Feeling overwhelmed by the vast cornucopia of independent features and documentaries on offer at the 15th annual Florida Film Festival? You won't be after you devour the in-depth reviews on the following page. To plan your moviegoing to the split-second, see the full event schedule. And check back next issue for critical highlights of the festival's closing weekend.

212

Directed by Anthony Ng

9:30 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal Winter Park Village Stadium 20

4 p.m. Friday, March 31, at Enzian Theater

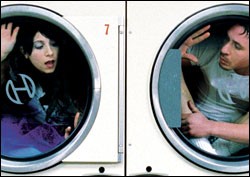

New York, N.Y. – land of cramped apartments, cramped lives, loneliness and alienation, all set in the midst of 16 million fellow humans. In this quiet, quirky comedy, three sets of people seek love, with varying degrees of success. Their lives just barely intersect, giving a believable coherence to what otherwise would be cinematic contrivance.

Seth (Brian Gant) meets Viv (Catherine Zambri) in a laundromat. His laundry compulsions give Viv an opening, but a missed date sets them back months. Ama (Michelle Luchese) systematically destroys her workplace in pursuit of handyman Antonio (Johnny Sanchez) while she learns enough Spanish to make out with him. Vincent (Ajay Naidu) gets the ambiguous relation: His live-in girlfriend blatantly cheats while he obsesses on Ama, who he saw in a forgotten photo. Too bad for Vince that Antonio got there first.

Shot in a clear, calm manner around Greenwich Village, Ng's film (based on his 2001 FFF short, "dot dot dot") is driven by style and camerawork, rather than by tension or action. Long stretches of silence are filled with a gentle soundtrack. You sort of want all these people to end up with someone nice, but it's never as important to the watcher as it is to the watched. This is a good chill-out film for the festival viewer who's seen too many earth-shattering films by angry auteurs.

— Al Pergande

24/7

Directed by Mary A.C. Fallon and Daniel Priest

11 a.m. Sunday, March 26, at Enzian

The University of Florida's Documentary Institute furthers its rep for indigenous "issue" films with 24/7, a half-hour visit with two Sunshine State families struggling to provide for the severely disabled. Longwood's Holls have their hands full with daughter Megan, who is 18 but has the behavioral capacity of a 12-month-old; up in Gainesville, the parents of middle-aged Stuart Kessler can barely afford the in-home care that seems to calm their autistic son's chronically violent tendencies.

Both families, the movie argues, have been victimized by the unacceptable state of Florida's Medicaid waiver system, which is reducing Stuart's coverage and has never provided for Megan's care. (The Holls are particularly frank about the strain their responsibilities have put them under.) There's no relief on the horizon, and so the film is constructed to make the viewer want to stand up the minute it's over and march off to Tallahassee to demand redress. In that sense, the doc's brevity is in its favor: It scores its hits and gets out, leaving no room for the delusion that having watched it was involvement enough.

— Steve Schneider

Beyond Conception: Men Having Babies

Directed by Johnny Symons

7:30 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal

1:30 p.m. Thursday, March 30, at Enzian

The soap-operatic quality of a real-life story juices up Symons' (Daddy & Papa, FFF 2002) documentary, which captures an unthinkable scenario of alternative parenting: Two gay men who already adopted a baby girl want another child. Living in San Francisco (of course!), they decide to go the surrogate route this time, and contract with a lesbian who is willing to be implanted with eggs from a donor fertilized by both men's sperm (so they'll never know which one is the "real" father).

The lesbian surrogate has two children from her previous marriage and wants to relive the birth experience. She is partnered with another lesbian, who, in a separate undertaking, is trying to become pregnant using donor sperm. If all goes well, both women will be pregnant at the same time – one baby will go home with the men and the other will be a keeper.

Symons follows the story from start to finish, from an awkward meeting to an unconventional birth-room denouement. To his film's strength, he doesn't edit out the painful realities. The costs the men pay for the baby exceed the quoted $89,000; next time, they say, they'll adopt. The birth mother says she underestimated the emotional and physical drain, and it's obvious she doesn't want to give up the baby.

Ultimately, we see what happened when a couple of gay men and a couple of gay women came together for the ultimate intimacy – making a baby – when there was, sadly, no bond between them.

— Lindy T. Shepherd

B.I.K.E.

Directed by Jacob Septimus and Anthony Howard

5 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal

9:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 28, at Enzian

B.I.K.E. is that rare picture that should appeal to fans of extreme-sports docs and political invective alike. The film documents the leftist counterculture of Black Label, a national hard-core bike collective built on an anti-establishment ethos. The members face off against rival Ÿber-cycling groups in intense bike-jousting wars, a gladiatorial throwback that also acts as Black Label's initiation routine.

We see the bikers extract scrap metal to build their unique "tall bikes," get their (mostly vegan-approved) food from restaurant dumpsters and hold mass anti-automobile protests on the busy streets of New York. These scenes, so illuminating of an underground society, are interesting, but the movie really finds its calling when turning the camera on Tony Howard, a loose-cannon artist/filmmaker who has been attempting to join Black Label for a year and a half.

Knowing that the film was co-directed by Howard makes its warts-and-all depiction of the fiery antihero that much more admirable. We see him burst into tears on numerous occasions (as when his girlfriend of seven years leaves him for a Brit she met in rehab), and we witness his unfortunate descent into drug addiction and subsequent ascent toward self-actualization by forming his own rival bike gang to confront the group that so often rejected him.

At first, B.I.K.E. seems to be about people who are nothing like us, but it's these moments of relatable sincerity that make the film far more than a dissection of a movement. Its central conflict between individual need and group comfort is something we can all understand.

— John Thomason

Black Sun

Directed by Gary Tarn

9 p.m. Monday, March 27, at Regal

3 p.m. Sunday, April 2, at Regal

A matter-of-fact lesson in the destructive properties of paint thinner is a haunting highlight of Black Sun, a harrowing, impressionistic documentary that gets under your skin early and stays there. Water doesn't wash away thinner, as New York painter/filmmaker Hugues de Montalembert learned when a thief threw some of the stuff in his eyes during an aborted robbery. De Montalembert's sight began to atrophy immediately; within a day, it was completely gone.

