In February 2015, the Chapel Hill, North Carolina, community was shaken by the murder of three bright Muslim students: Deah Barakat, 23; his wife, Yusor Abu-Salha, 21; and her sister, Razan Abu-Salha, 19. Their neighbor, Craig Hicks, shot all three of them in the head in Barakat and Yusor's own apartment, then turned himself over to police, according to USA Today.

Thousands attended their funeral prayers. Newlyweds Barakat and Yusor had planned to attend the same dental school. Barakat was outgoing, loved playing basketball and had raised thousands of dollars to provide dental care for Syrian refugees. Yusor had spent the summer volunteering at a dental clinic for refugees in Turkey, and Razan was an artistic architecture student known for her lighthearted sense of humor.

Police arrested Hicks and said an ongoing parking dispute may have motivated the shootings, according to Chapel Hill's News & Observer, but many think the tragedy was a hate crime – Hicks often posted anti-religion sentiments on his Facebook page and made threatening visits to the victims' apartment.

It didn't happen here – but could it?

According to a December story in the New York Times, a study conducted by a research group at California State University, San Bernardino, showed that hate crimes against Muslims in the United States have tripled since the Paris terrorist attacks of November 2015. Just three months ago in Tampa, two Muslim women wearing hijabs, or headscarves, were attacked in separate incidents after leaving their mosques, and on Jan. 2, a Titusville mosque was vandalized by a man with a machete. Just last week, a man pled guilty to making threatening calls to two Pinellas County mosques in November.

