course in another letter, this time from the EPA's James D. Giattina to the Army Corps of Engineers. He brought the 1,255 acres impacted down to 882, with 235 acres of wetlands permanently affected.

"The EPA believes the applicants have chosen a path that avoids many of the most sensitive areas and demonstrates the karst areas in the path of the pipeline are unlikely to be significantly affected," Giattina writes.

Representatives for the project say the current natural gas pipeline infrastructure in Florida isn't enough to meet increased demands for natural gas, though Quarterman points out FPL's 10-year plan published last September says the state doesn't need a new electricity resource until 2024. Mark Woodall, legislative chair for the Georgia chapter of the Sierra Club, says he believes FPL and Duke's need for natural gas comes from their refusal to look at other energy alternatives, like solar. Last year, Florida's major utility companies were behind Amendment 1, a solar-energy ballot initiative that critics said was "deceptive" and would have limited rooftop solar expansion.

"But it's not the end until the pipe is laid," Quarterman says. "Investors could still pull out and the whole thing would fall apart. This fight isn't over yet."

Rogers says he continues to fight to "finish the drill" and hope for future FERC reform.

"It doesn't matter if you're losing because you're playing to win your reputation and to live to fight another day," he says. "The pathway to victory is exceedingly narrow, but we're not quitters. It's not over until it's over."

Spectra is taking the final steps in Florida before it turns on the pipeline this June, though environmental advocates and an Orlando eminent domain lawyer are putting up some roadblocks.

V. Nicholas Dancaescu, with the Orlando corporate firm GrayRobinson, says 41 of about 100 of his clients are still involved in eminent domain lawsuits with Sabal Trail. The pipeline crosses through 12 Florida counties, including Alachua, Hamilton, Suwannee, Gilchrist, Levy, Marion, Sumter, Citrus, Lake, Polk, Orange and Osceola counties. (In those last two, the pipeline comes down the Four Corners area close to Disney property and crosses Interstate 4 near the Reunion Resort Golf Course. Another proposed pipeline connects the compressor station near Reunion past Kissimmee and into the Hunter's Creek area.)

"In Florida, it's going through quite a few spaces that are virgin land," he says. "They've never had a pipeline. It's just a beautiful rural piece of property."

Dancaescu says most of the easements are across a section at the end of the property, but others cut across diagonally, creating three different pieces on the property. He adds that about 10 to 15 of his clients are in the "blast zone" of the pipeline, which aside from being dangerous could devalue a house.

"Our primary focus isn't stopping the project," Dancaescu says. "We want to make sure our clients are compensated fully and fairly. Some of them have been offered $1,600 for the easement, and when the time comes to sell the property, a buyer might want $75,000 to $100,000 off the home because of the pipeline."

The fight against Sabal Trail hasn't reached Central Florida like it has in some parts of North Florida, particularly Gainesville and Live Oak. Before the project even began drilling under the Santa Fe River, local springs that depend on the Floridan aquifer were already suffering from various issues, says Pam Smith, president of Our Santa Fe River. The water extraction required for agriculture, golf courses, development and drinking from the aquifer has reduced the amount of water going to the springs. The flow has also been depleted by pollution from nitrate-based fertilizers and septic tanks. Still, Smith says the small nonprofit did its best to make noise about the Sabal Trail pipeline before it began drilling under the river.

"We didn't have enough manpower to drum up support for the Santa Fe," she says. "We really had trouble getting traction until Standing Rock made people realize this was happening everywhere."

Three months ago, activists set up a camp on the property of an Our Santa Fe River member, where they've vowed to stay close to the pipeline.

"Have you ever been down the Santa Fe?" Smith asks. "It's beautiful. I'm looking at it right now. It speaks to me, and I need to help it get through this and live longer."

Back at the protest near the Suwannee River, the day is ending and police have detained no one so far, though some activists will be arrested later that week for another blockade. Organizer Panagioti Tsolkas remembers being one of the people arrested for blocking the project by the Santa Fe River. He says he's trying his best not to get arrested again because he doesn't want to miss the birth of his child.

Tsolkas says he's fought against other Florida developments before that were "done deals" and at the last minute have been reversed, so he's hopeful that can also happen with Sabal Trail.

"Demonstrations like this put the companies on notice," he says. "It creates the space for the potential to stop the project. A judge could pull the plug on the project and send them back to the drawing board based on the environmental impact statement. But in order for a judge to feel like really there's the need to do that, I think it needs to be in the spotlight. If we don't fight it at all, we don't win."