At a stroke, he had been plunged into a world of perpetual disorientation and strange associations. His brain responded to the lack of visual input by forcing hallucinations into his mind's eye – hallucinations that were quite vivid and sometimes inappropriately erotic. Filmmaker Tarn suggests that inner magic-lantern show in a way that wisely avoids strict representation: As De Montalembert talks us through his experiences, the frame is filled with loosely related exterior shots of New York City – and the Far East, where the fiercely independent attack victim ultimately took himself to satisfy a spiritual compulsion that may have made sense only to him.

The deliberate segregation of picture and audio never reaches complete dissonance, occasionally becoming concrete enough to accommodate a simple schematic of a typical city block as de Montalembert recounts the slow recovery of his navigational abilities. (Think the idea of the blind man with hyperdeveloped compensatory senses is a cliché? Not the way this film tells it.) Yet at all times, our grasp of what we're seeing remains heartbreakingly tenuous. On several occasions, images go slowly out of focus, recalling de Montalembert's tragic loss and reminding us how fragile sight is. Black Sun achieves its own vision by showing that ours is a gift to cherish.

— Steve Schneider

Chalk

Directed by Mike Akel

4 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal

4:15 p.m. Wednesday, March 29, at Enzian

One can easily be forgiven for mistaking Chalk – an offbeat narrative feature about the agonies of teaching high school – for the real thing. At the beginning of the film, director Akel's cinéma vérité camera catches (apparently) spontaneous action and unscripted dialogue that anyone who has ever been in a modern classroom will recognize as spot-on.

But after some minutes, it becomes clear that Akel and his canny ensemble are – like the student trying to create an excuse his teacher hasn't heard yet – making it all up! In this wry and affectionate send-up of the teaching profession, the instructors at the center of the action are actually very competent actors, improvising their way through a typical year at the fictional Harrison High, all the while utilizing real students and educators as their comic foils.

Chalk is a delightfully funny movie in the spirit of mockumentaries like This Is Spinal Tap, Waiting for Guffman and Best in Show. The characters are odd and neurotic, but genuinely sympathetic and recognizable. There is the misguided young software engineer who decided to teach history because a personality test revealed that he would make a good teacher – or veterinarian; the socially inept gym coach who nit-picks her colleagues endlessly about unenforceable school rules; the egocentric social studies teacher who sucks up to the entire school community as he angles for Teacher of the Year; and the exhausted new assistant principal, who, after only five years in the classroom, gets promoted way above her abilities to deal with the endless crises on her watch.

The film will be especially appreciated by teachers and ex-teachers (of whom I am one), as it reinforces the notion that trying to pound knowledge into recalcitrant adolescent heads was, is, and always will be a bizarre adventure.

— Al Krulick

Conventioneers

Directed by Mora Stephens

4:45 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

9:15 p.m. Thursday, March 30, at Regal

The Republican National Convention is a strange place to find love – xenophobia, maybe, or free-floating hostility toward the rudely underprivileged. Yet it's amour that befalls old college pals Dave Massey (Matthew Mabe) and Lea Jones (Woodwyn Koons) as the GOP commandeers Madison Square Garden in 2004, giving the coincidentally reunited classmates a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to screw like bunnies in a nearby hotel room.

The term "conflicting agendas" was made for this pair: He's a Texas delegate determined to ensure Dubya's second (OK, first) victory at the polls, while she's an anti-war protester who intends to help carry symbolic coffins to the convention site. (They're also heavily involved with other people, which adds a layer of guilt Carville and Matalin never had to weather.) True to form, both of these party extremists are socially unsophisticated and prone to engaging in simplistic diatribes – whenever the principle of attracting opposites isn't prodding them to hammer each other's brains out. You rule out caring about either of them pretty early on, figuring that the point is to watch them rip each other to shreds emotionally.

The movie gets around to that, albeit at a pace that makes Bill Clinton's notoriously windy speech at the 1988 Democratic Convention feel like a sprint. Director/co-writer Stephens shot Conventioneers in the midst of the GOP's actual 2004 conclave, getting herself and her crew arrested (and eventually winning an Independent Spirit Award for low-budget filmmaking). Though the real-life footage is cleverly integrated into the drama, it's also belabored: The visual image of a bunch of slowly trudged coffins makes a cruelly apt metaphor for a movie that comes to a dead standstill just when it should be springing to life.

— Steve Schneider

Dare Not Walk Alone

Directed by Jeremy Dean

11 a.m. Sunday, March 26, at Enzian

St. Augustine, Fla., is known as America's oldest city. To Martin Luther King Jr. and the other leaders of the civil-rights movement of the 1960s, it was also known as one of the most racist. So it was there, during the summers of 1963 and 1964, that the Southern Christian Leadership Conference staged a series of nonviolent direct actions, marches and demonstrations, pitting a brave fellowship of young black men and women – and their white supporters – against the hostility and hatred of a community steeped in a tradition of bigotry.

In Dare Not Walk Alone, documentarian Dean has assembled archival and home footage of that time (not too distant) when American blacks were attacked, beaten and arrested for daring to ask for equal accommodation in hotels, restaurants, beaches and other public places. Though the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which smacked down the doctrine of "separate but equal," was already 10 years old, it took another decade of struggle and sacrifice for Lyndon Johnson to sign the 1964 Civil Rights Act, finally making racial equality the law of the land.

For those who remember those troubled times, there are few more salient images than that of enraged St. Augustine motel owner James Brock pouring acid into his swimming pool to chase away the black teenagers who had dared submerge themselves in its segregated waters. St. Augustine was also the place where future congressman, mayor of Atlanta and Ambassador to the United Nations Andrew Young was fiercely beaten by racist whites while police looked on.

Not content to reconstruct history, Dean's powerful film also segues into the present, revealing a modern St. Augustine in which the more subtle crimes of economic racism still bear down upon its minority community. This is an important film, though not one that will make the tourist industry very happy.

— Al Krulick

Duck Season (Temporada de patos)

Directed by Fernando Eimbcke

8 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal

That's not Duck Season in the "rabbit season, fire!" context, unfortunately – though a good Looney Tunes short would liven up some of the least eventful patches in director Eimbcke's intentionally comatose, black-and-white capture of Mexico City apartment dwellers left to their own devices by recurring power failures. Fourteen-year-old chums Moko (Diego Cataña) and Flama (Daniel Miranda) plan a day of intense video gaming fueled by sugary soda intake, only to get cut off in mid-goal. Within a short time, their couch-bound inertia is joined by a pizza deliveryman (who sticks around because they refuse to pay him) and a slightly older girl who wants to use their kitchen to bake a cake.