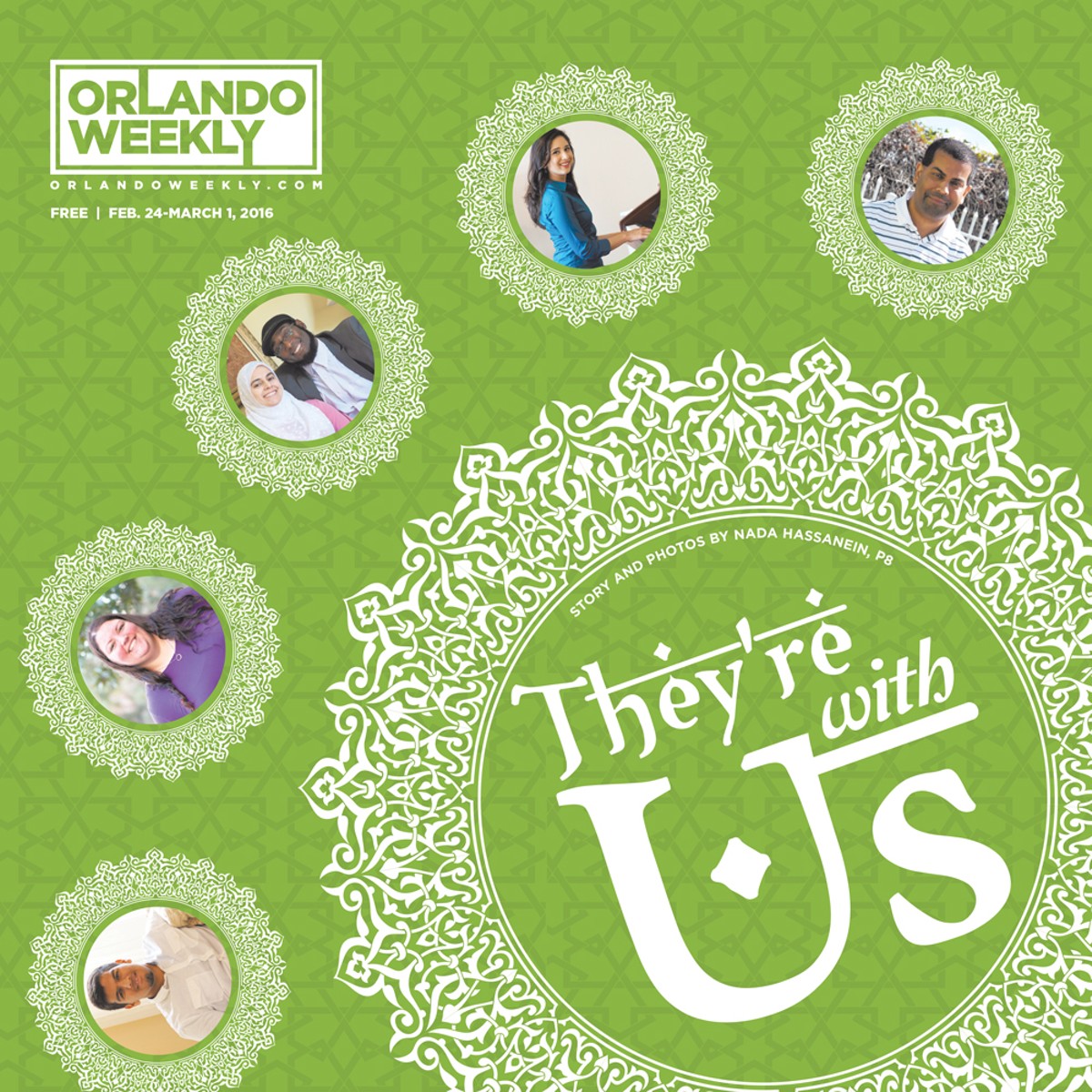

Despite the rise in anti-Muslim rhetoric and sentiment in the country, local Muslims try to live regular lives. They have personal goals. They aspire to open free health clinics. They hold neighborhood barbecues. They stay up late watching Breaking Bad. They stroll around the Lake Eola Farmers Market on Sundays. They frequent your favorite local coffee shops. Perhaps your barista, your doctor or your cashier at Target is Muslim.

In other words, they aren't all that different from anyone else.

We asked some local Muslims to tell us about their lives, how they feel when faced with anti-Muslim sentiment and how they cope with having to defend their lifestyle and religion.

Farhana Yunus and Jerry Muscadin

"Leave your religion – it's violent!"

A man yelled those words to Farhana Yunus and her daughter as they were with a Girl Scout troop touring Mount Dora. "Go back to where you came from!" he barked at them.

The caustic words brought Yunus' 10-year-old daughter to tears. With a fearful sob, she asked her mother why the man was yelling at them.

Yunus could have responded to him defensively. She could have replied, "No, Islam teaches peace" – a phrase many Muslims have at the ready to respond to similar outbursts and accusations. They mean it wholeheartedly, but it's exhausting to always be on the defense.

Instead, Yunus tried to move on, replying with a hurried "Have a nice day." But the man shot back, "I'll have a nice day when you leave."

A mother and daughter standing nearby witnessed the incident and made their way to Yunus and the girls to offer apologies. That man didn't represent their community, they told Yunus. Or us.

"They made it a point to say he didn't represent Mount Dora," Yunus says. "It was very endearing to see that, and I was thinking – would we have done the same?"

The recent political rhetoric has been hard on Muslims like Yunus and her family. Rather than shrink into the background, though, she and her husband, Jerry Muscadin, have made it a point to reach out and be more visible in their community. Last month, the Oviedo couple hosted a meet-and-greet barbecue for their neighbors. None of the neighbors seemed hesitant to enter the family's Oviedo home, whose walls are embellished with Arabic calligraphy.

The couple – he's Haitian-American, she's Pakistani – try to live their lives with mindfulness.

On her days off from her job as an optometrist, Yunus teaches Quran studies at local mosques and runs her daughter's Girl Scout troop. The mother of five spends the smidgen of leisure time she has reading – racing her husband to see who will finish the book first – or gardening. She tends fig trees, aloe vera and herbs in their white-picket-fenced yard. On the weekends, Yunus and Muscadin take the kids to the Orlando Science Center or a theme park.

"Yes, I'm Muslim, and I pray – and I go to Disney," Muscadin says with a laugh. He converted to Islam a few years before he married Yunus.

Muscadin is the director of community development for the local Islamic Circle of North America. He oversees the organization's free local clinic, food pantry and transitional housing for victims of domestic abuse. "It's a double reward in the sense that I get paid to do what I do, and I also have the opportunity to change and impact someone's life," he says, noting the time a food-pantry recipient emailed him a photo of her full kitchen pantry, which he says was empty before the Islamic Circle filled it for her.

Although the organization is an Islamic one, Muscadin says, it helps any Central Florida resident in need, regardless of religion.

As for Yunus, she says it's a beautiful thing to help people see. She remembers a time she prescribed low-vision magnification devices to an elderly woman suffering from deteriorating vision. All the woman wanted was to be able to read her Bible.

"I love the fact that I can look into people's eyes, and I see God," Yunus says.

Julianne Kinsey

It would probably never cross the mind of a passer-by that Julianne Kinsey is a Muslim. With her burnt-auburn hair and fair complexion, she just doesn't fit the stereotype most people have of what a Muslim woman looks like. The Muslim call for prayer that rings on her phone sometimes gives her away, as it did once in the middle of Vespr Craft Coffee, where she often can be found sipping a matcha latte.

Kinsey used to wear the hijab, but she says the garment that Muslim women often wear exacerbated a medical condition and sometimes caused her to faint. From time to time she misses wearing it, but Kinsey says things – even things that seem negative – happen for a reason.

"Without the hijab, people hear me," she says. "I think I'm, in a way, here to be able to help people to see Islam from a different perspective."

The lawyer, business consultant and reiki practitioner converted to Islam after a divorce that left her, a former Catholic, ridden with guilt. To reconcile her psyche – but, really, she says, to "punish" herself – she packed her things and exiled herself to Wales in the United Kingdom. After she returned, she says, she recycled some soul-searching advice she had once given to a friend: Write down everything you believe in. So she pulled out her purple Moleskine notebook and began to make a list. It included being kind, leaving things better than how you found them, being your genuine self. A friend encouraged her to read the Quran, so she downloaded an app on her phone and read it from start to finish that night, keeping her list at the ready. Everything seemed to align – the book contained all she had already believed in.

"To me, Islam is like real feminism," she says. "And it cracks me up when these feminists put down Islam." She reads different Quranic translations to dispel common misconceptions and studies the rights written specifically for women into the Quran – for instance, the right to marry and divorce based on choice and the right to pursue an education.

"I miss the hijab, the headscarf, a lot," she says. "I'm happy in that it does give me the opportunity to reach people I maybe couldn't reach with it."

Then she adds, "Alhamdulillah." That is, praise and thanks be to God.

Feryal Qudourah

If you ask what music styles Feryal Qudourah is drawn to, she will likely tell you, "All of them." She's dazzled by both somber melodies composed of Goethe's poetic verses and staccato, merry French compositions. "To sing through that poetry is to realize that there were many others before who were feeling the same as you," Qudourah says. She leans in when she speaks, and even when she isn't singing, her voice is powerful. Singing is her therapy, she says, the way she relates to the world and the way she practices empathy.

Qudourah was born to a Trinidadian mother and a Palestinian father. As a child she was intrigued by both the Arabic tunes her father and relatives in Jordan sang, and her grandmother's Urdu folk qasidas, or ancient odes. Like Kinsey, upon meeting her, many are surprised to learn she's Muslim. "Really? I would have never thought!" is the typical response she says she receives.

Growing up, her family moved often, she says, and Qudourah ended up attending 17 different schools. Hindus, Muslims and Christians lived alongside one another in Trinidad. Qudourah remembers lighting candles around her school for Diwali, the Hindu light festival, and listening to Catholic hymns and Muslim prayer calls on public radio.

Today, she's an adjunct music professor at Valencia College, as well as a private voice teacher and opera performer. Qudourah can sing in Czech, Arabic, Portuguese and other languages, so it comes as no surprise to learn that she loves to read about ethnomusicology – the study of music in its cultural context. Music can help build bridges, and she likes to use it to help people of different religions and cultures understand one another.

For instance, as the choral conductor of Valencia Singers, she has planned an April 14 concert titled "Spring In to Love From Around the World." It will feature musical expressions of love from different cultures.

"It's so much more fun to open your mind to things you're not comfortable with," Qudourah says, and she thinks music is the perfect medium to help people connect without fear. "It's a whole other dimension you've transported your audience to. You don't have to speak the same language."

Bibi Rabia Ali

It was 20 years ago that Bibi Rabia Ali walked into the TruGreen office where she worked clad in a blue hijab. It was Halloween, and everyone was dressed in costume that day. Her co-workers thought her hijab was a costume too, until she returned the next day wearing it again. Her relatives had told her to be careful, that she didn't have to put her faith out on the table. But she didn't stop. She says she loves wearing it.

"Nobody treated me any different," Ali says, remembering only genuine curiosity from her co-workers.