Director/co-writer Eimbcke's main joke is that, the minute the AC winks out, these high-rise castaways can find little to say to each other: There are numerous long, silent shots of characters simply staring into space and waiting for life to resume. Yet even in the throes of boredom, they're in the process of becoming the adults they're going to be. Despite its surface similarities to the Japanese lost-children lament Nobody Knows, the movie heads in a direction that's more Y tu mamá también, with the introduction of a female uncovering hidden truths about the masculine dynamic. There are several moments of high, unheralded humor – although whenever you find yourself laughing, you have to ask yourself if you aren't merely grateful that anything is happening at all.

— Steve Schneider

Friends With Money

Directed by Nicole Holofcener

7:30 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

Nicole Holofcener is one of those American independents who, like Whit Stillman and Jill Sprecher, make literate, unassuming festival favorites every few years before dropping off the map. But with her great human comedies Walking and Talking and Lovely & Amazing, she has emerged as an auteur of movies that illuminate contemporary relationship quagmires from the woman's point of view.

Friends With Money, if not as arresting as Lovely & Amazing, is her most mature work to date. It concerns four friends (Catherine Keener, Jennifer Aniston, Frances McDormand and Joan Cusack) of varied social and economic backgrounds struggling to maintain synergy with the men in their lives and dispel their guilty consciences. Aniston is a pot-smoking cleaning lady, McDormand an anxiety-ridden clothing designer, Keener an upper-middle-class wannabe writer and Cusack a wealthy housewife.

As the title indicates, Friends With Money is about class and the divisive effect of money. But even more, it's a film about gossip-mongering: Notice how these women never want to talk about their own problems, and how quickly the elliptical conversations with their other halves wind back to self-aggrandizing chatter about their friends' ineptitude or inequities. It's casual cruelty as a defense mechanism.

Occasionally, Holofcener succumbs to repetition: The unlikely relationship between Aniston's character and a greasy client mirrors the one between Keener and Kevin Corrigan's video-store clerk in Walking and Talking, and structurally the film has a lot in common with last year's FFF entry Duane Incarnate (sans the dopey fantasy element). At first glance, you may feel you've seen this one before, but serious afterthought reveals layers of depth and meaning, anchored by a stringent critique of both sexes.

— John Thomason

The Giant Buddhas

Directed by Christian Frei

6:45 p.m. Friday, March 31, at Regal

1 p.m. Sunday, April 2, at Regal

Deceptively tagged as "a film about the destruction of the famous Buddha statues in Afghanistan," this new documentary by filmmaker Frei (War Photographer) is so very much more. Using footage shot in China and, of course, Bamiyan, Afghanistan, Frei beautifully tells the 1,500-year history of the two enormous, cave-carved Buddhas; the spiritual impetus for the original stories-high carvings is explained and contrasted with the petulant, vengeful actions of the Taliban who destroyed them.

Through interviews with the Al-Jazeera reporter who was able to capture the destruction on film and with a Hazaran villager who lived in the Bamiyan caves, Frei posits that the Taliban wasn't seeking religious purity by demolishing the Buddhas, but simply making a desperate attempt to get the attention of a world that had abandoned the Taliban after their usefulness against the Soviets had expired. (It's hardly a coincidence that the statues were destroyed mere months before Sept. 11.) But Frei doesn't let The Giant Buddhas become a requiem for a lost artifact nor a simple condemnation of their destruction. He explores notions of cultural heritage, commodified and kitsched-up religion, brutal intolerance, disorienting progress and, frankly, just how much the West doesn't understand about either Central Asia or Islam. With principals hailing from China, Toronto, France and the caves of Afghanistan, Frei deftly tells a rich and complex story in a way that's engaging and sad without being maudlin or overly sentimental. For a film that's "just" about a couple of statues being blown up, it sure does leave the viewer with a lot to think about.

— Jason Ferguson

Hand of God

Directed by Joe Cultrera

12:30 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

4 p.m. Wednesday, March 29, at Regal

Part of the movement toward disturbing family-history documentaries – like Capturing the Friedmans, Tarnation and Awful Normal (FFF 2004) – Hand of God chronicles the story of Paul Cultrera, who in the early 1990s began to speak out about a Catholic priest who had sexually molested him numerous times 30 years earlier. His brother Joe directed the movie, capturing Paul's surprisingly calm recollections of the early abuse and his crusade to publicize the church's gross negligence in keeping the pedophile on various payrolls (despite a myriad of prior molestations).

The chilling impact of Joe Cultrera's emotionally and physically draining polemic elevates it beyond a mere movie until it becomes, like the films mentioned above, an experience for the audience to partake in. Provocations and revelations abound as the film evolves from a portrait of a victim into a confrontational dialogue on church hypocrisy and necessity.

You get the feeling Joe was finding himself as a filmmaker at the same pace that Paul was finding himself as a misconduct-exposing activist: The second half of the film is so flawlessly composed that it's easy to forget the blemishes in the first act – the murky, incessant cutaways to overdramatic close-ups of cobweb-covered religious symbols and a tarnished photograph of the pedophilic priest. These diversions, meant to add tension, only distract from an inherently compelling tale that needs no stylized accompaniment.

These sequences, in which Joe tries to be Errol Morris, may fail, but when he simply becomes Joe Cultrera, his film is the most moving documentary since Grizzly Man.

— John Thomason

The House of Sand

Directed by Andrucha Waddington

5 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

How rare it is these days to see such a luminous epic untouched by the horrors of computer-generated backdrops or set elements – especially when there's only a single location in the entire film. Waddington's grand new film brilliantly adheres to some old-school filmmaking techniques.

The story begins in 1910, following a group of settlers into the middle of a Brazilian desert. The head of the group, the abusive Vasco, brings with him Aurea, his pregnant wife (Fernanda Torres), and her mother, Maria (Fernanda Montenegro), to start his new family in a fresh landscape. The women watch helplessly as Vasco begins to construct a home for them, only to die shortly before it's completed. The workers sneak off in the night, leaving the women to fend for themselves in a house surrounded by dunes that constantly change shape with wind and time, causing their only shelter to be enveloped slowly by the sand.

Unable to find a way out, Maria and Aurea learn to adapt to their new lifestyle. Years pass, and the older Aurea (now played by Montenegro) struggles with her licentious daughter, Maria (played by Torres). The two lead actresses display a stunning ability to separate themselves from each role – and that's exactly the sort of simple technique that prevents this involving character study from becoming everything the desert offers: a dry, barren wasteland.