Ali moved to Orlando from Guyana nearly 30 years ago with just a few suitcases full of clothes and her then-2-year-old son. Back then, she says, there were hardly any mosques in the area, and she was a single mom. Somehow she landed a full-time job within five days of her arrival, and she also worked part-time as a baby-sitter. Within three years, Ali says, she bought her own house – the same one she lives in today, off Semoran Boulevard in Casselberry.

It was a lonesome beginning for her, until friendships with neighbors blossomed. Reserved and soft-spoken, with "a shell that's hard to crack," her way of unwinding is a quiet stroll on a lakefront, or visiting the local farmers market with a friend. Ali lets few in, but the ones she does are there to stay, like her neighbor and close friend who asks Ali to help decorate her Christmas tree every year.

"We're good working people," Ali says of local Muslims. "We're no different than anyone else. ... We have the same needs and the same aspirations as any other human being from any other religion."

And like people from any other religion, Ali says her life didn't quite turn out the way she thought it would. She found that, like many other Americans, she had to learn to adjust. "As a young girl, I imagined I would be married, I would have had a husband to take care of me and my life would be beautiful," she says. "But none of that happened, but that didn't stop me from living and enjoying my life. I reinvented myself. I'm happy with me."

Sameer Jagani

It was raining, humid and 18 degrees below zero on the coast of Lesbos, Greece, but Sameer Jagani made his way into the water waist-deep. He could see Turkey in the distance on the other side of the Aegean Sea. The next migrant boat had just arrived, and Jagani and the other volunteers swarmed toward it. They brought blankets to comfort the cold, soaked refugees as they helped them off the boat. Though it's just a five-mile journey from one coast to the other, the waves are merciless.

"Someone hands you a child, and for a moment, that child is yours," Jagani says, remembering the first refugee child he held – a brown-eyed 3-year-old Syrian girl. She smiled wide and greeted him in Arabic. He held her until her father got off the flimsy boat and thanked him.

The United Nations Refugee Agency estimates that more than 100,000 refugees arrived in Greece in December 2015 alone. Over this past winter, Jagani volunteered with a relief organization to aid the refugees who are fleeing not just Syria, but also Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq.

He says it wasn't enough for him to just listen to refugees' individual stories while volunteering. It made him feel heavy knowing the organization could not solve many of their problems, so he collected as many heartbreaking tales as he could and shared them on social media. There was the story of the family taken captive who needed to raise $14,000 ransom if they wanted to be released. There was the one about the father who had been tortured by the Syrian intelligence agency and had almost nothing to pay for a trip to Athens to seek asylum. He shared their stories and video blogs on Facebook, created a PayPal account and urged people to donate to help them. During his time working as a volunteer, Jagani collected more than $35,000 to help those families.

Jagani, a health sciences major and a senior at University of Central Florida, hopes to become a doctor or physician's assistant, and he hopes to practice medicine in developing countries after he graduates.

He finds the news about state governments that wish to reject refugees and deny the most desperate people help disheartening.

"We don't need to send them to a camp and leave them stranded," Jagani says. "They'll actually make our country better."

Muhammad Adam

For the past seven years, Muhammad Adam has spent his Sunday mornings spearheading the local Project Downtown homeless feeding. He's rounded up volunteers to pack and distribute breakfast and hygiene packets to the homeless in downtown Orlando. People from local mosques, churches and schools gather every month to pack and decorate the bags with cheery messages and doodles.

Adam typically spends 12 hours per week planning, budgeting, fundraising and reaching out to potential volunteers, putting his skills as a manager for a commercial-lighting company to work to organize the effort. He says it's his goal to do something small but consistent to give back to the community.

Adam has been married for the past 10 years to his wife, Michelle, who is not a Muslim. And despite how he spends his free time and the fact that he's married to a Christian woman, he says that many people see only his first name and instantly have doubts about him.

"I've been asked straight up if I'm a terrorist," Adam says. Once, he says, a client asked him that very question – are you a terrorist? – and Adam responded simply by asking the client to give him a chance. Even though it can be frustrating to have to prove himself, sometimes those ignorant questions can mark the beginning of understanding.

"Let me shake your hand, buy you a cup of coffee," Adam says. "I always open the floor and say, even if you want to vent, I'll listen to you."

Nada Hassanein is a journalist based in Orlando. She has a bachelor's degree in journalism and psychology from the University of Central Florida. Contact her at [email protected] or follow @nhassanein_ on Twitter.