— Michael Ferraro

In Memory of My Father

Directed by Christopher Jaymes

7 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

1 p.m. Friday, March 31, at Enzian

Any comedy-drama that numbers Jeremy Sisto (Six Feet Under) and the great Judy Greer (Adaptation, Arrested Development) among its participants just has to be a hoot, right? You can feel the assumption slipping away early into In Memory of My Father, a largely tiresome group testimonial that won't win any new converts to the cause of indie experimentation, though it may cement your aversion to movies in which all the lead characters have the same first names as the actors playing them. (I particularly enjoyed Monet Mazur's challenging turn as, er, "Monet.")

Surfeited with underdeveloped personalities and blind-alley plotlines, the movie places three brothers at the deathbed of their father, a former Hollywood producer. The old man is colder than a halibut by the first scene, affording some highly unpleasant full-frontal nudity and much frantic activity on the part of the boys, who had agreed to document his passing on video. That means lots of handheld digital camerawork, a motif that carries over into the ensuing flood of friends and family members who arrive to pay their respects – and dredge up grievances both old and new. It's like The Anniversary Party with a noticeably dimmer view of human nature.

Though director/performer Jaymes is credited with having banged out an actual script, the movie sometimes feels like a mass improv exercise undertaken by industry pals enticed by the prospect of a convivial working weekend. (Sisto's prolonged impression of Ecstasy use is a particular waste of ability.) The dramatic passages coexist awkwardly with the gags, about one in three of which connect; divining which third is funny is entirely up to the beholder. It ain't that sad old corpse's dong, that's for sure.

— Steve Schneider

Inside

Directed by Jeff Mahler

9:15 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

6 p.m. Thursday, March 30, at Regal

Compulsion is a cruel and unpredictable mistress. Just ask Alex (Nick D'Agosto), who has been a spectator in his own life ever since his parents died under mysterious circumstances. His lowly library job allows him to indulge the peeping-Tom lifestyle he's substituted for healthy human interaction; the closest thing to intimacy he now enjoys is his embryonic courtship with a hot but obnoxious kleptomaniac (Leighton Meester of TV's Surface).

Even that tentative pursuit gets put on a back burner when Alex decides to spy on a married couple (Cheryl White, Kevin Kilner) he's spotted around the library. Turns out they've been driven around the bend by their own unspeakable grief, which becomes frightfully apparent to Alex after he suffers a pair of debilitating leg injuries in and around their lonely home. Unable to get up and walk – or better yet, run – away from these tragically deluded surrogate parents, he's a prisoner to their unwanted attentions and bizarre emotional demands. All he can do is wait for his body to heal and pray he doesn't incur his new "mother's" festering rage first.

I really liked this movie 16 years ago, when it was called Misery. But back then, it had a few characters in it who weren't complete psychos, which made it a lot easier to figure out who I was supposed to sympathize with, y'know? Also, I remember the supporting roles being filled by professional actors whose line readings didn't in any way suggest that the director had cast his close friends to save a buck. Why, I think the thing even won an Oscar or something.

Ah, good times.

— Steve Schneider

Journey From the Fall

Directed by Ham Tran

6 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Enzian

3:45 p.m. Friday, March 31, at Regal

A sweeping historical tearjerker for fans of To Live and The Blue Kite, Journey From the Fall is an unflinching and true story that tells how Vietnamese citizens' struggles for survival didn't end when the war did. Yet the movie remains accessible in its universal themes of struggle, hope and xenophobia that it will likely receive U.S. distribution.

The film focuses on a family torn apart in the mess of postwar "re-education." In a sometimes confusing narrative that jumps from 1975 to 1979 to 1981 with hardly a warning, we follow Long (Long Nguyen), a soldier who chooses to stay behind and fight for his homeland while organizing a perilous boat trip to America for his mother, wife and son. When Vietnam falls under Communist rule, Long is forced into gruesome slave labor, with any step out of line causing him to be thrown into a Papillon-esque prison box. Years go by as his family attempts a new life in America, wrestling with the false hope of ever seeing him alive again.

Tran Anh Hung's Scent of Green Papaya, Vertical Ray of the Sun and Cyclo – the only Vietnamese films known by most Western cinephiles – never directly addressed the postwar rebuilding of Vietnam, certainly not in the way so many Italian and German films chronicled their country's situations after World War II. So Journey From the Fall, if familiar in its Western-style story arc, is somewhat of a watershed in terms of subject matter. For now, this sensitive and forgiving portrait of a family torn apart is the definitive Vietnam movie from the Vietnamese perspective.

— John Thomason

Kinky Boots

Directed by Julian Jarrold

7 p.m. Friday, March 24, at Enzian

6:30 p.m. Saturday, April 1, at Enzian

Those drag queens, they sure do show us stuffy straight folks how to think outside the wig box. And that's exactly what happens in Kinky Boots, a marginal Britcom in which a failing Northampton shoe factory retains the expert advice of a London trannie (Chiwetel Ejiofor of Dirty Pretty Things) to steer it toward a whole new product category: platform footwear with extra reinforcement for husky cross-dressers. But before that growth market can be tapped, the place has to hit rock bottom thanks to bad accounts and the inexperience of new owner Charlie Price (Joel Edgerton), who's inherited the operation from his deceased dad.

The scenes in which Charlie has to terminate a whole mess of people who are only technically his subordinates represent the film at its most affecting: Talk about an omnipresent aspect of modern-day life that's hardly ever shown on screen. When it comes to identity politics, though, Kinky Boots is about as deep as Mrs. Doubtfire. It's a canny choice for an opening-night film, paying lip service to viewers' "nonconformist" impulses but containing nothing to genuinely offend them – all the way down to a leading man/lady who tosses the word "sex" around like it's his/her last name but shows zero interest in actually having any of the stuff with anybody. The audience will emerge mildly tickled and everybody will have forgotten all about it by the next day, when they start seeking out work of genuine consequence. But first enjoy the hors d'oeuvres.

— Steve Schneider

Lonesome Jim

Directed by Steve Buscemi

9:30 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Enzian

7:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 29, at Regal

Past FFF guest Buscemi scores a wry coup, bringing a hilariously hangdog air to this story of an inveterate loser's homecoming. Poor, luckless Jim (Casey Affleck), his career as a New York City dog-walker in tatters, returns to Goshen, Ind., to enjoy a much-deserved nervous breakdown – but merely succeeds in pushing his older brother (Kevin Corrigan) into a suicidal coma by pointing out that his life is even worse. Looks like Jim will have to stick around awhile, if only to take over for the sidelined Timmy as coach of an inept girl's basketball team. That means daily contact with their surreally cheery mom (Mary Kay Place) and significantly gruffer dad (FFF mainstay Seymour Cassel); for distraction, there's occasional copulation with a nurse (Liv Tyler) who'll agree to put up with Jim's premature-ejaculation problem if he lets her kid tag along on dates.

Affleck makes a perfectly downcast lightning rod for the ennui-ridden goings-on; it's nice to know where the interpretive talent in that family went. As a director, Buscemi totally gets the defeatist beats of writer James C. Strouse's script (the latter's relatives appear in supporting roles, and several scenes were shot at their family factory). Meanwhile, viewers of the "I love that guy!" persuasion will appreciate the casting of hard-working character actor Mark Boone Jr. (Memento, Batman Begins) as Jim's uncle, a proudly degenerate dope dealer who decorates his walls with animal skulls but hopes to add something more human to the mix. Yes, there's one in every family.

— Steve Schneider

Look Both Ways

Directed by Sarah Watt

9:30 p.m. Monday, March 27, at Regal

7:15 p.m. Friday, March 31, at Regal

The plot of Look Both Ways is built upon the most trite conceit in contemporary indie film: The lives of a gaggle of lonely and depressed outsiders are connected by a vehicle crash, their sorrows further linked via montages scored to a Greek chorus of mournful pop songs. But despite the Altman/P.T. Anderson/Paul Haggis/Alejandro González Iñárritu comparisons that description conjures up, this intriguing, freewheeling yarn from Australia bears more resemblance to Atom Egoyan's complex, inquisitive and ever-searching narratives like The Sweet Hereafter and Speaking Parts.

The crash in question is caused by a train, when a man accidentally falls (or, as a hack journalist posits, jumps) in front of it. On the way back from her father's funeral, death-obsessed painter Meryl (Justine Clark) witnesses the accident, and photojournalist Nick (William McInnes), who has just been informed he has testicular cancer, shows up to shoot the scene. The two share constant visions of death – for Meryl, it manifests itself in a series of jarring animated sequences that reflect her internalized paranoia. For Nick, it recurs as he re-evaluates all the potentially cancer-causing things he has done throughout his life, his back story presented in quick, avant-garde snatches.

The film's exciting rumination on the inevitability and omnipresence of death resonates through its peripheral characters as well – the guilt-ridden train driver, the grief-stricken girlfriend of the fallen man, the reporter trying to spin the train story into an exposé about suicide, and his recently pregnant ex-girlfriend, who's contemplating an abortion. In one of Nick's ugly dreams, the cancer he imagines inside him eventually begins to invade the film itself – a scarily intrusive reminder of the innumerable ills of the modern world.

— John Thomason

Matando Cabos

Directed by Alejandro Lozano

10 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal

9:45 p.m. Tuesday, March 28, at Regal

Somehow managing to be both feather-light and inscrutably convoluted, this Mexican film closely mimics the gangsters-as-chatty-fuckups vibe of films like Snatch. Overly silly multiple story lines involving cross-eyed bus drivers, scotched plans and, of course, a washed-up Mexican wrestler (and his ass-kicking midget friend) make for some intriguing potential, but director Lozano puts too much on the screen for any of it to make sense. The dry comedy of the dialogue is constantly at odds with the broad visual humor (remember the ass-kicking midget?), and none of it blends with the dark jokes or the quickly shifting situations.

Although it's great to see a gangster lovingly praise his hard-working father one minute, only to mistakenly kidnap him and shoot him in the foot the next, Lozano drags out that gag for far too long, while other elements of the Byzantine plot remain sadly unexplored. The gritty, urban milieu provides ample opportunities for excitement, but Lozano seems to prefer keeping the drama restricted to small apartments, forcing an unending stream of unlikely characters into these tight environments that could be in Mexico City, Madrid or Muncie.

When the criss-crossing story arcs finally resolve themselves, it's predictably morbid and not without humor. But rather than having a hearty laugh, you're more likely to breathe a sigh of relief that the confusion is finally over. A gangster movie shouldn't be this much work.

— Jason Ferguson

Muskrat Lovely

Directed by Amy Nicholson

9:45 p.m. Thursday, March 30, at Enzian

2 p.m. Saturday, April 1, at Regal

Let nothing prevent you from seeing this documentary.

Dorchester County, Md.'s National Outdoor Show, an annual muskrat-skinning competition, each year also crowns a local high school girl "Miss Outdoors." Director Nicholson has captured this down-home drama with humor, never condescending to her subjects yet reveling in the ooky spectacle of the competition(s). Interviews with each of the eight contestants are interspersed with shots of outdoorsmen slogging through the marsh setting traps, a housewife preparing muskrat casserole, and a park official – holding a stuffed muskrat and strangely reminiscent of Twin Peaks' Log Lady – explaining the significance of the unfortunate animal to the area.

The ghost of Christopher Guest's mockumentaries floats over several scenes, especially a sequence in which a frustrated choreographer attempts to teach a 12-minute "musical routine" to the eight girls, a lumpen if good-natured lot. In another series of shots, the heavyset pageant director earnestly explains the history of the handed-down Miss Outdoors tiara while absently picking stray hairs off the rhinestone behemoth. (Guest's actors could only dream of coming up with a bit of business like that.)

The contrast between the bloody piles of fur and meat and the heavily Maybellined-and-hairsprayed girls at the show is comical, but Muskrat Lovely is never patronizing. The contestants are all bright and well-spoken (until they're onstage, anyway), and there's none of the backstage backstabbing that inevitably figures in any fictional account of beauty pageants. If this cross between Waiting for Guffman and Miss Congeniality has any flaw, it is its too-symmetrical structure, but any niggling complaint is overshadowed by the sheer comedic value of the looks on the judges' faces during the talent portion of the pageant. Corky St. Clair, eat your heart out.

— Jessica Bryce Young

Press On

Directed by Gillian Grisman

9:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 29, at Regal

1:30 p.m. Saturday, April 1, at Regal

This documentary telling of Robert Randolph's musical ascendance from obscurity and provincial social ills could easily have been bungled. The opening dialogue hints at an hour-plus of white-centric relief that a young African-American made it to the media mainstream without channeling the well-worn and -marketed path of rap music. Thankfully, a better story is told here: will to power matched with some managerial cunning to sell a young church pedal-steel guitarist to a stratum of tastemakers. (Never before has a bluesman's trip to the crossroads been captured as well as when we see Randolph perform a showcase at the Warner Bros. Records headquarters.)

Press On starts by being studiously reverent to the roots of Randolph's steel playing as an anointed voice in a House of God church. The sound of the steel is an ecstatic howl of wordless melodic praise, with a decibel level you'd reserve for a rock band. As if he sees the subject's past, present and future, Eric Clapton sagely hints at this critical component that affords Robert Randolph and his Family Band their meteoric access to opening slots with arena- and stadium-level musicians – and later, a Grammy performance. Everyone along the way seems floored by the temerity Randolph employs to transform the status of a peripheral instrument. But would a six-string-guitar-playing Robert get to jam with the A-list? The film blunts that cynicism by revealing an infectious joie de vivre transplanted from the church aisle to secular concert venues. Ultimately, you just have to submit.

— Matt Gorney

The Puffy Chair

Directed by Jay Duplass

10 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Enzian

3:30 p.m. Thursday, March 30, at Regal

Seconds into the Duplass brothers' Gen-Y dramedy, you realize: I know these people. As they face each other across their humble kitchen table, lovebirds Emily (Kathryn Aselton) and Josh (Mark Duplass, also the film's writer) affect goofy grins and coo sweet nothings to each other with Hallmark-skewering delight; they're ostensibly intelligent people who talk like microcephalic pinheads because they think it's cute. Later, they will refer to their moments of romantic indulgence as "schmoopy time."

When she's not making goo-goo eyes at Josh, though, Emily is pitching his dinner all over the floor. Real, adult tension underlies their relationship, and it's only slightly mitigated when he agrees to take her along on a road trip from New York to Atlanta. (Purpose of the jaunt: to pick up a red recliner and deliver it to Josh's dad as a birthday present.) Complicating matters even further is the presence of Josh's brother, Rhett (Rhett Wilkins), a well-meaning hanger-on with a Cat Stevens beard and a personality as annoyingly benign as, well, a Cat Stevens lyric.

Out on the road, everything happens and nothing happens, which is the way life is for folks like these. Mark Duplass nails their milieu, both as a writer and a performer (he resembles a young Dennis Quaid who can nonetheless act), and brother Jay's direction captures the emotional ill-preparedness of a generation trapped inside irony. (Josh addresses Emily as "dude," and he's only kidding half the time.) The filmmakers concoct some frighteningly realistic arguments, and even reach for the vérité stars by attempting a climax that's fearlessly downbeat. It doesn't work – but then again, neither do plenty of relationships. "Schmoopy time," as we all know, is easier said than secured.

— Steve Schneider

Purvis of Overtown

Directed by Shaun Conrad and David Raccuglia

6:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 29, at Regal

4:30 p.m. Saturday, April 1, at Regal

Beauty cuts deep in this splendid documentary about venerable, from-the-streets folk artist Purvis Young, who has lived his entire life in Miami's Overtown black ghetto, where he was born in 1943. His works, Young says, are a reflection of what he sees in his everyday life in the poverty-stricken, drug-infested neighborhood; if there were peace in the world, he'd put down his brush. Young's works are in major art collections around the world, even in the Smithsonian. But he's still just Mr. Young to the kids who see him bicycling around his home turf.

The filmmakers must be credited for the aesthetics that imbue the collage of interviews with art collectors, historians and Overtown residents – material blended with historical footage and, best of all, treasurable talk by the aging folk hero himself. Young, a man of faith, discusses his youth and his time spent in prison, where he claims to have been visited by the angels that guided his artistic visions. And that's where the distinctive quality of his style comes into play. No matter how depressing the subject matter – which is all grounded in racism – the depiction is washed in hope.

Young transforms the despair of life in the ghetto into something uplifting; the filmmaking team of Conrad and Raccuglia has emulated that transcendence in their film. An original music score by Otis Wells soundtracks the celebration, even as the story turns into one of exploitation and greed.

— Lindy T. Shepherd

Revolution '67

Directed by Marylou Tibaldo-Bongiorno

2:45 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal

6:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 28, at Enzian

On the West Coast of the United States, July 1967 was the height of the so-called Summer of Love. But back east, the failing New Jersey city of Newark was exploding in one of the most notorious riots of a turbulent decade.

Or was it a riot? Even that terminology is up for debate in the relentlessly inquisitive documentary Revolution '67, which holds that Newark actually experienced a "rebellion" brought about by years of race-based injustice and neglect. Relying on the testimony of those who were there (from government peacekeepers to student-turned-community activist Tom Hayden), the movie assembles an urban timeline that picks up roughly about the time Newark's whites fled to the suburbs, leaving their darker neighbors to inherit a crumbling infrastructure and wholesale corruption. When a black taxi driver was beaten by police, a rumor went out that he had died – and the fed-up populace mounted an uprising that quickly escalated beyond its control, thanks to paranoid, heavily armed National Guardsmen and nonexistent coordination between law-enforcement agencies.

Digging deeper than most docs, the film argues that the rioters – excuse me, rebels – had been disenfranchised by a systematic campaign of economic subjugation. The film's reformist zeal once or twice overtakes its storytelling, and a final, tossed-off mention that the city was able to remake itself many decades later begs greater explanation – how, exactly? But it's the mark of a superb festival doc that, after a comparatively lengthy 90 minutes, you still wish there were more.

— Steve Schneider

Runaway

Directed by Tim McCann

2:45 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

9:15 p.m. Tuesday, March 28, at Regal

Director McCann's Revolution #9 (FFF 2002) was a disturbingly realistic account of mental illness in the guise of a paranoid conspiracy film. The challenging Runaway, too, deals with a protagonist who has trouble functioning in society, and the movie similarly concludes with a depressing hoodwink that gives its final stanza more meaning than the rest of it combined.

The film is a succession of two fractured slow builds that lead to a shattering climax. In one, we encounter 21-year-old Michael (Aaron Stanford, Tadpole), a runaway living in a dingy motel room with his 6-year-old brother Dylan. He works the graveyard shift in a convenience store and occasionally writes letters to a therapist (Terry Kinney). In the parallel story, we see a younger, suicidal Michael talking to the therapist in person and being reduced to virtual slavery by his domineering parents. As both narratives progress, we gradually get the clear impetus for his mysterious escape from home.

Just as Revolution #9 faked being a thriller before playing its hand, Runaway's revelation is masked by a budding romance between Michael and Carly (an exceptional Robin Tunney), a 27-year-old high school dropout working at the same store and trying to earn her GED. Michael's care and love for Carly and Dylan make for poignant moments in a film that is otherwise profoundly unpleasant. Runaway is not for the squeamish, but it's an important step toward freeing schizophrenic cinema from A Beautiful Mind-style Hollywood mythologizing.

— John Thomason

Salvage

Directed by Joshua and Jeffrey Crook

Midnight Saturday, March 25, at Regal

9:45 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

Devotees of horror hold a certain tolerance for low-budget production values, particularly when a movie's ideas and images are compelling enough. Salvage attempts to tell an interesting, if somewhat derivative story, yet is continually thwarted by its hit-or-miss quality.

Claire Parker (Lauren Currie Lewis) catches a ride home with Duke (Chris Ferry, also one of the film's producers), who is mysteriously driving her boyfriend's truck. Once home, Duke attacks Claire, drags her into the basement and murders her. And then Claire wakes up, apparently having daydreamed the entire incident. But scenes and elements from these visions keep reappearing as Claire relives her own murder again and again – each time trying to escape, and each time ending up inexplicably back in the same horrific situations.

Salvage looks pretty good given its obvious budget constraints: Shot on video, it contains some scenes that are extremely well-done, with great attention paid to post-production; others, though, look as if they were shot on a VHS camcorder. (While some of the images are quite violent, most of the gore is left off-screen.) Inconsistency plagues the audio as well, with some scenes scored to perfection and others marred by tragic soundtrack selections or spotty location sound.

To cut this 82-minute feature down to an hour wouldn't hurt the story at all, and would eliminate most of the inconsistencies. The performances are above average and the story is interesting. It's too bad the technical problems prevent the suspension of disbelief needed to make it work.

— Ian Monroe

Showbusiness: A Season to Remember

Directed by Dori Berinstein

3:15 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Enzian

9 p.m. Wednesday, March 29, at Regal

Earning the Tony Award for best musical is like winning the Super Bowl to kids who were too asthmatic to play sports. But the year-in-the-life documentary Showbusiness does more than dither over which high-profile show will be named 2004's top dog: It paints a portrait of a theatrical season in which four debuting musicals have to overcome serious challenges – some artistic, most commercial – to find and hold an audience.

The revisionist Oz prequel Wicked gets a major overhaul after its unspectacular San Francisco tryout, only to garner lukewarm reviews from the New York critics; similarly, the British import Taboo is buffeted by gossip-page reports of tension between principals Boy George and Rosie O'Donnell. Downtown puppet-palooza Avenue Q comes to Broadway accompanied by anxieties that it skews too young, while Tony Kushner's Caroline, or Change takes the biggest risk of all, employing serious themes and textual intelligence to stand out from the surrounding Webber-isms.

This compelling doc spends an immense amount of quality time with the creative principals behind all four shows. As a bunch, they're more colorful than diverse: It takes the movie just minutes to reach what Cartman once termed (ahem!) Fag Factor Five. Yet even viewers who find the song-in-my-heart backstage testimonials faintly ludicrous may sweat off an ounce or two wondering which show(s) will survive long enough to dominate on Tony night – and which luckless librettists will have to go home and bite their pillows instead. Also of note is the deliciously unflattering portrayal of the theater press, who (save The New Yorker's John Lahr) come off as underqualified, congenitally cowardly rumor-mongers unable to divine the tastes of the readership they purport to serve. Hey, good call!

— Steve Schneider

So Much So Fast

Directed by Steven Ascher and Jeanne Jordan

4:45 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Enzian

1:30 p.m. Friday, March 31, at Regal

There's an archival clip from a 60 Minutes telecast early on in So Much So Fast, a film that feels like an 87-minute version of CBS' weekly newsmagazine if it were granted a more poetic visual license. A fascinating and tragic piece of investigative journalism, the movie tackles the devastating disease ALS, or Lou Gehrig's Disease, which gradually erodes the nervous and muscular systems.

Stephen Heywood is the illness' human face – a buoyant young man with a zeal for architecture, video games and life. At the turn of this century, Stephen became one of the thousands of people a year diagnosed with ALS. Medical science has all but given up on finding a cure, but that doesn't stop Stephen's brother Jamie from forming the ALS Therapy Development Foundation and devoting his life to curing the disease before Stephen's expected five-year lifespan dissipates.

So Much So Fast is not without humor, and the filmmakers couldn't have picked a more upbeat victim than Stephen. His sarcasm and pragmatism keep the film from veering into teary sentimentality, while Ascher's camera work probes every pore of Stephen's face without preaching to the audience.

But as the film's title indicates, this wake-up call about the significance of ALS presents a race against a clock that can stop at any moment. The passage of time is palpable as Ascher and Jordan document both Jamie's struggle to lengthen his brother's life and Stephen's crushing deterioration. The film is at once an exposé about coping with ALS and a tension-filled find-the-cure drama, with love for and dedication to family transcending the bleakness.

— John Thomason

Steal Me

Directed by Melissa Painter

6 p.m. Saturday, March 25, at Regal

1:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 29, at Enzian

Kleptomaniacs and nymphomaniacs: a lot more common in the movies than they are in real life, aren't they? Steal Me unfolds a story about the collision of a homeless teen with a happy family, digging deep into the metaphorical implications of theft. Fifteen-year-old Jake (Danny Alexander), our larcenous Romeo, is hopping trains and stealing for a living while searching for his feckless mother, who has abandoned him. Through a series of implausible events he winds up living with Tucker, a Montana teenager, and his family. Adroit both at breaking and entering and at insinuating himself into others' affections (that thud you heard was the screenplay hitting you over the head), Jake is soon sleeping with the earthy next-door neighbor and coaching mama's boy Tucker how to hook up with the town wild child, Lily Rose (Paz de la Huerta as a slangy, bare-midriffed Lolita).

Despite the sometimes contrived plot, Steal Me is worth seeing; it's worth overlooking the shortcomings just to catch Cara Seymour's (Dancer in the Dark, Adaptation) deeply intelligent characterization of Tucker's unsentimental mother. Painter's film is rife with sexual undercurrents, exploring the half-hidden erotic elements in every relationship: teen boys wrestling and talking smack, the crush of a 9-year-old girl on her big brother's friend, the physicality of the maternal bond, the maternal component that steals into an older-woman/younger-man relationship. Probing the emotional symbolism of theft is not an especially original concept, but Steal Me, as pretty and awkward as a teenager, has an easy appeal.

— Jessica Bryce Young

Sweet Land

Directed by Ali Selim

2:15 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Regal

6:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 28, at Regal

What we have here is an otherwise respectable period drama that keeps descending to an after-school special level of bluntness. Hating people for their nationality is really bad, see, which the unnecessarily earnest Sweet Land reminds us by having its cast of 1920s Midwesterners castigate a German Socialist immigrant (Elizabeth Reaser) with sputtered variations on the phrase, "She's different from us!" Most of the time, something far subtler would suffice. (A pained expression, even.)

Reaser comes out best, in part because she's a terrific face actress and also because her role as a non-English-speaking mail-order bride indemnifies her against the movie's clunkier dialogue. Her Inge Ottenberg travels to Minnesota to marry a Norwegian farmer, only to come smack-dab against a set of nasty prejudices. Though there was certainly anti-German sentiment in the Midwest, the severity of the scenario is a tad suspect; the movie's biggest claims to authenticity are its terrific art direction and costuming, which soundly reinforce the '20s passages and a few scenes set four decades later, with Lois Smith (Minority Report) playing the now-aged Inge. (Check out the note-perfect styling of Smith's black funeral dress, and of her substitute-teacher eyeglasses.)

In a weird reversal of the usual festival modus operandi, the better-known actors give the worst performances: Ned Beatty does a lot of harrumphing as a greedy banker, and Alan Cumming (one of the film's producers) almost pulls down the entire house of cards with his appearances as a Minnesotan farmer who inexplicably cavorts about the screen with the unbridled animation of Pee-wee Herman. He seems to have dropped in from another film altogether, and you wish he would drop right back.

— Steve Schneider

The Trials of Darryl Hunt

Directed by Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg

6:30 p.m. Monday, March 27, at Regal

4 p.m. Thursday, March 30, at Regal

A white woman is brutally raped and murdered in the South. A black man is charged with the crime. Justice is not served. You already know this story, even if you aren't familiar with the particulars of this case.

What you don't know is how extensively the court system of North Carolina will twist itself into knots to keep an innocent man in prison. First came the case police in Winston-Salem originally built against Darryl Hunt as Deborah Sykes' killer, which was negligent at best and criminally biased at worst. Then came Hunt's trials, which featured a 14-year-old, drug-addicted prostitute with a lying problem and a Klansman who picked the wrong man out of a lineup – twice – as star witnesses for the prosecution. When DNA evidence later proved Hunt wasn't Sykes' rapist, the state still wouldn't let him out of prison because he might have been involved in the crime in some other way. Appeals all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court went nowhere.

Hunt spent 20 years in prison, and would have rotted there for life had a newspaper reporter not made an obvious link the cops either overlooked or covered up. He was exonerated in 2004.

Filmmakers Stern and Sundberg spent a decade following the case, meaning they got involved when there was little hope Hunt would ever be free again. The resulting documentary is a stinging indictment of institutional racism that's almost too hard to watch.

— Bob Whitby

Wide Awake

Directed by Alan Berliner

7:30 p.m. Sunday, March 26, at Enzian

4:15 p.m. Friday, March 31, at Regal

The debate rages as to whether Alan Berliner's work is merely egoistic or full-on egotistic, but who cares when he keeps turning out documentaries as enjoyably kinetic as Wide Awake? Having reveled in purposeful navel-gazing with films about his immediate family (Intimate Stranger, Nobody's Business) and his own name (The Sweetest Sound), Berliner locates his latest subject in one of his most enduring afflictions: insomnia.

He's been a sufferer for almost all of his 48 years, he tells us, then proves it with a gleefully masochistic fun-house ride through the remote corners of his sleep-deprived mind. A night-vision camera records the tossing and turning that is his pre-dawn ritual, and visits to a battery of medical professionals expose the limited effectiveness of old-fashioned remedies like counting sheep. (Practically immune to relaxation, Berliner has to give up and stop counting after a few hundred imaginary animals have hopped the fence.)

Yet if the project is unabashedly self-serving, it's kept universal by Berliner's obsessive scholarship – when he's in the thick of an experience, he wants to know its history inside and out – and masterful wielding of kitschy archival footage. Fast-paced and expertly edited, the movie fixes Berliner among an elite group of documentarians (Kate Davis and Michael Moore among them) who understand entertainment better than most of their contemporaries working in narrative features. Wide Awake doesn't find a cure for insomnia, but it's practically an antidote to narcolepsy: You'll be at rapt attention from the first frame to the last.

— Steve Schneider

Wordplay

Directed by Patrick Creadon

7:15 p.m. Thursday, March 30, at Enzian

5 p.m. Sunday, April 2, at Regal

If you loved Spellbound and Word Wars (FFF 2004), you're in the viewership demo for Wordplay, yet another doc in which lovable brainiacs go head-to-head to prove who has the bigger vocabulary. Though the allure of undiscovered territory is thus absent from director Creadon's record of the 2005 American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, his treatment of the material is enthusiastic and well-structured enough to save this frequently exhilarating film from redundancy.

We learn the mild quirks of the featured competitors, who converge on a Connecticut hotel to fill in little squares as fast as their pencils will allow. But on a larger scale, the movie honors a hobby that enlivens the daily routines of countless Americans. Their guru is Will Shortz, editor of the prestigious New York Times puzzle and founder of the 17-year-old tournament; dancing to his etymological tune is a nation of hard-core puzzle junkies, including celebrities like Jon Stewart and Bill Clinton. Stewart is seen scribbling his way through a crossword with comic bravado ("Bring it," he entreats the absent Shortz), while the interviews with the ex-president reassure us that there was once somebody in the Oval Office who knew his way around a brainteaser, much less a writing utensil.

While lacking the socioeconomic significance of Spellbound (the key players in the climactic tournament are overwhelmingly white

[email protected]